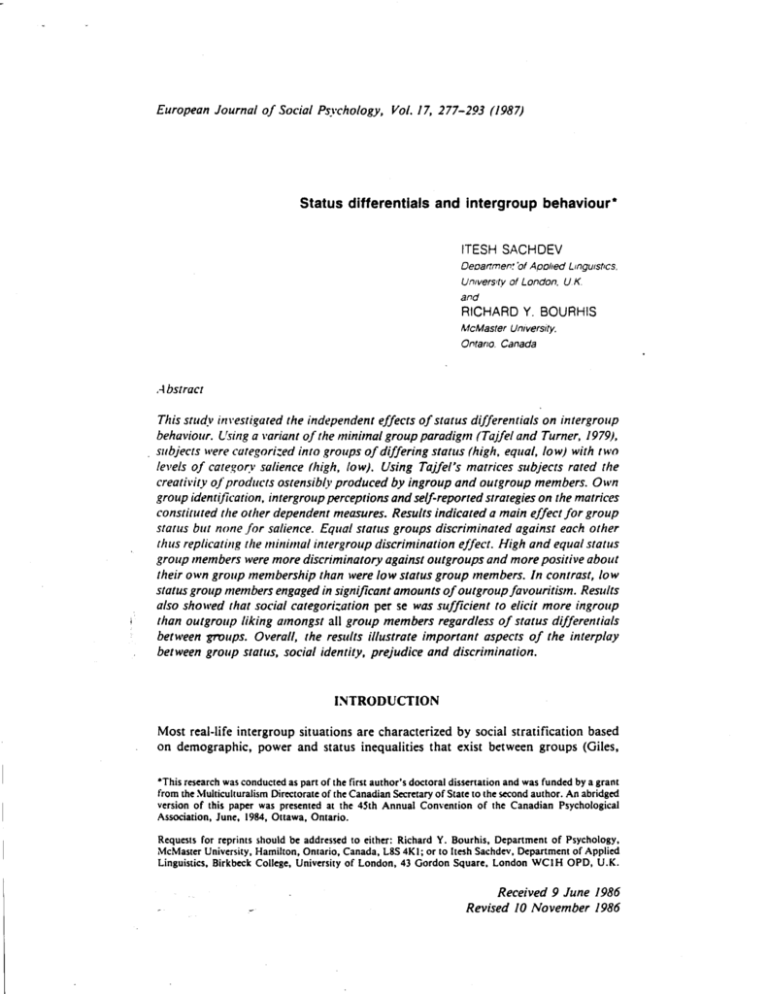

Status dilferentials and intergroup behaviour'

advertisement

European Journal

of

Social Psl,chology, Vol.17, 277-293 (1987)

Status dilferentials and intergroup behaviour'

ITESH SACHDEV

Deoartmen:'of Apolred Ltngusttcs,

UnMestv ol London, U K.

and

RICHARD Y. BOURHIS

McMaslq University,

Ontano. Canada

.lbstract

This study invesrigoted the independenr effects of sratus differentials on intergroup

behaviour. Lrsing a vdriant of the ntinimal group paradigm (Tajfel and Turner, /,979),

subjects were cutegorized into gtoups of differing status (high, equa!, Iow) with two

levels of catesory solience ftigh, low). Using Tajfel's matrices subjects rated the

creativity oJ'products ostensibly produced by ingroup and outgroup members. Own

group identification, intergroup perceptions and self-reported strategies on the matrices

constituted the other dependenr measures. Resa/rs indicated a main effect for group

status but none for salience. Equal status groups discriminated against each other

thus replicating the minimal intergroup discrimination e/fect. High and equalstatus

group members were more discriminatory against outgroups and more positive about

their own group mentbership than were low status group members. In contrast, Iow

status group members engaged in signiJicont amounts of outgroup favouritism. Results

also shorsed that social categorization per se was sufficient to elicit more ingroup

than outgroup liking amongst all group members regordless of status differentials

belween gvoups. Overall, the reshs illustrale important aspects of the interplay

between group status, sociol identily, prejudice and discrinination.

INTRODUCTION

Most real-life intergroup situations are characterized by social stratification based

on demographic, power and status inequalities that exist between groups (Giles,

'This research was conducted as part of thc first aurhor's doctoral dissenation and was funded by a grant

from the lvlulticukuralism Drectoratc of rhc Canadian Sccreury of State ro the sccond author. An abridged

version of this paper was presenred at rhe 45th Annual Convention of thc Canadian Psychological

Associarion, June, 1984, Ottawa, Ontario.

Requests for reprints should be addressed to either: Richard Y. Bourhis, Depailment of Psychology,

McMaster Univcrsity, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, LES 4Kl; or to ltesh Sachdev, Departmcnt of Applicd

Linguistics, Birkbeck College, Universiry of London, 43 Gordon Square, London WCtH OPD, U.K.

Received 9 June 1986

Revised I0 November 1986

278 I. Sachdev and R. Y. Bourhis

Bourhis and Taylor, 1977). However, experimenral social psychology has largely

ignored the systematic investigation of sociosrructural variables such as group

numbers, power and status differentials on intergroup relations. As one of a series

of studies investigating each of these sociostructural facrors (Sachdev and Bourhis,

1984, 1985), the present study was designed to assess the impact of srarus differentials

on intergroup behaviour. Our definition of group starus was the relarive position of

groups on valued dimensions of comparison such as educational achievement,

occupation, social standing, speech styles, etc.

Since the seminal results of Tajfel, Flament, Billig and Bundy (1971), a number

of 'minimal group' studies conducted with subjects of different'ages, nationalities,

and sexes using a variety of dependent measures have shown that the mere

categorization of people into two groups is suflicient to induce intergroup

discrimination (e.9. Billig and Tajfel, 1973; Brewer,1979; Tajfel, 1978, 1982a; Turner,

I980). In this research, discrimination refers to the action of favouring members of

the ingroup over members of the outgroup in the distribution of valued resources.

Tajfel and Turner (1979) propose that Social ldentity Theory (S.l.T.) provides the

most tenable explanation for minimal group discrimination. Social idcntity refers ro

'those aspects of an individual's self-image that derive from the social categories to

which he perceives himself as belongingl (Tajfel and Turner, 1979, p. .10). In its baresr

essentials, Social Identity Theory (S.I.T.) suggests that in many intergroup situations,

people seek positive distinctiveness for their own group to protect and enhance their

self-esteem (see also: Tajfel, 1982b; Turner and Ciles, l98l: Turner, Hogg, Oakes,

Reicher and Wetherell, in press). Thus, in the traditional minimal group experimenrs,

it was not minimal social categorization that caused discrimination but rather thar

motivations for positive self-evaluation could only be achieved by using the

experimentally imposed categorizations in a discriminarory fashion (see Turner, 1975).

In accordance with this notion, Oakes and Turner (1980) as well as Lemyre and Smith

(1985) obtained results which showed that increased self-esteem was positively related

to minimal group discrimination.

