Mana Makani: The Power of the Wind

Credit: Katherine (Loke) Roseguo, Anela

Benson

Grade Level: 6-8

Learning Time: 1week

Keywords: wind, meteorology, Hadley cell,

Coriolis effect, the Wind Gourd of La‘amaomao,

voyaging

(Photo source: K. Roseguo)

Summary & Goals:

Students continue to develop their skills in observation by noting the various attributes of global

and local winds. This lesson seeks to clarify the origin of “trade winds” and the seasonal changes

that affect atmospheric circulation most proximal to the Hawaiian Archipelago.

Background | Standards | Resources and Materials | Instructions | References

Background:

SCIENTIFIC

Meteorology is the scientific study of Earth’s atmosphere (the layer of gases that

surrounds Earth and is held in place by its gravity), which protects Earth’s life forms by

absorbing ultraviolet solar radiation, warming Earth’s surface through heat retention, and

regulating temperature extremes between day and night. The troposphere is both the largest

(in terms of volume) and lowest (in terms of altitude) portion of Earth’s atmosphere,

comprising about 80% of its mass and extending to an average maximum height of about 11

miles above Earth’s surface. Within the troposphere, global wind (the flow of gases on a

large scale) is caused by differential heating between the equator and the poles (i.e., the

difference in absorption of solar energy, with the equator absorbing more and the poles less)

as well as by the Earth’s rotation. In general, heat is transferred through three processes:

Conduction (between two objects making physical contact),

Convection (between an object and its environment), and/or

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

1

Radiation (to or from a body through emission or absorption of electromagnetic

radiation).

When there is a difference in atmospheric pressure on the earth’s surface, air moves from

higher-pressure areas (e.g., the Tropic of Cancer or Capricorn) to lower pressure areas (e.g.,

the equator or the poles) and results in winds of various speeds. The heated, rising air then

redistributes heat from the equator to the north and south poles. If this heat were not

distributed by winds, the equatorial regions would heat continuously while the Polar Regions

would cool continuously.

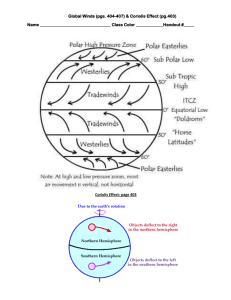

Trade winds are caused in part by the

descending (i.e., moving from north to

south as well as from higher to lower

altitude) cool air of a Hadley cell, which

is part of a three-cell model that explains

the general nature of atmospheric

circulation. Hadley cells extend from

the equator until the Tropic of Cancer

(30-degree north latitude) within the

northern hemisphere and from the

equator until the Tropic of Capricorn

(30-degree south latitude) within the

southern hemisphere. However, contrary

to normal intuition, wind currents do not

travel in straight lines. Due to the

Earth’s rotation, the wind appears to

bend either to the left or to the right,

depending on which hemisphere the

observer is in -- this is the Coriolis effect. A person standing on the equator actually moves

faster than another standing at the poles due to conservation of angular momentum.

Therefore, if an observer at the North Pole were to toss a ball to a person on the equator, the

ball would appear to deflect to the right of that person because they would have moved past

the location on earth where that ball would have arrived. Honolulu has a latitude of 21

degrees north (of the equator) and, therefore, is south of the descending branch of the Hadley

cell (located at the latitude of 30 north), which creates surface winds or Trade Winds that

blow from the NE throughout the year.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

2

General Wind Patterns of the Pacific during Trade Wind Season

(Irwin, 2006, p. 70)

On a more local scale, sea breezes (the shoreward movement of air) form when nearby

land heats up during the day, its’ warm air rises only to be replaced by cooler air from over

the water, creeping in at about noon, becoming strongest by late afternoon, and then tapering

off, only to die at around sunset (Seidman, 1995, p. 15). At night, as the land rapidly cools,

the air above it becomes comparatively colder than the air over its surrounding water (whose

temperature is more stable), causing a wind to blow from the land toward the water and

forming a land breeze (p. 15). Sea and land breezes may work with or against a prevailing

wind.

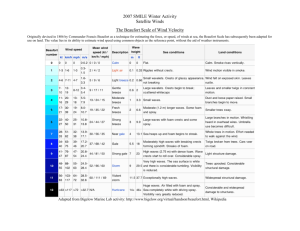

In meteorology, winds are classified by their strength and the direction from which they

blow. The nautical term knot (nautical miles per hour) is used to describe the speed or

strength of the wind, where 1 knot = 1.15 [statute or “land”] miles per hour (Fries, 1997, p.

