VOL. 3, NUM. 1

WINTER/INVIERNO 2006

“Beethoven” and “Sigue Beethoven”:

The Sonata-Form Structure of Galdós’s La desheredada

Vernon A. Chamberlin

It has been demonstrated that while creating the novel Tristana, as well as the first volume

of Fortunata y Jacinta, Galdós did clearly follow the musical pattern known as sonata form.1

This musical design is most frequently used as the basic structure for the first or last

movement of a sonata (and sometimes also for the first movement of a symphony, as in

the case of Beethoven’s Third [Eroica] Symphony). In creative fiction it has served as a

model for such well-known authors as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, E. M. Forster,

Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, and Anthony Burgess.2 Because Galdós suggests in two

consecutive chapters, “Beethoven” and “Sigue Beethoven,” that La desheredada might be

read as if it were a sonata, the purpose of the present study is to explore the structure of

the novel as sonata form, as has been done with Tristana. Further, we shall suggest why

Galdós chose La desheredada to be the first of his sonata-form novels.

Musicologist Leonard Ratner has pointed out that one of the most distinguishing features

of the sonata form is its similarity to a formal argument or debate, with the main parts

being the exposition, development, recapitulation, and coda:

The first premise is the home key, represented by thematic material which

we shall call A.

The second premise is the contrasting key, represented by thematic material which we shall call B.

The home key makes its point with A; the point is refuted by the contrasting key with B. This refutation takes longer to accomplish than

the initial argument; it also makes its final point with great emphasis. (We are now at the end of the exposition.)

The premise of contrasting-key material is undermined by the digressions

and explorations of the development.

Home-key A material returns (recapitulation) to reestablish the first premise, but in order to settle the argument and reconcile the two contrasting premises, the home key later incorporates the B material,

showing that there can be unity, after all, between A and B. To

Decimonónica 3.1 (2006): 11-27. Copyright 2006 Decimonónica and Vernon A. Chamberlin. All rights

reserved. This work may be used with this footer included for noncommercial purposes only. No copies of

this work may be distributed electronically in whole or in part without express written permission from

Decimonónica. This electronic publishing model depends on mutual trust between user and publisher.

Chamberlin 12

make its point more powerfully, the home key asserts itself with

great emphasis (coda). (240)

Galdós’s novel La desheredada follows a similar structural plan, and the main

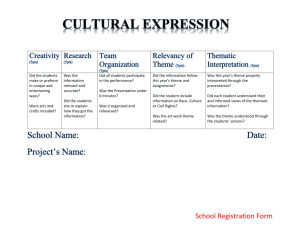

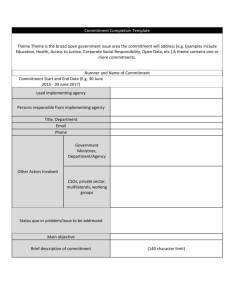

correspondences between this novel and a typical sonata form can be outlined as follows:

Musical equivalent

Exposition

Initial A theme

Initial B theme

A theme restated

B theme restated

Transition to development

Development

Recapitulation

Coda

Galdós’s chapters

Volume I, Chapters 1-3

Volume I, Chapter 1

Volume I, Chapter 2 and Chapter 3,

paragraphs 1-383

Volume I, Chapter 3, paragraphs 39-70

Remainder of Volume I, Chapter 3

Volume I, Chapter 4

Volume I, Chapters 5-18

Volume II, Chapters 1-9

Volume II, Chapters 10-17

Volume II, Chapter 18

Let us now examine the details of Galdós’s working out of this pattern. We shall do so in

chronological order, beginning with the exposition.

Exposition

In this opening portion Galdós, like a musical composer, presents (in the customary

symmetrical pattern) the main themes he will be working with throughout the rest of the

novel. He commences by presenting his A theme—illusion and irrationality4—as the

novel opens with a focus upon the extravagant and bizarre behavior of mental patients in

the Leganés asylum. The most notable inmate, and incarnation of the A theme, is Tomás

Rufete, the father of Isidora, the protagonist. However, before the end of the first chapter,

one sees that Isidora, who has come to visit her father on the day he happens to be dying,

does not herself live in a world of complete reality. She affirms that Tomás Rufete is not

her biological father, and the assistant to the asylum’s director, who at this juncture seems

grounded in reality and very wise, plays into Isidora’s illusion: “[Sí], entiendo, entiendo.

Usted, por su nacimiento, pertenece a otra clase más elevada, sólo que circunstancias

[. . .] le hicieron descender [. . .]” (I, i, 1: 27).5 However, this assistant, Canseca, soon

becomes unhinged himself; we learn that he has also been a patient here for thirty-two

years, and thus may be considered yet another personification of the A theme. After the

asylum’s director has to tell Isidora that her father has died, Augusto Miquis, a young

medical student who happens to be a childhood acquaintance from Isidora’s home town,

consoles her and offers to accompany her back to Madrid. Together, they leave the

asylum, “la morada de la sinrazón” (I, i, 4: 35), as Galdós concludes the initial

presentation of his A theme.