These classic minimal group studies employed groups that were implicitly of equal

status. Of course, real-life intergroup situations with groups of exactly equal status

are rare. Tajfel and Turner (1979) claim that group status has a porverful impact

on the social identities and intergroup. strategies of group membcrs. Through

unfavourable comparisons with outgroups, low status confers a negative social identity

and can constitute a threat to self-esteem. Horvever. to the degree that low status

group members acknowledge the superiority of high status group members on the

status-related dimension of comparison, S.I.T. predicts that low status group members

will show outgroup favouritism rather than ingroup favouritism (discrimination)

towards high status outgroups. Conversely, high status confiers a positive social idenriry

as it implies favourable comparisons vrs-ri-vrs low status outgroup members on relevant

dimensions of comparison. Thus, on the comparison dimensions that are consensually

perceived in favour of the high status group, S.I.T. predicts that high status group

members will discriminate against low status outgroups.

Laboratory studies investigating the link between group status, social identity and

intergroup discrimination have yielded contradicrory results. For instance, studies

conducted by Tajfel et al. (1971) and Commins and Lockwood (1979) employing

almost identical manipulations of high/low group status produced inconsistent results.

Whereas the former study found no differences in discrimination betrveen high and

Status dilferentials and intergroup

behaviour

279

low status groups, results from the latter study suggested that discrimination increased

rvith status. Commins and Lockwood's (1979) results were supported in a study by

Doise and Sinclair (1973) who found that high status group members discriminated

more than low status group members. In addition, low status group members in the

Doise and Sinclair (1973) study appeared to favour members of the outgroup rather

than members of their own group (i.e. displayed outgroup favouritism). In contrast,

Branthwaite, Doyle and Lightbown (1979) found that low status group members were

more discriminatory than high status group members. Results of a complex, though

statisticallv tenuous stud-v b_v Turner and Brown (1978) were also'at variance with

the other studies cited above. They suggested that high status groups did not

discriminate rvhen their superiority was perceived to be completely secure, However,

as in the Doise and Sinclair (1973) study, low status group members did display

outgroupfovouritisnt when allocating points to high status outgroups for status-related

performancc under legitimate and stable intergroup status conditions.

Further evidence suggesting that high status groups often benefit from favourable

outgroup responses.lvas recently obtairted in a complex study by Brown and Abrams

(1986). Amongst the results obtained in this study it was found that individuals

categorized as group members showed less evaluative bias against high status

outgroups thln against los' status outgroups. Finally, in a series of studies investigating

the personal and group social comparison strategies of high and lorv status groups,

Rijsman (1983) found that high status group members systematically outperformed

lorv status outgroup members as the former sought to establish that their personal

level of performance was commensurable with their high status group ascription (for

studies on personal versus group status reward allocations see Ng 1985, 1986).

Differences in subject samples, status operationalizations and dependent measures

may well account for some of the discrepancies noted in the above studies. ln addition,

although in previous studies both high status group membership and discriminatory

behaviour were supposed to provide group members with a positive social identity,

these laborarory studies did not direcrly assess the hypothesized links between status,

social identity and discrimination. Funhermorer status manipulation checks have either

not been successful (e.g. Branthwaite et al.,1979\ or have not been employed (e.g.

Commins and Lockwood, 1979). lndeed, neither Tajfel et al. (l91ll nor Commins

and Lockwood (1979) included reference to social 'prestige'or 'status' in their

instructional sets, or evaluated the importance that subjects attached to the status

dimensions used in the experiments. Finally, recent conceptual attempts to resolve

the above discrepancies have been mainly of a post Aoc nature (e.g. Van Knippenberg

and Wilke, 1979; van Knippenberg, 1984).

It was the equivocal nature of laboratory research on intergroup status differentials

that provided the impetus for the present study. The three major aims of the study

were: (a) replicarion of rhe traditional minimal group results; (b) investigation of the

effects of status differentials on intergroup behaviour; (c) examination of subjects'

perceptions of, and responses to, the experimentally imposed status categorizations.

Perceptions of relative status were established by dividing subjects into two groups

on the basis of false performance feedback on a creativity test. Subjects were

specifically informed that one's creativity was positively related to one's social status.

Subjects were then asked to rate products ostensibly created by other ingroup and

outgroup members using special matrices developcd by Tajfel and his colleagues (see

Turner, Brown and Tajfel, 1979).

280

I.

Sachdev ond

R. Y. Bourhis

Several methodological criteria were fulfilled to enable the assessment of the

independent effects of status differentials on intergroup behaviour and perceptions.

Subjects neither faced an intergroup conflict over scarce resources nor had the

opportunity to engage in direct self-interested actions. Croup memberships were kept

anonymous and Tajfel's matrices provided subjects with a variety of response

strategies including outgroup favouritism, parity, maximum joint profit, maximum

ingroup profit and maximum differentiation. Unlike mosr previous minimal group

studies the present research supplemented Tajfel's matrix allocations with subjects'

self-reported allocation strategies.

S.l.T. suggests that subjects in the traditional minimal groups'(implicitly of equal

status) fulfilled their motivations for a positive social identity by establishing

favourable intergroup comparisons (i.e. discriminated) on the only avarlable dimension

of comparison-Tajfel's matrices (see Turner, 1975). In the present srudy, the results

of a stable and legitimate creativity test (bogus) was used as the status dimension

to categorize subjects into equal or unequal status group members. On rhe basis of

this,' Hypot&esis /' was formulated thus: .subjectv'categorized, as members of equal

status groups would positively differentiate themselves from outgroups on available

dimensions of comparison through the use of discriminatory strat€gies on the Tajfel

matrices.

Our expectations concerning the effects of high and low status were derived from

S.I.T. and the discussion above. In the present study, both high and low status group

members were given an opportunity to rate the creativity of ingroup and outgroup

products using Tajfel's matrices. However, creativity was the very dimension that

a credible, prestigious and persuasive experimenter had used to establish the only

existing status difference between the two groups. Therefore, it was expected that

in order to assert their superiority on status-related dimensions, high status group

members would show greater discrimination (i.e. ingroup favsuritism) rhan low srarus

group members (hypothesis 2\.

Hypothesis J was formulated on the premise that low status group members did

accept the grounds for establishing the status differentials as being legitimate and

stable. To the degree that this was so, low status group members were expected to

show outgroup favouritism towards high status groups as an acknowledgement

of their 'inferiority' on the existing status-relared dimensions of comparison

(hypothesis 3).

Expectations about the intergroup strategies of equal status group members compared

to those of high and low status group members were more complex. The difficulty

in the case of equal and high status groups stems from trying to conceprually predict

the difference between discrimination to achieve and discrimination rc maintain a

positive social identity. Empirically, srudies comparing high and equal status groups

suggest that high status groups are more discriminarory than equal srarus groups (e.g.

Commins and Lockwood, 1979). It is arguably easier for high status group members ro

maintain andlor enchance superiorities on acknowledged dimensions of superiority than

for equal status group members to claim ascendancy on a dimension of comparison where

equality of status has been proclaimed. This is particularly the case when the srarus

equality is provided by a credible experimenter from an established scienrific discipline.

Comparisons of equal and low status group strategies were more straighrforward since

equal status groups were expectd to discriminate as in the usual minimal group studies

while low status groups were expected to show outgroup favouritism.