22), and the direction from (not to) which the wind is blowing is the designated direction of

the wind (p. 21). The Beaufort wind force scale (or simply the Beaufort scale), devised in

1805 by Irish Royal Navy officer Francis Beaufort, is an empirical measure that relates wind

speed to observed conditions at sea or on land, assigning each a “Beaufort number”:

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

3

Beaufort Scale: Specifications and Equivalent Speeds for Use on Land

(No author, 2010)

CULTURAL

While the term “trade winds” was created by European sailors who found the winds

favorable for their trading expeditions, the Hawaiian system of naming winds was placebased, resulting in many different names for trade winds across the islands. One common

name was A‘e, which can also mean diagonal. Variations on this name include A‘e Loa,

Moa‘e, Moa‘e Kū, Moa‘e Pehu, and Na‘e. The more general description nā makani mau

(regular winds) might also be used to refer to trade winds, depending on one’s location.

According to revered Hawaiian historian David Malo (1951),

Wind always produced a coolness in the air. There was the kona, a wind from the

south, of great violence and of wide extent. It affected all sides of an island, east, west,

north and south, and continued for many days. It was felt as a gentle wind on the

koolau—the north-eastern or trade-wind—side of an island, but violent and tempestuous

on the southern coast, or the front of the islands (kea lo o na mokupuni). The kona wind

often brings rain, though sometimes it is rainless. […] The kona-ku is accompanied with

an abundance of rain; but the kona-mae, the withering kona, is a cold wind. The konalani brings slight showers; the kona-hea is a cold storm; and the kona-hili-maia—the

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

4

banana-thrashing kona—blows directly from the mountains. The hoolua, a wind that

blows from the north, sometimes brings rain and sometimes is rainless. The hau is a

wind from the mountains, and they are thought to be the cause of it, because this wind

invariably blows from the mountains outwards towards the circumference of the island.

There is a wind which blows from the sea, and is thought to be the current of the land

breeze returning again to the mountains. This wind blows only on the leeward exposure,

or front (alo) of an island. In some parts this wind is named eka (a name used in Kona,

Hawaii), in others aa (a name used at Lahaina and elsewhere), in others kai-a-ulu, and in

others still inu-wai. There was a great variety of names applied to the winds by the

ancients as the people saw fit to name them in different places. (p. 14)

Nā Kūkulu [Cardinal Directions] & Nā Makani [Winds]

(Alameida, 1997)

One of the most valuable resources for traditional Hawaiian wind names is the Wind

Gourd of La‘amaomao, a story about a boy named Pāka‘a, whose mother gives him a gourd

that contains the bones of his grandmother La‘amaomao. With this gourd and the chants of

wind names that his mother teaches him, Pāka‘a is able to control the winds.

Within the Hawaiian pae ʻāina (archipelago), Moloka‘i is considered to be the island of

the winds. This is partly due to its mountains affecting winds far less than those of any other

island: the winds can pass easily over the lowest parts of Molokaʻi without having to split or

even rise very far. The western half of Moloka‘i is dry because it lacks orographic rainfall.

Orographic rainfall occurs when an air mass is pushed against a boundary such as the

Koʻolau Mountains by prevailing winds -- to pass over the mountains, the air mass rises and

cools simultaneously. As the air mass cools, water molecules begin to coalesce in to larger

droplets and moisture in the form of rain is released allowing the cloud to rise over the

mountains. The forced ascent by terrain is the reason why the windward sides of all the

Hawaiian Islands are lush and green with vegetation. Conversely, air that has already lost

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

5

much of its moisture becomes even drier as it descends and warms along the lee slopes,

making lee areas of all the islands relatively dry. The exception is the Kona coast of the

Island of Hawai‘i, where the trade winds are blocked by Mauna Loa, and a well-developed

(and almost daily) sea breeze brings clouds and rainfall upslope.

VOYAGING

Biodiversity and early oceanic explorations in the Pacific depended closely on the regular

wind patterns, since wind was their main source of transportation (i.e., by wind, wave, or

wing) and/or power (i.e., by sailing). Tahitian navigators divided the horizon into bearings

denominated by distinctive wind blowing from various points.