After the presentation of the opening A theme, Beethoven characteristically created a

“connecting episode.” Galdós follows suit with a focus upon Isidora’s existing thoughts

Chamberlin 13

and feelings. This focus continues until her visit the next day to her aunt, Encarnación

Guillén, popularly known as La Sanguijuelera.

Now clearly following the sonata-form pattern, Galdós’s B theme (his answering contrast

to the A theme) predominates in chapters 2 and 3. This new theme—reality—is made

manifest by means of the chapter-title protagonists, La Sanguijuelera and Mariano. The

former, Isidora’s sixty-eight year old aunt, is quite grounded in reality, which is a

prerequisite for surviving as an independent shopkeeper in a lower-class Madrid

neighborhood. After some getting-reacquainted visiting, the colorful Sanguijuelera takes

Isidora to visit her thirteen-year-old brother, Mariano, who is working in a rope factory

under the most horrible conditions. Here we certainly see the harsh reality of life as it is,

vivified by the all-too-common nineteenth-century exploitation of child labor.6 Clearly

the two eponymous chapter protagonists, individually and in tandem, offer a strong

contrast to those who had earlier personified the A theme, as Galdós now completes his

initial answering and contrasting B theme.

As in the music of a sonata form, Galdós’s A theme now comes back to emphasize its

previous premise. The author does this (II, iii) as Isidora elaborates on her earlier

statement to Canseca in the Leganés asylum: Tomás Rufete is not her father. Moreover,

she affirms that she and her brother are children of a marquesa, and she has legal

documents to prove her claim. Thus, as is customary in the sonata-form pattern, Galdós’s

A theme now has returned with greater intensity, while at the same time it presents a

number of sub-themes that open possibilities for further development.

At this juncture, as in a musical composition, the B theme is given a final chance for

rebuttal. La Sanguijuelera, who has a “gran sentido para apreciar la realidad de las cosas”

(I, iii: 55), begins mocking Isidora’s aristocratic pretensions with deflating sarcasm.

Finally, she grabs a stick and beats Isidora on the head. When the stick breaks, she

combines the two parts and is able to strike still harder, even after Isidora falls to the floor.

Although Isidora would like to resist, “devolviendo cólera por cólera, hubo de rendirse al

fin [. . .]. En sus veinte años, Isidora tenía menos fuerza que la sexagenaria Encarnación”

(I, iii: 56). Clearly the B theme is much the stronger here, and it has triumphed in its

contention with the A theme.

Thus we have arrived at the end of Galdós’s exposition. The two themes—illusion and

irrationality versus reality—have been presented, rebutted, re-presented, and once again

rebutted. Both themes are now ready for further development and interplay throughout

the rest of the novel, significantly with the B theme having had the last word in the formal

or debate sense and showing so much more strength than the A theme as to make its final

triumph at the end of the novel seem likely.

Transition to the development section

In music—and certainly in Beethoven’s sonatas—there is nearly always a transitional

passage (using the A theme) that leads to the development section. In Galdós’s novel, a

similar transitional passage occurs in chapter 4. Having recovered from the beating by

her aunt, Isidora now reveals her thoughts and feelings as she interacts extensively with

Chamberlin 14

Miquis during his guided tour of well-known sites in Madrid: El Retiro, El Prado, and La

Castellana. Very importantly, Isidora considers herself too highborn and sophisticated for

any romantic involvement with the reality-grounded medical student. Then at the climax

of the chapter (with transcendent authorial foreshadowing of the novel’s ending) Isidora

enthusiastically identifies with the “[mujeres de] las mantillas blancas” (I, iv, 4: 81-82)—

prostitutes hired to protest the reign of Amadeo I—whom she mistakenly believes are

aristocratic ladies, worthy of emulation. Thus we see the A-versus-B counterpoint of

reality/pragmatism and illusion/fantasy, set forth in yet another variation.

Development section

Before entering into a discussion of the long development section, let us pause to consider

the main features of this part of the sonata form. The purpose of this section, as its name

suggests, is to develop the themes set forth in the exposition. The composer is at liberty to

unfold and explore the manifold possibilities in each theme, modifying, fragmenting,

complicating, and embellishing as much as his talent will permit. This is one of the more

challenging segments of a sonata-form structure and a place where the composer may

demonstrate his resourcefulness and imagination. However, there is one thing a composer

must do: he is obliged to undermine gradually the key of the B theme (which had

appeared the stronger, more triumphant at the end of the exposition) so that its ultimate

surrender and subsequent fading away, near the end of the entire sonata-form section,

will seem logical and readily acceptable to the listener. Ratner states that “as a rule, the

section called the development goes far afield harmonically, creating a great deal of instability; toward the end the harmony settles so that a cadence to the home key of the A

theme is first promised, then accomplished at the recapitulation [the section following the

development and preceding the coda]” (238).