Status di/ferentials and intergroup

An attempt

behaviour

281

to assess the impact of salient and nonsalient status

categorizations on intergroup behaviour. Previous laboratory studies (e.g. Commins

and Locks'ood, 1979) have generally employed nonsalient manipulations of intergroup

status. Tajt'el (1978) and Brewer (1979) suggested that increasing the salience ofcategorization leads individuals to behave more in terms of their group memberships than in terms

of intra- or inter-individual factors. Previous minimal group studies (e,g. Billig and Tajfel,

1973; Turner, Sachdev and Hogg, 1983) suggested that explicit categorization operationalized by the mere mention of the label 'group' rvas sufficient in eliciting intergroup

discrimination. ln the present study both salient and nonsalient categorizations of the

groups were manipulated. The nonsalient categorization was achieved by only informing

subjects of the relative status of the two groups while the salient categorizadon was created

by explicitly labelling subjects as high, equal or low status groupmem&rs. Accordingly,

it was hypothesized that increasing the salience of status differentials should polarize

patterns of intergroup behaviour present in the nonsalient conditi ons (hypothesis 4).

The third aim of the study was to obtain subjects' perceptions of, and responses

to, the experimr'ntal situation. Civen that such perceptions have rarely been obtained

in previous rninimal group Iaboratory'studies, they were considered to be exploratory.

Of particular interest were measures designed to assess subjects' own group

identifications and intergroup preceptions. As in Sachdev and Bourhis (1985) who

rvas also made

also used estensive post session questionnaires, it was expected that group

categorizatior' per se would be sufficient to promote ingroup liking and outgroup

dislike (prejudice) regardless of the status manipulation.

METHOD

Subjects

Subjects were 120 Introductory Psychology students who volunteered as a partial

fulfillment of their course requirement. All subjects were English-speaking Canadians

between the ages of l8 and 2l who had lived in Southern Ontario for all of their lives.

Design

Subjects were run in group sessions (20 per session), with treatment condition

randomly determined for each session. There were six treatment conditions. Subjects

were categorized into different status groups ostensibly on the basis of their

performance on a creativity test. Half the subjects were exposed to a manipulation

aimed to make their group memberships more salient. The rest were in the nonsalient

conditions. Thesc manipulations yielded a3xZdesign matrix consisting of three levels

of status (high, equal, low) and two levels of salience (NS and S).

Procedure

A

male English-speaking Canadian experimenter introduced the study as an

investigation of aspects related to'creativity in academic settings'. Subjects were

instructed that they would be completing two creativity tests for this purpose. It was

impressed upon the subjects that creativity was an extremely imponant aspect of

intellectual functioning and that it correlated significantly and positively with social

282 I. Sachdev and R. Y. Bourhis

and occupational status both within and beyond the University setting, Subjects were

then asked to complete the first 'quick and often use, srandardized' creativity test

designed to provide an index of their creativiry. This test was adapred from Moscovici

and Paicheler (1978) and consisted of mocimizing rhe number of possible:rrangements

of horizontal bars whilc observing a specific set of rules. lt will suffice to say that

the scoring procedure of this test was made ambiguous enough to prevent subjects

from making realistic estimates of their own creativiry on rheir test. Previous piloting

of this test had shown that subjects found it neirher too difficult nor too easy.

While an assistant busily appeared to score subjects' responses on the first creativity

test, subjects were asked to complete a second creativity test. This consisted of crearing

a series of titles for an abstract print by an unknown artist. Upon completion, subjects

were instructed that the results from the first creativity rest were available. Feedback

(false) about individuals' creativity on the first test was provided by caregorizing

individuals (identified only by personal code-letters) into two groups (group X or

W) on the basis of their creativity performance. Specific instructions manipulating

the status variable \{ere theo given. In the high and lorv starus conditions, subjects

were told that their first creativity scores situated them in one of two groups: rhose

high in creativity and those low in creativity. In the equal status conditions, subjecrs

were told that their scores placed them in one of two equally creative groups that

only differed in the manner in which they completed the test.

For half the subjects, group status \ryas made satient by emphasizing the crearivilystatus link mentioned earlier and by labelling groups in the session explicitly as 'high,

equal or low status'. These subjects were then requesred to rvrite their group

identification labels in their response booklets. The nonsalient lnanipulation u'as

achieved by only informing subjecrs of the relative status of the two groups resulting

from the scores obtained in the first creativity test.

Following these manipulations the experimenter e.tplained that he was also inreresred

in investigating how subjects, themselves, evaluated the creativirl' of others. For this

purpose, subjects were asked to give their personal evaluarions o[ rhe creativity of

other individuals based on their performance on the second crearivity test (i.e. the

titles generated by others). The actual titles they rated were, in reality, consensually

prejudged by 200 other subjccts (from the same popularion) to be equivalent in

creativity. The titles were randomly presented as products of rwo orher subjects who

were identified only by their personal code lerters and rheir respective group

memberships. Subjects, in fact, always privately rated products ostensibly created

by a member of the ingroup (excluding themselves) and a member of rhe oulgroup.

The ratings were completed by using Tajfel's matrices to award points to sets of titles

ostensibly produced by ingroup and outgroup subjects present in the session. Following

the matrix distribution task, subjects compleled a postsession questionnaire. Finally,

subjects were carefully debriefed to mutual satisfaction.

Dependent measures

Matrix ratings

Our main dependent meaiiures were subjects' point-allocations to ingroup and

outgroup individuals using Tajfel's matrices. Four basic strategies can be assessed

using Tajfet's matrices (Turner et al., 1979). Parity (P) represents a choice which

Statrs differentials and intergroup

behoviour

283

arvards Equalnumber of points to a recipient from the ingroup and a recipient from

the outgroup. Absolute ingroup favouritism or profit (MIP) represents a choice which

awards the highest absolute number of points to the ingroup member regardless of

arvards made to the outgroup recipient. Relative ingroup favouritism or maximum

differentiation (NtD) represents a choice rvhich marimizes the dilference in points

awarded to trvo recipients, the difference being in favour of the ingroup member but

at the cost of sacrificing absolute ingroup profit. Maximum joint profit (MJP)

represents a choice rhat maximizes lhe rctal cotnbined number of points to both

ingroup and outgroup recipients. Though there has been some controversy about the

use and scoring o[ these matrices evidence from this study and previous research

indicates that the Tajfel matrices can monitor subjects' social orientations in a valid,

reliable and sensitive manner (see Turner, 1980, l983a,b Brown, Tajfel and Turner,

1980; Bornstein, Crum, Wittenbraker, Harring Insko and Thibaut, 1983a,).

Three matrix types (from Turner et a|.,1979), designed to measure the strengths or

'pulls' of the above strategies on subjects' choices, were used. The first matrix type

compared parit-v (equality, P) versus ingroup favouritism (FAV). Ingroup favouritism

(FAV) was made up of the strategy of ma.nimum ingroup profit (MIP) plus the strategy

of manimum differentiation (lvlD), (i.e. FAV = MIP + tvtD). The second matrix type

compared ingroup tar ouritism (FAV) versus ma,ximum joint profit (MJP). The third

marrlx type compared madmum differentiation (lvtD) versus combined absolute ingroup

profit and marimum joint profit (MIP+ MJP). From each matrix type, two pulls can

becalculated. Each pull has a theoretical range from - 12 to + 12. Negative strategy pulls

indicate pursuit of their psychological opposites, e.g. negative FAV indicates outgroup

favouritism, or the asarding ol more points to a member of the outgroup than to a

member of the ingroup. \,tatrices were randomly presented to each subject. Each matrlx

type was presented once in its original form and once in its reversed form in order

to obtain pull scores. This amounted to six matrix presentations in total. A manual

(Bourhis and Sachder, 1986) describing the Tajfel matrices and explaining the method

used to calculsre 'pull scores' is available from the authors upon request.