Tahitian Wind Compass (Finney & Low, 2006, p. 162)

Other Oceanic peoples (including Hawaiians) employed wind gourds. In the Cook

Islands, such a wind gourd might have holes drilled around its perimeter, representing the rua

matangi (i.e., wind pits) through which the named winds would blow. Each hole was

stopped up with a twisted piece of tapa that would be removed in order to provide a “gentle

hint” to Raka (the god of the winds) as to the direction from which steady winds would be

most desirable for a voyage. In contrast, although the star compass of Hawaiian pwo (master

navigator) Nainoa Thompson (http://pvs.kcc.hawaii.edu/ike/hookele/star_compasses.html)

names only four predominant winds (i.e., Koʻolau, Malanai, Kona, and Hoʻolua), these wind

names represent whole quadrants of the compass and are used more to distinguish between

similarly named houses in opposite directions. In addition, like the movement of swells,

winds are envisioned as straights lines crossing through or beneath the observer (onboard the

waʻa or canoe) from one directional house into a house of the same name but within the

diagonally opposite quadrant. For example, wind approaching the waʻa from Nālani Koʻolau

(NE) will continue heading towards Nālani Kona (SW).

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

6

Cook Islands Wind Compass (Finney & Low, 2006, p. 163)

In order to sail, one must observe and know the direction and strength of the wind: when

the pressure of the wind is even on both cheeks and ears, one is directly facing the wind.

One can tell wind direction also by watching the direction in which the clouds are moving or

the ripples on the ocean are running. Also, when aboard a moving vessel at sea, the true

wind is different from the apparent wind (i.e., the wind that you feel), which is a

combination of the true wind plus the wind your vessel is creating by moving. In any case,

one must be able to actually observe the sea (or get a report from a vessel or buoy at sea) in

order to get an accurate reading of conditions at sea.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

7

Beaufort Scale: Specifications and Equivalent Speeds for Use at Sea

(No author, 2010)

The channels between the Hawaiian Islands are sometimes dangerous for navigating,

because the trade winds are funneled through the narrow areas between islands, causing the

pressure gradient to increase between the entrance and exit of the channel and, in turn,

causing the wind speed to increase. The waves generated by these higher winds can interact

with ambient swells, particularly those coming up from the south, to produce very steep

standing waves. This is why many boating accidents occur in the island channels.

BISHOP MUSEUM

The Wind Gourd of Laʻamaomao was passed down and eventually presented as a gift to

King David Kalākaua, and a gourd of the same name and reputation is currently housed

within Bishop Museum’s Cultural Collections

(http://www.bishopmuseum.org/research/cultstud/cultstud.html).

The museum also offers the Science on a Sphere (SOS) program “Under the Weather,”

which explores the relationship between the Sun, the Earth’s tilt, the oceans, and Hawaiʻi’s

seasonal weather (while addressing 8th Grade HCPS III Benchmarks SC.8.8.3, SC.8.8.4, &

SC.8.8.7) using satellite and other data projected onto a 6-foot diameter globe.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

8

(http://www.bishopmuseum.org/education/science_programs.html).

Back to top

Standards:

Nā Honua Mauli Ola

‘Ike Lāhui (Cultural Identity Pathway)

‘Ike ʻŌlelo (Language Pathway)

‘Ike Honua (Sense of Place Pathway)

GLOs

GLO 3: Complex Thinker: 3.2- Considers multiple perspectives; 3.3-Generates new and

creative ideas and approaches

GLO5: Effective communicator: 5.1 Listens to, interprets, and uses information effectively;

5.3 Reads with understanding various types of written materials and literature and uses

information for various purposes; 5.4 Communicates effectively and clearly through writing;

5.5 Observes and makes sense of visual information

HCPS III

Grades 6 - 8 Science, Earth/Space Science

SC.6.1.2 Use appropriate tools, equipment, and techniques safely to collect, display, and

analyze data.

SC.6.3.1 Describe how matter and energy are transferred within and among living systems

and their physical environment.

SC.6.6.3 Explain how energy can change forms and is conserved.

SC.7.2.1 Understand that science, technology, and society are interrelated.

SC.8.2.1 Describe significant relationships among society, science, and technology and how

one impacts the other.

SC.8.8.3 Describe how the Earth’s motions and tilt on its axis affect the seasons and weather

patterns.

SC.8.8.4 Explain how the sun is the major source of energy influencing climate and weather

on Earth.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

9

SC.8.8.6 Explain the relationship between density and convection currents in the ocean and

atmosphere.