Let us now see how Galdós creates his own novelistic parallel to a musical development

section (I, v-II, ix). Basically he is unfolding and exploring various possibilities of his

contending illusion and reality themes, illustrated through a beautiful young provincial

woman who disdains working for a living and attempts to reside in the Spanish capital

and pursue an irrational lawsuit. The latter is part of a completely unrealistic quest to

become acknowledged as a biological member of an old aristocratic family. As the

contending themes continue to interact, a number of sub-themes (initiated already in the

exposition) are also given attention. These include Isidora’s haughtiness, her love of

luxury, her belief that her brother can be educated, and her financial irresponsibility.

With chapter 5 opening the development section, the A theme predominates as Isidora

reacts to the fact that a handsome aristocrat, the Marqués viudo de Saldeoro, has left his

calling card. This causes her to feel so superior to Miquis that she breaks off an

engagement to attend the theater with him. Thus she can devote the entire evening to her

fantasies, even imagining in great detail how each of the next four days and evenings will

transpire.

Not included in her fantasies are the everyday events of her brother and his associates.

Thus the B theme can and does predominate as chapter 6 realistically features boys at

Chamberlin 15

play. Climactically the realistic elements turn violent with Mariano killing another boy

and being arrested (I, vi, 3: 111-19).

Meanwhile the A theme is continuing (chapter 7) as Isidora goes shopping in Madrid.

First she stops for Mass, but the service for her is only a backdrop for reverie. Now it is

revealed that her notion about being the as-yet-unrecognized daughter of a marquesa

comes from novels she has read: “Yo he leído mi propia historia tantas veces” (I, vii: 123).

Her weakness for luxury and superfluous items, as well as her inability to be practical with

her money, are repeatedly demonstrated in this chapter, entitled “Tomando posesión de

Madrid.” Thus, when she arrives home,“cargada de compras” (I, vii: 127), and learns of

her brother’s arrest, she has difficulty even scraping together enough money for cab fare

to visit him in jail.

In chapter 8 Galdós introduces three new voices of his A theme. The first is José

Relimpio, a blood relative of Tomás, Isidora, and Mariano Rufete. As such, this “hombre

que no servía para nada” (I, viii, 1: 130) carries the same hereditary traits that predispose

the family towards irrational thought and behavior. So also does his son Melchor, whose

manifestation of the family weakness is seen in repeated, completely unrealistic get-richquick schemes. Of a different sort is Melchor’s mother, Doña Laura. Although a

representative of reason vis-à-vis her delusionary boarder Isidora (I, viii, 2: 141), Laura

reveals herself to be out of touch with reality concerning all aspects of the life of her

unemployed son, Melchor.

An important innovation of an entirely different kind occurs in chapters 9 and 10 as

Galdós gives a purposeful authorial clue to the sonata-form structure as pattern for the

entire novel.7 In chapter 9 (“Beethoven”) he presents the grandson of the Marquesa de

Aransis actually playing a piano sonata, while simultaneously Galdós grants a look at the

Aransis family history. Galdós’s descriptions of the intricacies of Beethoven’s artistry (I, ix,

1: 158-59) display the author’s ability to pattern a work of his own using musical

techniques and analogies. The narrator says (in part):

Una idea sola, tan sencilla como desgarradora, aparecía entre el vértigo de

mil ideas secundarias y se perdía luego en la más caprichosa variedad de

diseños que puede concebir la fantasía, para aparecer al instante

transformada. [. . .] De modulación en modulación, la idea única se iba

desfigurando sin dejar de ser la misma, semejanza de un historión que

cambia de vestido. Su cuerpo subsistía, su aspecto variaba. (I, ix, 1: 158)

External evidence also indicates that Galdós’s knowledge of Beethoven’s sonatas was

sufficient to enable him to follow the latter’s structural designs. Rafael Moragas indicates

that Galdós’s mastery of Beethoven’s music was achieved by strenuous application:

“[D]on Benito descifraba trabajosamente las sonatas de Beethoven en un armonium que

tenía cuando vivía [. . .] en Madrid” (qtd. in Verdaguer 176). A letter from Manrique de

Lara confirms Moraga’s suggestion that Galdós worked hard at analyzing Beethoven’s

compositions. Apologizing to Galdós for having to miss an appointment, Lara remarks,

“Confío en que mañana podré hacerlo y no sólo podremos concertar el andante de

Beethoven, sino hacer un primeroso y detenidísimo estudio de la harmonia” (qtd. in

Chamberlin 16

Sopena Ibáñez 26). The letter also suggests that Lara was serving as a consultant to

Galdós, for he notes, “Tenga la seguridad de que para mí es una honra muy grande y un

verdadero placer el ser de alguna utilidad para Vd.” (qtd. in Sopena Ibáñez 26). Yet

another friend who knew that Galdós was interested in the analysis of Beethoven’s works

was the pianist and composer Joaquín Malats, who wrote to Galdós: “Ahora estoy

estudiando la sonata op. 111 de Beethoven [. . .] ya verá Vd. Es sencillamente

monumental” (qtd. in Sopena Ibáñez 136). And Galdós himself said in 1902 in the prólogo

to Alma y vida:

Tracé y construí la ideal arquitectura de Alma y vida, siguiendo por

espiritual atracción, el plan y módulo de la composión beethoviana, y no

se tome esto a desvarío, que el más grande de los músicos es quien mejor

nos revela la esencia y aun el desarrollo del sentimiento dramático. (900)

However, in chapter 10 of La desheredada (“Sigue Beethoven”) Galdós, who was both a

consummate pianist and organist, acknowledges how challenging a Beethoven sonata can

be. Even as Isidora is visiting the Aransis mansion and fantasizing about possessing its

luxuries, the narrator’s friend, Dr. Miquis, attempts to play one of the sonatas in the book

left on the piano. Before long he has to acknowledge his insufficient talent: “—¡Pobre

Beethoven mío!—exclamó el estudiante, dejando de tocar y haciendo un gesto de

desesperación—. ¡Qué lejos estabas de caer entre mis dedos!” (I, x: 171).

In chapters 9 and 10 Galdós also continues with his customary A-theme/B-theme

contention. Isidora voices the A theme as she identifies with the luxuries of the Aransis

mansion and persists in the illusion that they will soon be hers. Juan Bou, the realitybased proletarian from the other extreme of Spain’s social structure, is the contrasting Btheme representative.

Additionally, one might even postulate an A-theme/B-theme interplay concerning the

Beethoven sonata itself. The narrator talks about the difficulties of playing Beethoven

(theme B); Miquis tries to play it and fails (theme A, optimism and illusion, overcome by

theme B, his inability to play it well). The latter also contrasts with the inherent beauty of

Beethoven’s music when played well (theme A).

In contrast to the second sonata player, Galdós himself shows no evidence of any

difficulties in following his own structural plan, for in chapter 11 (“Insomnio número

cincuenta y tantos”) he again presents his A theme, now with unrelenting vigor. Isidora’s

fantasies are now so intense that each night they keep her awake hour after hour. Not

only does she believe that she will be rich, but also that the Marqués will marry her. Her

one realistic insight into her personal circumstances occurs near the end of the chapter

and concerns her health: “En mi cabeza hay algo que no marcha bien. Esto es una

enfermedad” (I, xi: 176).

A respite from such intensity, and a complete change of pace, occurs in chapter 12 (“Los

Peces [Sermón]”) as Galdós leisurely introduces the Pez family. Only at the climax of the

chapter does it become clear how much this political family incarnates the B theme, since

they are interested in helping Isidora only because her uncle (el canónigo) in La Mancha is

Chamberlin 17

their local representative. Certainly they do not see any validity in Isidora’s aspirations:

“Esto es novela. [. . .] Admitámoslo en las novelas ¡pero en la realidad . . . !” (I, xii, 3:

190). Even more suggestive, Isidora’s beloved marqués (Joaquín Pez) is only interested in

seduction.

Thus it is understandable that the A and B themes collide head-on in chapter 13

(“Cursilona”) as Joaquín Pez attempts to obtain sexual favors. In exchange for financial

support, he offers to install Isidora in a house of her own. Although greatly tempted,

Isidora resists and Pez loses his composure, labeling her cursilona (I, xiii: 197).

After Pez and Isidora reconcile, Galdós intensifies his narrative—appropriate at this

juncture for a novel whose first volume will be published separately—by bestowing upon

his B theme the vigor of a musical cadential drive. That is, he has harsh reality

predominate through four chapters (I, xiv-xvii), which include all but the final chapter of

volume I. Thus in chapter 13 (“Navidad”) the misery of Isidora’s situation is emphasized

through juxtaposition with the Relimpio family’s Christmas Eve merrymaking. Isidora

and her brother, Mariano, are forced to eat alone in her room. With good humor, Miquis

(always a representative of the B theme) pops in to deprecate her fantasies. She, however,

is in no mood to enjoy this, as she is able to offer only very meager food to her brother,

and the latter is unappreciative and highly insulting. Then (in “Mario promete” [I, xv])

the brother subsequently drops out of school and “descendió [. . .] hasta el nivel más bajo,

concluyendo por incorporarse a las turbas más compatibles con su fiereza y condición

picaresca. Granujas de la peor estofa [. . .] formaban su pandilla” (I, xv: 221).

Subsequently, the climax of volume I occurs as the Marquesa de Aransis (in “Anagnórisis”

[I, xvi]) tells Isidora personally and emphatically that her pretensions are without merit

and that Isidora certainly is not her granddaughter. As a consequence, the denouement of

volume I becomes Isidora’s reaction to this reality, including her sexual surrender to

Joaquín Pez (I, xvii), who had earlier offered to establish her as his mistress in a house of

her own.