Postsession ques I io n naire

Several items on a postsession questionnaire assessed the following: (i) subjects' selfreportd matrix distribution strategies and their estimatc of strategies that other ingroup

and outgroup members employed; (ii) subjects' identification with ingroup, estimates

of other subjects' identification with ingroup and estimates of outgroup subjects'

identification rvith their groups; (iii) subjects' liking for other ingroup and outgroup

members and rheir estimates of other subjects' liking for them and ingroup and

outgroup ottfers; (iv) subjects' feelings about their own group membership including

estimated relative status and power of ingroup and outgroup; (v) subjects' responses

to the oeerimennl situation including the perceived legitimacy of the status differentials.

The above questionnaire items were all answered on seven-point rating scales. Copies

of the postsession questionnaire are available upon request from the authors.

RESULTS

This section is divided into two parts: analyses of subjects' matrix ratings, and their

responses on the postsession questionnaire items.

284 I. Sachdev and R. Y. Bourhis

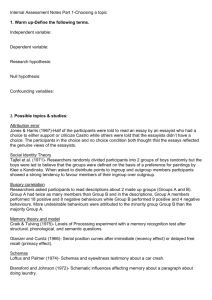

Analyses of subJects' matrix distribution strategies

Following Turner et al. (1919J and Brown er a/. (1980), 'pull' scores were calculated

for each strategy (see also Bourhis and Sachdev, 1986). Two sers of analyses were

conducted on these pull scores: (a) strategy analyses wirhin each treatment condition;

(b) strategy analyses between treatment conditions.

Strotegy analyses within each trestment condition

I presents the mean pull scores of each strategy for each cell in the design.

These were calculated and tested by performing Wilcoxon Matched Pairs tests on

the difference in scores between the ingroup/outgroup (l/O) an outgroup/ingroup

(O/l) versions of each matrix type. Overall, the strengths of each variable declined

Table

in magnitude in the order of: P on FAV, MD on MIP + MJP, FAV on P, FAV

on MJP, MIP + MJP on MD, and MJP on FAV. To test for anifactual dependence

between any two pulls calculated from the same matrix type, correlations were

calculated between the cell devia.tions of each pull and the absolute cell means of

the appropriate obverse pull (see Turner et al., 19791. No correlations were significant

suggesting that obverse pulls obtained from the same matri.r typc were not artifacrs

of compressed ranges.

Table I shows that the pull of parity (P on FAV) w:rs strong in all conditions. Despite

the strong pull of parity across all conditions, clear and systematic variations in the

use of other strategies emerged. As can be seen in Table l, results from equal status

groups supported hypothesis l. Equal status group members clearly discriminated

by employing significant levels of relative (MD on lvtlP + MJP) and absolute ingroup

favouritism (FAV on P and FAV on MJP).

Support for hypotheses 2 and 3 was also obtained. Whereas high status group

members discriminated a great deal, low status group members showed outgroup

favouritism. The pulls of relative ingroup favouritism (lr{D) and absolute ingroup

favouritism (FAV) were significantly positive in the high status conditions but negative

Table 3. Mean 'pulls' of subjects' matrix distribution srrategies

Low

Status

Matrix

slrategy

Nonsal.

(NS)

P

6.95.t

on FAV

MD

on lvllP + IvtJP

FAV

on P

FAV

on MJP

MIP+MJP

on MD

MJP

on FAV

'p<0.01.

tMean

. Equal

Salicnt Nonsal. Sailient

(s)

(NS)

(S)

-

1.85

-

1.25

-2.ffi'

1.85r

1.00.

E.65.

6.

10.

- I .70

7.0_(.

- 0.25 3.05.

Salient

(S)

X

1.70.

4.60.

6.29

3.6-s.

6.

_<'

5.70.

3. 1 7

3.80.

4.74.

4.7V

2.46

5.50.

4.20'

2.25

4.40.

4.25r

-

0.35

0.55

0.35 0,60

(NS)

6.75r

-2.25'

0.20

High

Nonsal.

0.05

1

t..r0r

0.10 - 0.50

L20

pull score for each matrix distribution stratcgics range from -12 to +12.

rp<0.05.

0.89

0.27

Status CiJferentiais and intergroup

behaviour

285

or not signiiicant in the iorv status conditions. Hon'ever results in Table I also suggest

:hat though \IJP (on F.\V) and \{lP + lIJP (on \1D) *,ere the leasr inilue'ntial

strategies in ihe stud-"-, thcse trvo strategies were adopted to a signiiicant degree by

ncnsaiient low status group members. Finallv, the 'rvirhin' conditions analyses

:ror i..ied lirric sr stemaric support lor hl pothesis -1.

,irrcie?_r' r,'r,,,,t1'se-r ile! v'een t red! nten

t

condit iorts

l,r Setie:-:t..j's n\potltr-'-ses l, -l .;nd J. a status (three levc'ls) b.y'categorl saiience

ii\\o ^e\eis) ;::itiir'.ariatc anair:is.ti rariance,r'as empioved *ith the six matrir puil

iitrr-cS JS i,..rerJenr,Tleasure:. The orerall \1ANOV.{ rercaied onlv a rnain eliect

ior :he staru5 . rnacie. fl i :. : i ) = l :l, p< 0.00l. Unirariare anair':es indrcarcd lhar

tne status nriin ciieci *as sipnliicant ior iour strategies; (i) F..\\ (on \1JP), F(:,

jlJ)=1.i.5J.:'(0.rIl:(iit\lD ron \flP - \lJP), F(], lll)=_11.1-(, p<C tr(')l:(iii)

F\\'16nPl,frl, ll-)=lS ii,r<Ct)01;rrr)P(onFA\'),F(:, t;-l)=-i.0;,p<0.01.

1

Subsequent ;Jmitansons (Duncan's

\lulripie

Range tesi

-

all conlDansons at p < 0.0-,.)

:r'.;i;err'd a ia:ge 11.:',:r-i':'ot -\unnor! ior hl,pothesis 3, supporr ior nvporhesis , bur

....:, i!l-nr.r,

":

F

!

..1. r..,,n,.,-,.J.1s .