SC.ES.8.1 Describe how elements and water move through the oceans, atmosphere, and

living things as part of geochemical cycles.

SC.ES.8.4 Describe how heat and energy transfer into and out of the atmosphere and their

involvement in global climate.

SC.ES.8.6 Describe how winds and ocean currents are produced on the Earth’s surface.

SC.ES.8.7 Describe climate and weather patterns associated with certain geographic

locations and features.

Common Core

Grades 6-8 Reading Literacy Science & Technical

6-8.RST.9: Compare and contrast information gained from experiments, simulations, video,

or multimedia sources with that gained from reading a text.

Grades 6-8 Writing

6-8.W.1: Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence.

6-8.W.2: Write informative/explanatory text to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts,

and information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content.

6-8.W.7: Conduct short research projects to answer a question, drawing on several sources

and refocusing the inquiry when appropriate.

Grades 6-8 Speaking/Listening

6-8.SL.2: Interpret information presented in diverse media and formats and explain how it

contributes to a topic, text, or issue under study.

NGSS

Middle School Weather and Climate

MS-ESS2.D: Weather and Climate

Middle School Energy

MS-PS3.A: Definitions of energy

MS-ETS1.A: Defining and delimiting an engineering problem (criteria and constraints)

Back to top

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

10

Resources and Materials:

Books & Reading Materials

Nakuina, M. K. (2005). The Wind Gourd of Laʻamaomao (Rev. ed.). (E. T. Mookini & S.

Nākoa, Trans.). Honolulu, HI: Kalamakū Press.

Pukui, M. K. (1983). ʻŌlelo noʻeau: Hawaiian proverbs & poetical sayings. Honolulu,

HI: Bishop Museum Press. (ʻŌ.N. #s 1455-1469)

Demonstration Materials

5.5 gal glass fish tank

newspaper

matches

ice

plastic container (to contain ice in a trough)

sheet of glass (larger than surface area of fish tank to utilize as a lid)

safety goggles

fire extinguisher

Materials

Notebooks

Pencils

Digital Wind Speed Gauge Anemometer & Thermometers (cheapest = $20:

o http://www.meritline.com/digital-wind-speed-scale-gauge-anemometer-thermometer--p-78783.aspx?source=fghdac&gclid=CI2lmf6WrLkCFQ9dQgodh0wACA)

Websites

Conduction, Convection, and Radiation song/rap:

o http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Y3mfAGVn1c

How to Build an Imu:

o http://hawaiianseamonkey.com/2010/10/how-to-build-an-imu-hawaiian-Earthenoven/

Back to top

Instructional Procedures:

1. ENGAGE:

Ask students to make observations about the clouds in the following aerial

photograph of a portion of the Hawaiian Islands (taken from a NASA space station).

o What is pictured?

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

11

o Where are we?

o What can you tell about the wind (in terms of its direction of origin) by looking at

the clouds in this picture?

o Which side of the island probably has the strongest winds? The gentlest winds?

Why?

(Photo source: NASA)

Demonstrate how convection occurs within a Hadley Cell. Remember to discuss the

formation of low and high pressures within the box. On the ‘Hot’ side of the box, as

warm air molecules rise, a low pressure develops below and a high pressure develops

above. Conversely, on the ‘Cool’ side of the box, the cold air molecules sink,

accordingly a high pressure develops below, and a low pressure develops above.

Thus, as the heating and cooling affect continues, and areas of high pressure move to

areas of low pressure, a convection cell begins to form.

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

Set a 5.5 gal tank on a firm and level surface in a room/area with decent

ventilation.

Set approximately 2 cups of ice in a shallow tray on one side of the tank. (*Note:

Ice should be stacked significantly higher than tray to allow horizontal flow of

cool air during the warm air displacement. Furthermore, allow the ice to sit in the

tank for at least 10 min to allow the surrounding air to cool significantly to create

a decent temperature gradient.)

Take a sheet of newspaper, and crumple it into a loosely packed ball (to allow

better air circulation and surface area exposure for a quick-burning fire).

Light a match, and then ignite the ball of newspaper on fire on the opposite side

of the tank.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

12

v.

vi.

vii.

Allow newspaper to completely burn and smolder, releasing most of the smoke

before covering the tank with the sheet of glass.

As the smoke turns from black and grey to white, cover the tank with the sheet of

glass. Within a few seconds of covering the lid, students should be able to observe

the convection cell circulating within the tank.