Notwithstanding the strong cadential drive just described—which really closes the story

line of volume I—Galdós brings back the A theme in a coda-like chapter for

enhancement (paralleling the customary musical coda at the conclusion of an entire

sonata-form structure). This is accomplished as the final chapter (I, xviii) explains clearly

why the A theme has been so strong and so persistent throughout the volume, and why

accordingly it thus merits the final (debate-like) statement.

Entitled “Últimos consejos de mi tío el canónigo,” this chapter illustrates in great detail

how, since very early childhood, Isidora has been indoctrinated by her mentally ill uncle

with the multiple errors and fantasies which she has revealed throughout volume I.

Moreover, the illusion theme is delightfully corroborated here by the fact that the uncle

lives in La Mancha and is surnamed Quijano-Quijada; his letter of consejos to Isidora is

clearly a parody of Don Quijote’s advice to Sancho prior to the latter’s becoming the

governor of an island.

It is significant to note that in the chapter just described, Galdós has departed from the

usual sonata-form pattern. Ordinarily, one would not expect to see such a coda-like

Chamberlin 18

chapter at the midpoint of a sonata-form novel. However, since La desheredada was

published in two volumes, it needed a good, strong, reader-satisfying chapter to close

volume I. This was done by capping the B-theme cadential drive of chapters 14 through

17 with an A-theme coda in order to have the volume be a self-contained, aesthetically

pleasing work of art in its own right (and marketable to the public). Thus Galdós’s

departure from the musical pattern was dictated by the demands of the publishing format

and does not constitute a flaw in the novel’s sonata-form structure.

Volume II

Galdós’s initial chapter of volume II picks up the story line thirty-four months after the

close of volume I. Dr. Miquis has told the narrator what has happened to Isidora since

the reader last saw her. Isidora has now been set up as a kept woman by the Marqués

Saldeoro in a house of her own. Although the Marqués (Joaquín Pez) has not married her,

she has given birth to a macrocephalic child. Certainly the latter is a reflection of one of

the aspects of the A theme, for Dr. Miquis warns Isidora that her “deliriante ambición y

vicio mental le darán una descendencia de cabezudos raquíticos” (II, i: 256).

Appropriately this chapter is entitled “Efemérides” (diary or journal), for each paragraph

in the second half of the chapter begins with a date (for example, “1873. 1o de marzo”)

and tells what is happening in Isidora’s life (the A theme), juxtaposed against a

background of concurrent national events (political turmoil and civil war), which show

that the B or reality theme is also still continuing in this second volume. By the time the

monarchy has been restored (early 1875), Isidora has activated her lawsuit and still has

her love of luxuries, but a new reality of discord with Pez (about money and other

women) as well as new problems with her brother now plague her.

Chapter 2 (“Liquidación”) is tripartite. The first section is devoted exclusively to the A

theme as the narrator addresses Isidora directly and admonishes her for living a “vida

ilusoria y fantástica” (II, ii, 1: 267). He finds particularly detrimental her love of luxuries,

her lawsuit, her illusion that her brother can be educated, and, especially, her waste of

time and money on Pez. The second section of the chapter illustrates the seriousness of

the latter problem. Isidora has received a letter from Pez, who once again needs money,

so she implores her aunt, La Sanguijuelera, to loan her 2000 reales. Clearly functioning again

as an incarnation of the B theme, La Sanguijuelera once more has an opportunity to point

out Isidora’s weaknesses before she agrees to the loan. Even such a loan is not sufficient,

and Isidora has to supplement by sending José Relimpio out to pawn personal items. The

third and final section of the chapter presents Isidora as still moneyless and having now

pawned nearly all her furniture (except her bed).8 Consequently, she decides that she will

have to earn a living. Having read about other young women who were forced to work in

order to pass from “la humildad de la buhardilla al esplendor de un palacio,” she exults:

¡La honrada pobreza y la lucha con la adversidad cuán bellas son! Pensó,

pues, que la costura, la fabricación de flores o encajes le cuadraban bien, y

no pensó en otras industrias, pues no se acordaba de haber leído que

ninguna de la heroínas se ocupara de menesteres bajos, de cosas

malolientes o poco finos. (II, ii, 3: 281)

Chamberlin 19

Emphasis on the A theme continues in the next chapter (II, iii), entitled “Entreacto en la

iglesia.” A month after we last saw her, Isidora still has had no time to select an

occupation: “Entre bañarse, peinarse, vestir y arreglar a ‘Riquín’ [su hijo], se le iba la

mañana” (II, iii: 285). In the afternoons she likes to go to church, not only for the

superficial aspects and pomp of the services, but more insistently to see and envy the

important and aristocratic people present. She fantasizes that winning her lawsuit will

soon allow her to take her proper place among them. However, José Relimpio (who has

been Isidora’s A-theme companion in the most recent chapters while he enthusiastically

keeps their financial records) now tells her that she is not only broke, but deeply in debt.