-1

ln ac:orian;;' ',r 11x i1r'pctresr-s l. high t.t/= J.85) and equai (.11= l.-11) :itru-s 3raupS

nelnbers di-se:rminaiel .\,, 1i,'piaving higher FAV (on \lJP) rhan lo* i.',/= -:.i:)

:ialLls qroup rncnia.l's. in rddirrcn. htgh (.1/:5.93) and equal (,1/= J.1,5) srarus group

merrbers disc::rnrnale C bv sho* ing grearer ma.rimum diilere nriarion (!lD) rhan low

, 11- - i.-S).tuius group members. \\'hen FAV was pitred againsr P, hig (.11=-i.70)

rnd eouai t.l/ = .J3) status croups \r'er€ also mrrre discriminatory than lorv status

t.\/= -0.15)groups. Hor,,'ever,therewasnoindicationthathighstatusgrouprnembers

disc:iminateC nrore than equal sra(us group members. On all thL.se measures. the

negat!\e sccres oi lorv sratus groups clearly indicated outgroup t'avouritrsm, thus

..) rl.'or:rng 11r;rrtiicsrs i. Tirour:h lll

-zroups shorved large amounts r)l pant\'(P on

F.\\'), lorv struus group members (.1/=7.80) dispiayed more pariry,than high status

group membcrs (.t/= .1.6-5).

Finallv, resulls ol lhe o\erail 3 x 2 \tANOVA provided no support lor hy'pothesis

J. The manipulations aimed to make eategories more saiient did not seem to affect

lnlergroup behaviour ln this exDeriment.

-1

.{nalyses

of

postsesslon questionnaire

Due to the large number of questionnaire items, an overall status by salience

\IANO\'.{ uas conducted on all dependerrt measures. A significant main eflect rvas

obtarned only' ior th€ status variable, F(78, 152) = 5.99, p<0.001. Univariate anai-vses

indicated that thrs main eflect rvas highly significant for itens listed in Tablc 2. As

our salience manipulation did not seem to aflect subjecrs'responses, the results are

presented collapsed across salience of condition. The MANOVA main effect was also

signiiicant for other dependent variables which were more appropriately analysed

by 'repeateC measures' analyses that are reported later.

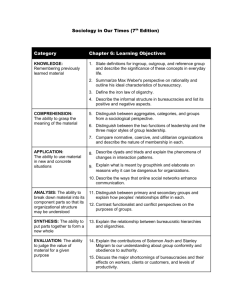

Results in Table 2 show that high and equal status group members had more positive

feelings associated with their group membership and the status differential than low

status group members. Duncan's l\{ultiple Comparison tests indicated that high and

equal status group members felt more comfortable, satisfied and happy than low status

286 I.

Sachdev and

R. Y. Bourhis

Table 2. Perceptions of group membership and sratus differential (collapsed across salience)

Status

Low

Equal

Variable

Comfortable with group

Hieh

F(status)

43.96, p<0.001

(2, r r4)

2.63b..

4.93..b

5.70

2.20b

2.23b

4.25".b

5.88"

4.29.'b

5.98r

66.62, pco.00t

73.46, p<O.001

creativir!'test

3.0Eb

4.39"

4.23'

Fairness of

categorization

8.69, p<0.001

2.70b

3

.83"

3.93u

9.54, p<0.001

status differential

Personal value of

2.23b

3.85.

3.63a

18.87, p< 0.001

creativity

5. t5d

5.8S

5.78.

3.22, p<0.05

Satisfied with group

Happy with group

Fairness

of

Legitimacy of

fromb at p<0.0t.:'differs from at p<0.05.

highcr the mcan ratingon the 7-point scale, the higher rhe score on rhc item.

d

'differs

'The

group members. Indeed, high status group mem ers were also more positive about

their group membership than equal status group members.on rhese measures. In

addition, high and equal status group members lound the experinrental procedures

for measuring creativity and categorizing subjects to be more agrceable rhan did low

status group members. Table 2 also shows that high and equal starus group members

perceivd the status differential to be more legitimate than lorv srarus group members.

Interestingly, though all subjects valued creativirt, hiehly (all group means over 5 on

a 7-point scale), low status group members seem to undervalue creativity relative to

the other groups (Table 2).

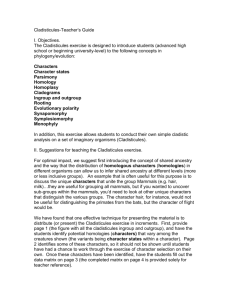

Importantly for S.I.T., a number of items asking subjecrs lo esdmare ingroup

identification (of members of both groups) and 'liking' for members of both groups

were analysed by repeated measures ANOVAS with an o priori significance crirerion

on p<0.001 for each lest. One significant interaction el't'cct rvas

obtained:

status x group identificatior, F(4, 228) =24.80,p < 0.001. Table 3 shows thar the high

and equal status group members showed higher levels of owngroup identification

than low status group membcrs. In addition, low and high srarus members seemed

to have similar expectations about the degree of group identificarion reporred by orher

low and high status group members. Both groups felt that high starus group members

would identify more than low status group members rvith their respective ingroups.

The analyses also revealed repeated measures main effects for the following

imponant intergroup perception measures: (a) subjects' estimated liking for orhers,

Table 3. Subjects' estimates

(collapscd across salience)

Identification by:

Self

Other ingroup

Other outgroup

of ingroup idenrificarion

b;- selt and others

Low

Status

Equal

Hish

3.3ob.c..

3. ggd.b

4.99r

3.4Eb

4.13.r

5.3r

4.65.

{.ld

3.5 5b

'differs from ar p<0.01.;'differs from c at p<0.05.

Thc highcr the mean rating on the 7-poinr scale, thc higher the scorc on rhe item.

b

'

Sratns differentials and intergroup

behaviour

287

f'( I , I l4) = 12.28, p < 0.001; (b) subjects' estirnates of other ingroup members' liking

lor others, F(2,2281=40.29, p<0.001; (c) subjects' estimates of outgroup members'

liking for others, F(2, 228)=25.28, p<0.001. Duncan's pairwise comparisons

indicated that (p <0.01 for all comparisons): (a) subjects would like ingroup members

1,\{ = 4.731more than outgroup members (M = 4.27). (b) subjects also felt that other

ingroup members would like them (M4.88) and other ingroup members (M=4.80)

more than outgroup members (r|fa.03); (c) subjects estimated that outgroup members

n ould like other outgroup members (M = 1.92'l more than themselves (.1/ = 4.27) and

orlrer members of the ingroup (.1/=.1.12). Thus social categorization per se was

sufficient in eliciting more ingroup than outgroup liking amongst all group members

regardless of status diflerentials between groups.

Results of manipulation checks revealed that all subjects agreed that highly ceative

people had higher status (M=5.55) than rhose low in creativity (i,/=3.33), F(1,

I l.r) = 196.6l, p< 0.001. These perceptions did not seem to be differentially affected

b:- the status or salience manipulations. A repeated measures ANOVA (status x

saliencexingroup/outgroup) on subjects' reported perceptions of ingroup and

oulgroup status revealed a significant status by repeated'measures interaction (F(2,

I lJ) = 19t4.63. p<0.001). Duncan's lVtulriple Comparison tests showed that all groups

accurately perceived the status differentials imposed in the experiment. Indeed, while

lon'status group members perceived they had less status (M=2.401than the high

sratus group (M= 5.08), high status group members rated they had more status

(.1/ = 5.25) than the low status group \M = 2.65\, Equal stalus group members rated

they had as much status (M=3.65) as outgroup members (M=3.451.

Did subjects accurately report the use of their actual strategies on the matrices?