Allow students to record their observations, noting the convection cell generated

as the hot smoke rising from the embers of the newspaper are displaced by cool

air from the ice on the other end of the tank.

2. EXPLORE:

Have the students spend a few minutes outside making observations about the

direction from which the wind comes, using their various senses, the Beaufort scale,

and anemometers to collect data.

o Sight: How does the wind look? Can you see the effects of the wind? (e.g.,

swaying trees, moving clouds, ripples on water);

o Hearing: How does the wind sound? Does the sound vary?

o Touching: How does the wind feel? Is it warm or cold?

o Smelling: How does the wind smell?

3. EXPLAIN:

Divide the students into 4 or 5 groups.

Give each group a list of the winds (from the translation of the The Wind Gourd of

Laʻamaomao): Hawaiʻi (pp. 39-42), Oʻahu (pp. 42-44), Kauaʻi (pp. 45-47), and Maui

& Molokaʻi (pp. 54-59).

Have them look up related ʻōlelo noʻeau for the winds of their assigned island as well

as read David Malo’s excerpt on winds.

Giving them blank outlines of Hawaiʻi, Oʻahu, Kauaʻi, and Maui and Molokaʻi, have

the students write the names of the winds where they belong on (or relative to) each

island and the ʻōlelo noʻeau that relate to them.

Have the students compare the name(s) of the wind in your school’s ahupuaʻa with

their actual observations from outside.

o Have the winds changed or stayed the same since they were originally named?

o What other winds throughout the archipelago might resemble the wind(s) of your

ahupuaʻa

4. ELABORATE/EXTEND:

Play the “Conduction, Convection, and Radiation song/rap” for the students, followed

by having them read and take notes on the process of building (and using) an imu (a

Hawaiian earthen oven). Next, as a class, visit and help with the preparation of an

imu, either at your school (if your school has the facilities) or within the neighboring

community. After enjoying the food produced, have students illustrate the various

heating processes at work and relate what occurs inside the imu to what happens to

air within the atmosphere to create wind.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

13

5. EVALUATE:

Using an evaluation template provided by the teacher, students will reflect on and

assess the quality and completeness of their own and their classmates’ notes and

observations (from the demonstrations and activities) and presentations of their

findings.

Back to top

References:

(No author). (2010). The Beaufort Wind Scale. Retrieved from http://www.deltas.org/weer/beaufort.html.

Alameida, R. K. (1997, May). Nā makani o ka mokupuni. Honolulu, HI: Hawaiian Studies

Institute.

Beaufort scale. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaufort_scale.

Businger, S., da Silva, S., Ellinwood, I., and Chinn, P. (2012). Hadley cell and the trade winds of

Hawaiʻi: Nā makani mau [lesson plan]. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Retrieved from

http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/MET/Faculty/businger/kahua_ao/lessons/Lesson1.pdf.

Coriolis effect. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coriolis_effect.

Curriculum Research & Development Group (CRDG). (2011). Exploring our fluid Earth.

Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi College of Education.

Finney, B., and Low, S. (2006). Navigation. In K.R. Howe (Ed.), Vaka moana: Voyages of the

ancestors (154-197). Auckland, NZ: Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Fries, D. (1997). Start sailing right! (Rev. ed.). Portsmouth, RI: The United States Sailing

Association.

Heat transfer. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heat_transfer.

Irwin, G. (2006). Voyaging and settlement. In K.R. Howe (Ed.), Vaka moana: Voyages of the

ancestors (54-99). Auckland, NZ: Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Malo, D. (1951). Hawaiian antiquities (2nd ed.; N. B. Emerson, Trans.). Honolulu, HI: Bishop

Museum.

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

14

Pacific Resources for Education and Learning (PREL). (1996). Reading the wind: Navigation

and the environment in the Pacific [Teacher’s guide]. Honolulu, HI: Pacific Resources

for Education and Learning. Retrieved from

http://www.ethnomath.org/resources/prel1996.pdf.

Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS). (2012). Non-instrument weather forecasting. Retrieved

from http://pvs.kcc.hawaii.edu/ike/hookele/weather_forecasting.html.

Seidman, D. (1995). The complete sailor (2nd ed.). Camden, ME: International Marine.

Wind. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wind.

Back to top

These lessons have been developed in partnership with the University of Hawaiʻi College of Education and Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Funding has been provided by the Department of Education Native Hawaiian Education Program.

© Bishop Museum, 2014. All rights reserved.

15