Consequently, Isidora has no recourse but to accept as a lover/protector the very

opposite of her heart’s desire: Sánchez Botín, a non-elegant, older, non-aristocratic,

repugnant man whose attention she repeatedly attracted at church. Although Galdós

does not repeat the presentation in volume I of characters playing a Beethoven sonata,

the title of the fourth chapter of volume II, “A o B . . . , Palante,” might lead the reader

into thinking of two contending (musical) themes as he or she approaches the chapter.

Might Galdós be inviting the reader to speculate which theme will be featured in this new

chapter? In any case, in the opening paragraph the narrator reiterates the clear-cut

distinction between Isidora (always an incarnation of the A theme) and her brother,

Mariano (B theme).9 Then Galdós decides to proceed with the B theme, subsequently

bifurcating it as he moves from a focus on Mariano to the introduction of a new

personification of the reality theme, the lithographer Juan Bou. The latter is the

proletarian entrepreneur to whom Mariano becomes apprenticed. The rest of the chapter

focuses on Bou, his business, his apprentices, and his relationship with Mariano. Only at

the end of the chapter does the narrator reveal that Juan Bou likes (as does Galdós) to

think in binary terms, and to move them forward, as we see that both “A o B” as well as

“palante” are speech and thought characterizations specific to Bou (II, iv, 2: 301-04)—

and that they are probably the source of the chapter’s title. Nevertheless, by leaving the

title unexplained, Galdós has made connections again with the musical substructure.

Chapter 5 (“Entreacto en el café”) serves as a transition from B back to A. Mariano, now

seldom working and addicted to gambling and womanizing, spends a great deal of time in

a café. José Relimpio, continuing to represent the A theme, comes to the café seeking

solace from Mariano. He feels this need because Isidora’s new protector, Sánchez Botín,

refuses him admission into the house where the latter has installed Isidora as his mistress.

Relimpio subsequently serves as a conduit to an end-of-chapter focus on Isidora. The

latter is as beautiful and well-dressed as ever, but her reputation has disintegrated. As she

is about to go forth on a mysterious errand, the narrator reveals, “[C]uantos la

encontraban sabían que [ya] no era un lady” (II, v: 311).

Notwithstanding Isidora’s new status as Sánchez Botín’s mistress, she has a secret

assignation with Pez (“Escena vigésima quinta” [II, vi]), where she enthusiastically gives

full rein to her A-theme tendencies. Pez, now for the first time, functions also as primarily

an A-theme representative, especially as he excuses his past failures and misconduct: “Yo

vivo en lo ideal, yo sueño, yo deliro y acato la belleza pura, yo tengo arrobos platónicos”

(II, vi: 322). However, Pez has enough grip on reality to accept the money (which Isidora

has raised with great difficulty) and to refuse to recognize their child legally.

Chamberlin 20

The A theme with a focus on Isidora continues in chapter 7. She is in fact the title

protagonist, its “Flamenca Cytherea” (or Venus flamenca). Rebelling against Sánchez Botín

and his domination, Isidora defies his prohibition to participate in Madrid’s annual

Romería de San Isidro:

El vestirse de pueblo, lejos de ofender el orgullo de Isidora, encajaba bien

dentro de él, porque era en verdad cosa bonita y graciosa que una gran

dama tuviera el antojo de disfrazarse para presenciar más a su gusto las

fiestas y divertimientos del pueblo. En varias novelas de malos y buenos

autores había visto Isidora caprichos semejantes, y también en una célebre

zarzuela y en una ópera. (II, vii: 326)

When Isidora returns from the romería, she finds Sánchez Botín furious also because he

has learned that she had pawned (in order to help Pez) some of the jewelry that he had

given her and replaced it with fakes. Much harsher reality than she had expected now

assaults Isidora, as Sánchez Botín terminates their relationship, and she leaves his house

that very night. The B theme continues to predominate now as her former protector tells

the departing Isidora, “Isidora [. . .] oye la voz de un amigo. Vuelve en ti, reflexiona,

acuérdate de lo que muchas veces te he dicho. ¿Por qué no has de entrar en una vida

ordenada? Yo estoy dispuesto a auxiliarte, proporcionándote un estanco. [. . .] Puedes

contar con el estanco” (II, vii: 333-34).

Reality continues to triumph over Isidora in chapter 8 (“Entreacto en la calle de los

abades”). Forced to take refuge in José Relimpio’s house, now commandeered by his son

Melchor, Isidora’s impracticality and love of luxuries soon has her so compromised

financially that she is forced to surrender sexually to Melchor. This unhappy situation is

resolved only when Melchor is forced to flee the city, just one step ahead of the police. As

occurred at the end of the previous chapter, Isidora is once again without a protector,

and, most importantly, now without funds for everyday necessities.

A third, more sincere protector offers himself to Isidora in the following (ninth) chapter

(“La caricia del oso”). Here the A and B themes clash intensely as Mariano’s employer,

Juan Bou, and Isidora tour the Aransis mansion. While Isidora silently takes great

pleasure in examining all the mansion’s treasures (which she thinks her lawsuit will soon

obtain for her), Bou vociferously denigrates them all. For Isidora, this is “la profanación

más odiosa. Era como el hereje que pisotea la hostia” (II, ix: 356). Bou also offends her

sensibilities when he abominates the aristocracy and wishes for its destruction. Only when

he discovers Isidora weeping in a bedroom where she has found refuge does Bou

remember Isidora’s lawsuit and that this mansion is the very one to which she aspires. His

subsequent, sincere proposal of marriage is rejected as Isidora experiences “horror y asco.