In general, analyses indicated no differences between conditions on the self-reported

strategies of parity, ingroup favourirism and maximum joint profit. There appeared

to be a general tendency for mid-scale responses on most of these measures, regardless

ol subjects' actual use of these straregies on the matrices. The one exception to the

above results were responses on self-reported outgroup favouritism. Low status group

members seemed to accurately report their actual use of outgroup favourirism, while

high and equal status group members accurately reportd their non-use of tils strategy.

In addition, self-reported outgroup favouritism was significantly and negatively

correlated with matrix measures of ingroup favouritism (e.g. self-rcported outgroup

favouritism with FAV on MJP, r= -0.43, lI8 df, p<0.001).

What were subjects' estimates of rhe strategies that other ingroup and outgroup

members employed relative to rhem? Since these could not be asscsscd direaly from the

IIIANOVA analyses, univariate repeated measures ANOVAS were conducted on

subjects' estimates of strategies employed by themselves, other ingroup and outgroup

members. Using an a priori significance criterion of p<0.001 for each test, the analyses

revealed two significant effects: (a) a main effect for estimates of ingroup favouritism,

F\2,228) = 17.65, p < 0.001; and (b) an interaction effect for group status x estimat€s

of outgroup favouritism, fl4,2281=25.82, p <0.001. Painrisc comparisons indicated:

(a) subjects felt that they (M= 3.3E) showed less ingroup favouritism (p < 0.01) than

other ingroup (M=4.08) and outgroup members (M=4.15); (b) low status group

members reported showing more outgroup favouritism than all other groups. However,

low and equal status members did not expect othcr subjects (ingroup or outgroup) to show

outgroup favouritism. ln contrast, high status group members expected low status

group members to favour high status group membcrs in their ratings of group products.

288

I.

Sachdev and

R.

Y. Bourhis

Finally, were subjects aware of the purposes of the experiment? Whereas responses

from the majority of subjects (102) suggested that subjecrs were not at all aware of

the experimenter's hypotheses, a small minoriry of subjects (14) felt that the experiment

was concerned with ingroup favouritism. Analyses indicared that this minority was

not distributed across the design in any systematic manner. Furthermore, these

subjects' responses were not predictive of their actual choices on the matrices. Only

four subjects indicated awareness of experimental hypotheses. However, their

responses did not seem to be predictive of their behaviour on the matrix choices.

DlscusstoN

The overall results from the matrix ratings provided support for hypotheses l, 2 and

3. As expected on the basis of our first hypothesis, the traditional minimal intergroup

discrimination effect was obtained in the equal status categorization conditions (Tajfel

and Turner, 1979). Equal status perJe does not provide a positive social identity as

it does not imply a favourable comparison with the outgroup. Therefore equal status

group members discriminate on available dimensions of comparison (i.e. the matrix

ratings) in order to achieve a positive social identit-v. The slrong inlluence of relative

(MD) and absolute ingroup favouritism (FAV) on equal status group members' matrix

choices provides direct evidence for this notion.

Our second hypothesis also received strong support from matrix choice results.

In particular, high status group memhrs were more discriminatory than low status

group members on matrices assessing both relative and absolute ingroup favouritism

(MD, FAV). Thus, high status group members did assert their superiority on the status

dimension by discriminating against low status group members even though the

ingroup/outgroup titles they were rating had been prejudged to be equally creative.

As expected on the basis of hypothesis 3, lorv status group members lavoured

members of the outgroup on the status-related dimension of creativity via the matrix

ratings. However, low status group members' levels of outgroup favouritism were

not high relative to their levels of parity. This suggests that though low status group

members acknowledged their inferiority through outgroup favouritism responses

(negative FAV), they may also have attdmpted to minimize the magnitude of the

unfavourable social comparison through parity responses which were much stronger

than those of high status group members. Perhaps the significant levels of MJP and

MIP + MJP responses shown by nonsalient low status group members also reflected

an attempt by this group to minimize the negative impact of their unfavourable

comparisons with the high status outgroup.

It is difficult to draw specific conclusions regarding hypothesis -l l'rom the present

study. lncreasing the salience of categorizations did not seem to polarize intergroup

behaviour. However, there was little indication that our labelling operationalizations

of salience were successful in actually varying the salience of the intergroup situation.

Future research employing stronger manipulations of calegory salience may prove

more informative.

S.I.T. interprets intergroup discrimination as a means of differentiating the ingroup

from the outgroup in a positively valued direction. Therefore, discrimination should

lead to a positive social identiy (c/. Lemyre and Smith, 1985). Results from the present

study were generally consistent with this interpretation. For example, high and equal

Starrs differentials and intergroup

behaviour

289

status group members reported that they fett more comfortable, satisfied and happy

about their respecrive group memberships than low status group members. However,

status position per se, regardless of actual discrimination, also conributes ro group

members' social identities (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Relative to low and equal status,

high status provides a favourable differentiation before subjects are given the

opportunitl' to discriminate. Accordingly, results from the present study suggest that

high status group members felt more positive about their group membership and

showed higher levels of group identification than both equal and lorv status group

members. Further supporr lor this analysis rvas provided by partialling out the effects

oI matrix discrimination from correlations of group status with reported feelings

rorvards thc. ingroup. As Table .l shorvs, the partial correlations between reported

status and leelings associated with group membership after partialling out matrix

discrimination (MD, FAV), were all significantly positive. Thus, the present results

are consistent rvith the notion that status per se can contribute to group members'

social identiries over and above the contribution made by discrimination.

Table.l. Panial correla(ions berrvcn group status and feelings associated with group membership

alier partialling out matrix ingroup favouritism (lvlD, FAV)

Variable

partialled our

\lD on NllP + i\lJP

F.\V on IIJP

FAV on P

Feelings associated rvith group membership

Satisfaction

0.61'

0.63f

0.61.

Comfort

0.59r

0.57.

0.55*

Happy

0.68'

0.67.

0.66.

'=p<0.001. tlf =119.

The above analysis may also help account for the fact that contrar)'to expectation

high status grcrup members \\'€re not more discriminatory than equal status group

members. With high statuspersecontributing to positive social identity. discrimination

rvas not so necessary as a means for these group members to positively differentiate

from the lorv s(atus outgroups. However it remains that the influence of relative and

absolute ingroup favouritism (iVtD, FAV) rvas qirite strong for both high azd equal

status groups. Thus, these results suggest that the maintenance of favourable status

differences for high status group members was as important as lhe achievement of

positive differentials was for equal status group members.