Toda la nobleza de su ser se sublevó alborotada, llena de soberbia; [. . .] ella era noble”

(II, ix: 358-59). Thus one sees clearly that at this point in the novel there is no possibility

of a reconciliation of the contending A and B themes. Both themes are still in strong

opposition, and their contention must continue.

We are, however, now at the end of the development section. The author has certainly

explored the possibilities of what can happen to a beautiful, young provincial who

Chamberlin 21

disdains working for a living as she attempts to live in the capital and pursue an irrational

lawsuit. Even the harshest kind of reality, as was prefigured at the end of the exposition

section when La Sanguijuelera savagely dominated Isidora, seems now to be no match for

the A theme’s protagonist. Thus we see that, analogous to the dynamics of a sonata-form

structure, the strength of Galdós’s B theme has been weakened, as it has interplayed with

the A theme throughout the development section. As evidence of this we note, for

example, that La Sanguijuelera herself is now reconciled to Isidora and even facilitates her

irrational behavior by loaning her money. Moreover, Juan Bou, the incarnation of the B

theme here at the end of the development section, is easier for Isidora to deal with than

was La Sanguiuelera at the end of the exposition.

Recapitulation

The recapitulation section in a typical sonata form brings about a final settlement of the

A-theme/B-theme contention or argument which has been the structural framework of

the entire movement to this point. As the word “recapitulation” suggests, the material is

also a restatement and review of the most important ideas and elements that have gone

before—specifically, the basic conflicts are once again expressed. In addition, the

composer must demonstrate that, in spite of the A-theme/B-theme contention, these two

main themes can indeed coexist and have in fact some capacity for a certain amount of

harmony and compatibility. Although this may have been shown from time to time

earlier, it must now be demonstrated explicitly in order to prepare the listener to accept

the yielding of the B theme at the end of the recapitulation section (rather than to expect

the complete annihilation of one or both themes).

A musical composer can, in his or her recapitulation section, restate literally note for note

the earlier material in precise chronological order. A novelist, of course, cannot, since he

or she must constantly be introducing new material to hold the reader’s interest and to

move the story forward.10 This is Galdós’s technique as he reviews (recapitulates) for the

reader the fundamental conflict between illusion and reality—originally presented in the

exposition—as Isidora continues to experience life in Madrid.

Let us see how Galdós accomplishes this recapturing of themes. Remembering, of course,

his original sequence and symmetry, our author begins the recapitulation with emphasis

upon the A theme. Just as a musical composer may present the listener with the repetition

of a theme in a different key, so Galdós, early on in his recapitulation, shows his

consummate skill as a novelist by the interesting variations on his original themes. Thus

we find (II, x) that although Isidora still believes in her nobleza and suffers from “el loco

amor al lujo y las comodidades,” she, her son, and her godfather actually have nothing to

eat (II, x, 1: 362). For help she turns to Miquis, who recalls (recapitulates) their long-ago

Sunday-afternoon outing: El Retiro, El Prado, a shared orange, and his flirting with her

(II, x, 1: 367). Once again Isidora is soon living in a private home, and again it is with the

Relimpios. Now, however, with Doña Laura deceased, Isidora and her godfather live

with the latter’s married daughter (II, x, 2: 371-83). As in the exposition, Isidora cannot

bring herself to do any work. Soon she again desires fine clothing, for now the modista who

made her dresses when she was the mistress of rich men, lives upstairs. Miquis catches her

there, but she again rejects his admonishments. Joaquín Pez again has a profound effect

Chamberlin 22

on Isidora. Now he does not leave a fancy calling card; rather, he is poverty-stricken.

After again being a disappointment to her host family, Isidora leaves them to become

once more a kept woman, this time by Bou. Nevertheless, she is soon seeing Pez again;

now instead of his bringing her money to survive, it is the other way around. Once again

Isidora and Pez give full rein to their fantasies (II, xii, recalling II, vi). He tells her she will

win her lawsuit, he will marry her, and they will travel the world together. She, however,

now prefers to remain single and fantasizes about the luxuries she will soon have. Harsh

reality soon follows these A-theme illusions when Isidora is arrested for falsification of

documents (II, xii: 407-08).