Results of the present study indicated+hat low status confeyred a somewhat negative

social identity on subjects. Consistent with our expectations, individuals categorized

as lorv status group members reported the lorvest levels of group identification in

the design. Indeed, subjects trom high and low status groups expected low status

to produce lorver degrees of social identification than high status. In addition, high

status group members also expected low status group members to accept their

'inferiority' and show outgroup favouritism on status-related dimensions, which is

indeed what lorv status group members did in rheir matrix responses. Low status group

membership does not contribute favourably to positive social identity. Thus, low status

group mernbers in our study had difficulty identifying strongly with their group

membership though they could not completely deny their ascription to the low status

category as it was based on a 'standardized and reliable' creativity test. However, as

290 I. Sachdev and R. Y. Bourhis

in field studies where the possibility of passing to the high starus group is improbable

(Bourhis and Hill, 1982), low status group members in our study perceived the

intergroup situation to be less legitimare than did high status group members. In

addition, though all subjects reponed that creativit)' was extremely important to them

personally, low status group members undervalued crearivity relarive to high and equal

status group members. Furthermore, as noted earlier, it does appear that despite their

outgroup favouritism responses on the FAV and MD strategies, low status group

members did seem to use the parity and MJP strategies as owngroup serving responses

to improve their position vr's-d-r'rs high status outgrorrp member. Taken toge(her,

the matrix responses along with patterns of identification and intergroup perceptions

probably helped low status group members reduce threats to rheir social identity

implied by the unfavourable experimentally imposed social starus caregorization. These

results lend support to Tajfel's (1978) contention that individuals prefer to belong

to groups that provide them with a positive social identity.

It should be noted that the pres€nt study creatcd a staric and ahistorical

intergroup situation that did not allow low status group members to redefine or

create alternative dimensions of comparisons as in studies s'ith real-life groups

(e.g. Bourhis and Hill, 1982; Brown, 1978; van Knippenberg, 198-l). Field studies

can incorporate the historical dimension rvhich dcmonstrabll" aftccts the strategies

high and low status group members develop to enhance their social idcntities.

Future studies with real-life groups will help assess how and rvhen group members

come to employ different strategies of redefinition to serve thcir social identit.v

needs.

Finally, Tajfel's (1978, l982a,b) important categorization effect rvas obtained on

inlergroup perception measures across a// conditions in this e.rperiment. In generai,

all subjects, regardless of group status, felt that rhey and other members of both

groups would like thier respective ingroup members more than ourgroup members.

Thus. categorization per se was sufficient to trigger prejudicialarrirudes amongst all

group members regardless of status differentials bels'ecn groups (sec also Brerver and

Kramer, 1985).

In conclusion, we have perhaps identified quite lundamental effects of status

on intergroup behaviour. A number of predictions derived from Social ldentity

Theory (Tajfel and Turner, l9?9) were supported in this stud;". \lethodologically,

the use of an extensive postsession questionnaire provided valuable insights into

relations between different status groups. ln particular, we sere able to assess

rhc-interplay between group status, social identit_v, prejudice and discrimination.

In laboratory, Zrs in everyday life, the structural constraints implied by group

status differentials seem to have imponant psychological implications for the conduct

of intergroup relations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Peter Forsyth, Clorianna Tucker,

and John Blythe for their help in the data collection phase of this research. We

also wish to thank Michael Hogg, Rochelle Cole, Silk Hung Ng, John Rijsman

and two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on earlier versions of

this paper.

Status differentials and intergroup behaviour

29r

REFERENCES

Billig, M. and Tajfel, H. (1973). 'Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour',

European Journol of Social Psychology, 3: 21-52.

Bornstein, C., Crum, L., Wittenbraker, J., Harring, K., Insko, C. A. and Thibaut, J. (l9E3a).

'On the measurement of social orientations in the minimal group paradigm', European

Journal of Social Ps-vchology, 13: 321-350.

Bornstein, C.. Crum, L., \\'ittcnbraker, J., Harring, K., Insko, C. A. and Thibaut, J. (1983b).

'Reply to Turner's commcnts', European Journal of Social Pslchology, 13: 369-381.

Bourhis, R. Y. and Hill. P. (1982).'lntergroupperceptionsin Bririshhighereducation: A field

study'. In: Tajfel, H. (Ed.) Socail ldentity and Intergroup Relations, Cambridge University

Press and Edition de la lr'taison des Sciences de l'Homme, Cambridge and Paris, pp.423-468.

Bourhis, R. Y. and Sachdev. l. (1986). The Tajfel Motrices as an lnstrument lor Conducting

Intergroup Reseorch, lllci\laster University Mimeograph, Hamilton, Ontario.

Branthwaite, A., Doyle, S. and Lightbown. (1979). 'The balance between fairness and

,discrimination', European Journal of Social Fsycholog;*. 9: l{9-163.

Brelver, lvt. B. (1979). 'lngroup bias in the minimal group situation: A cognitive-motivational

analysis', Psychologicol Bulletin, t6: 307-124.

Brewer, M. B. and Kramer, R. ilt. (1985). 'The psychology of intergroup attitudes and bchavior',

.4nnual i?evierv of Psl,chology, 36: 219-243.

Brorvn, R. J. (1978). 'Divided we fall: an analysis of relations betrveen sections of a factory

rvork-force'. In: Tajt'el, H. (Ed.) DilJerentiation Between Social Groups, Academic Press,

London and Nerv York, pp. 395429.

Brorvn, R. and Abrams, D. { 1986}. 'The effects of intergroup similarit}'and goal interdcpendence

on intergroup attitudes and task performance', Journal of Experimental Socisl Psychology,

22:7E-92.

Brown, R. J., Tajfel. H. and Turner, J. C, (1980). 'Minimal group situations and intergroup

discrimination: Commen(s on the paper by Aschenbrenner and Schaefer', European Journal

of Sociol Psychologlt, l0: 399-.114.

Commins, B. and Lockwbod, J. { 1979). 'The effccts of status differences, favoured treatment

and equity on intergroup comparisons' , European Journal of Sociat Psychologt, 9: 2E I -289.

Doise, W. and Sinclair, A. (1973). 'The categorization proccss in intergroup relations', Europeon

Journql oJ' Sociol PsS'chologl',3: 145-157.

Ciies, H., Bourhis, R. Y. and Ta.vlor, D. (1977). 'Towards a rheory of language in ethnic group

relations'. ln: Giles, H. (Ed.) Longuoge, Ethnicity and Intergroup Relotions, Academic Press,

London.

Lemyre, L. and Smith, P. lvl. (1985). 'lntergroupdiscrimination and self-esteem in thc minimal

group paradigm', Journal of Personality and Social P$'chology,49: 660-670.

lrloscovici, S. and Paicheler, G. (197E). 'Social comparison and social recognition: Two

complementary process€s of identification'. ln: Tajfel, H. (Ed.) Differentiation Between

Social Groups, Academic Press, London, pp. 251-266.

Ng, S. H. (1985). 'Biases in reward allocation resulting from personal status, group status,

and allocarion procedure', Austaliqn Journal of Psychologlt, 37: 297 -307.

Ng, S. H. (1986). 'Equity, inrergroup bias and interpersonal bias in reward allocation', European

Journql of Social Psychologl, 16: 239-255.

Oakes, P. J. and Turner, J. C. (1980). 'social categorization and intergroup behaviour: Does

minimal inrergroup discrimination make social idcntity more positive2' Europeon Journal

of Social Psychologlt, l0: 295-301.

Rijsman, J. (19E3). 'Thc dynamics of social comparison in pcrsonal and categorical comparisonsituations'. ln: Doise, W. and Moscovici, S. (Eds) Cunent /snres rn Europeon Social

Psychologt, Vol. l, Cambridge University Press and Edition de la Maison des Sciences de

I'Hommc, Cambridgc and Paris.

Sachdev, I. and Bourhis, R. Y. ( l9E4). 'Minimal majorities and minorities', Europan tournal

of Social Psychology, 14: 35-52.

Sachdev, L and Bourhis, R. Y. (t9ES). 'sosial categorization and power differentials in group

relations', European Journal of Social Psycholog!, t5: 415-434.

Tajfel, H. (Ed.) (lyt8). Diflerenriotion Betwen Sxial Grcup,l+qdemic Press, London, pp. l-98.

292 I.

Sachdev and

R.

Y. Bourhis

Tajfel, H. (1982a). 'Social psychology of intergroup relations', Annual Review ol Psychology,

33: l-30.

Tajfel, H. (Ed.) (l9E2b). Social ldentity and Intergraup Relations, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Tajfel, H., Flament, C., Billig, M. and Bundy, R. (t971). 'social categorizarion and intergroup

behaviour', Europeon Journsl of Sociol PsychologSt, l: 49-l?5.

Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. C. (1979). 'An integrative theory olintergroup conflict'. ln: Austin,

W. G. and Worchel, S. (Eds) The Sociol psychology ol Intergroup Relations, Brooks/Cole,

Monterey, CA., pp. 33-47.

Turner, J. C. (1975). 'Social comparison and social idenrirl': Some prospects for intergroup

behaviour', European Journal of Social Psychology,5: 5-34.

Turner, J. C. (1980),'Fairness of discrimination in intergroup behaviour? A reply

to Branthwaite, Doyle and Lightbown', European Journal of Sociol Psychology, l0:.

l3t-t47.

Turner, J. C. (1983a). 'Some comments

in the minimal group paradigm"',

35 l

on.

"the measurement of social orientations

of Social Psl,chology, 13:

Europeon Jownal

-367.

Turner, J. C. (1983b). 'A second reply to Bornstein, Crum, Wirtenbraker, Harring, lnsko

'and Thibaut on thc tncasurement of social orientations', EuroBean Journot of Social

Psychology, 13: 383-387.

Turner, J. C. and Broum, R. J, (1918). 'Social satus, cognitive alternaives and intergroup relations'.

In: Tajfel, H. (Ed.) Diflereniaian Betv'een Sociol Groups. Academic Press. London, pp. l0l-Ia.

Turner, J. C., Brown, R. J. and Tajfel, H. (1979). 'Social comparison and group inreresr in

ingroup favouritism', European Journql of Social Psychologl',9: IE7-204.

Turner, J. C., and Giles, H. (Eds) (1981). Intergroup Behoviour, Blackrvell, Oxford.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D. and \\'etherell, \1. (Eds) (ln press).

Rediscovering the Social Group: A Se$-Cotegorization Theor.t', Blacknell, Oxford.

Turner, J. C., Sachdev, I. and Hogg, M. A. (1983). 'Social categorizarion, interpersonal

attraction and group formation', British Journal of Social Psl'cholog.r'.22.221-239.

Van Knippenberg, A, and Wilke, M. (1979). 'Perceptions of collegiens and apprentis reanalysed', Europeon Journol of Social Psychology,9: il7-.134.

Van Knippenberg, A. (1984). 'lntergroup differences in group perceprions'. ln: Tajfel, H. (Ed.)

The Social Dimension, Vol. t and 2, Cambridge Universitl Press and Edirion de la llaison

des Sciences de I'Homme, Cambridge and Paris, pp. 560-S78.

RESUME

Cette recherche 6tudie les effets ind6pendants des diff€rences de sratuts sur le comportemenr

intragroupe. En utilisant unc variante du paradigme du groupe minimal {Tajfel et Turner,

1979), on a cat6goris€ les sujets dans des groupcs i diffirents statuts (iler€, €gal, bas) avec

dcux degris de saillance catdgorielle (haut et bas). En utilisant les matrices de Tajfel. les sujers

ivaluent la cr6ativite de produits ostensiblement fabriques par des membres de 'l'in.groupe'

et de'l'hors-groupe'. L'identification de son propre groupe. les perceptions intergroupes er

les strat€gies repon6es par les sujets dans les matrices, constituent les autres mcsures dipendanres.

Les resultats indiquent un effet principal pour le statur du groupe mais pas pour la saillance.

Les groupes i statuts 6gaux font des discriminations entre eux, repliquant ainsi I'effer de

discrimination intergroupe minimal. Les membres des groupes I statut 6levi et 6gal font plus

de discriminations i l'€gard de 'l'hors-groupc' et se montrent plus positifs envers l'appartenance

i leur propre groupe que les membres des groupes i bas statut. En revanche, les membres

des groupes A bas statut font preuve d'un favoritisme significativement important pour 'l'horsgroupe'. Les risultats montrent aussi que, pour toal les mcmbres des groupes ind6pcndamment

du statut propre i chaque groupc, la catdgorisation sociale per Je n'est pas suffisante pour

provoqucr plus de prdf€rencc pour son propre gxoup€ que pour I'autre groupe. Dans I'ensemble,

les resultats illustrent d'importants aspects de I'intcraction flttre le statut des groupes, l'identite

sociale, les prejug6s et la discrimination.

Status differentials and intergroup behaviour

293

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

In der vorliegenden Arbeit wurden unabhiingige Effekte von Status-unterschieden im Intergruppenverhalten untersucht. Unter Nurzung des Paradigmas der minimalen Cruppenbedingungen

surden Vpn in Gruppen unterschiedlichen Status (hoch. gleich, niedrig) mit zwei Stufen der

Deutlichkeit der Kategorisierung (hoch. niedrig) eingeteilt. Tajlel's Matrizen wurden

ange*endcr, um die Kreativitit ron Ergebnissen zu beurteilen, dievorgeblich von ingroupund

outgroup-irlitgliedern erzeugt sorden sind. Die ldentifizierung mit der eigenen Gruppe,

Intergruppen-Wahrnehmung und Aussagen iiber die bei den Beuneilungen angewandte Strategie

saren rveitere abhiingige Variable.

Die Ergebnisse zeigten einen Haupteffekt des Gruppenstatus, aber keinen der deutlichkeit

der Karegorisierung. Cruppen von gleichem Status diskriminierten einander. Damit wurde der

Diskriminicrungseffekt fiir Cruppen unter Minimal-bedingungen repliziert. Mitglieder von

Cruppen mit hohem und mit gleichem Status beurteilten outgroup-Mitglieder in stiirkerem MalJe

diskriminierend und die ingroup-llirglieder positiver als dies bei Mitgliedern von Gruppen mit

niedrigem status der fall war. lm Gegenreil, Mirglieder von Cruppen mit niedrigem Status zeigten

einen signilikanten Betrag an outgroup-Bevorzugung. Die Ergebnisse zeigten auch, dafJ

Kategorisierungen an und frir sich ausreichen, um eine Bevorzugung der ingroup gegeniiber der

ourgroup zu erzeugcn, dics gilr l'ur alle Cruppenmitglieder unabhdngig von Statusunterschieden

zrvischen den Gruppen. lnsgesamr verdeutlichen dic Ergebnisse den wichtigen Aspekt der

\\'echselwirkung zrvischenGrupp€nstalus, sozialcr ldentitiit, Vorurteil und Diskriminierung.