Chapter 13 of volume II (“En el Modelo”) illustrates well our earlier assertion that a

novelist (unlike a musical composer) cannot recapitulate material from the exposition

section literally, nor in exact chronological order. Were this the case, Galdós would have

begun his recapitulation section with Tomás Rufete in the Leganés asylum. However, he

chooses to recapitulate this setting later in the volume when he places Isidora herself in a

situation analogous to that experienced by her father. Imprisoned on the charges of

document falsification, Isidora is incarcerated in Madrid’s newly constructed women’s

prison.11 Miquis is again present, and the sights and sounds of the institution are evocative

of those presented in the novel’s opening chapter at the Leganés asylum. Once again the

A theme shows great strength, as Isidora adapts to prison life by imagining that she is

Marie Antoinette, a classic symbol of delusion (II, xiii: 411).

But paralleling Galdós’s technique at this stage of his exposition, the B theme becomes

dominant when Mariano’s behavior again deteriorates. For some time now he has not

only been associating with the lowest dregs of society, but has even been planting terrorist

bombs (II, xiv, 1: 429-30). Finally, in a recapitulative echo of his earlier killing of a boy,

he buys a pistol and attempts to kill the king (II, xvi: 456).

The title of the last chapter in Galdós’s recapitulation section (“Disolución” [II, xvii]) is

quite appropriate, as now nearly all of Isidora’s illusions dissolve. Reality at last triumphs

over irrationality and illusion. After Mariano’s attempted regicide, Isidora realizes that

there is no hope of educating and reforming him. Additionally, now tired of imagining

herself in the role of Marie Antoinette (II, xvii, 1: 459), Isidora signs documents

relinquishing aspirations to the Aransis aristocracy in order to terminate her

imprisionment.12 She must also give up her illusion of a life with Joaquín Pez, el Marqués

Saldeoro, for he has returned from Cuba a married man. Even her recently formulated

contingency plan to marry Juan Bou has to be abandoned, for he has also married. Thus

it is appropriate for Galdós to conclude his recapitulation section by recalling Isidora’s

kept-woman status, since she now has to accept a new lover/protector.13 The latter is

Gaitica, a gambler from the lowest dregs of society, who entices Isidora into his casapalacio, saying:

Una persona que sale de la cárcel no puede hallarse en disposición de

atenderse a las primeras necesidades. Así, cuando usted entre por puerta,

hallará una modista y un chico de la tienda de sombreros que irá con

muestras. [. . . Además] allí tengo un cuarto de baño. (II, xvii, 2: 466)14

Chamberlin 23

For a time Isidora again seems to flourish and is repeatedly seen elegantly dressed. Before

long, however, her friends note a marked deterioration in her clothing, physical

appearance, and manner of speaking. After three months, she ends up abandoned by her

protector (as was her fate at the end of the development section). Once again she has no

money. And now, more serious than her earlier beating by La Sanguijuelera, she must

endure having her beautiful face scarred forever by Gaitica’s knife.

Coda

Galdós’s last full chapter (II, xviii), excluding the narrator’s own two-sentence moraleja (II,

xix), constitutes his coda. Willi Apel and Ralph Daniel define the coda as a “concluding

passage or section, falling outside the basic structure of a composition, and added to

obtain or heighten the impression of finality” (62). The coda at the end of a sonata-form

composition traditionally emphasizes the A theme in order to demonstrate that, although

it was overshadowed at the end of the exposition and throughout the development

section, it has triumphed and has the right to a final statement. However, the A theme

itself, because of its constant contention and interplay with the B theme, has now ended

up being considerably changed also.

Such a change is certainly noticeable in Isidora in Galdós’s coda. In fact, as most critics

have noted, we have an entirely different protagonist at the end of the novel. However,

there is one illusion that she has not renounced: her belief that she deserves and needs

luxuries (“el delirio de las cosas buenas” [II, xvii: 473]). Consequently, when a

whoremongering procuress shows her the clothes that she can wear if she comes to work

for her (II, xviii: 481), these desired luxuries become a motivating factor for Isidora’s

opting for prostitution.

Recent criticism has emphasized other motivating factors, such as a desire for

independence or a need for self-expression. For example, Wifredo de Ráfols states:

Instead of committing suicide (an option she considers), she nullifies her

social identity and re-invents herself. Instead of accepting charity or any

number of offers of bourgeois economic security [. . .], she chooses

prostitution and the relative economic independence it promises.

[. . . Moreover, the] chapter title “Muerte de Isidora” represents not so

much Isidora’s moral suicide as an immoral homicide that is perpetuated

by an insane and unjust patriarchal society. Whether by suicide or

homicide, Isidora dies in name only. What dies with that name are her two

mutually irreconcilable lives, as well as the eponymous fiction to which

they gave rise (80-81).

Regardless of how one chooses to interpret Isidora’s final accommodation with the only

reality possible, considering her heredity and environment, I believe that another way of

stating the truth of the last sentence in the above quotation is to affirm that the novel’s

two competing themes, like two contending musical themes, are indeed literally and

figuratively at last played out. Isidora, with her unrelinquishable desire for luxuries, has

no recourse finally except to integrate herself into the harsh realities of prostitution. Then

Chamberlin 24

Galdós confirms, I believe, that the novel-long contention between the A and B themes is

now over by having the alcoholic José Relimpio, the last remaining active incarnation of

the A theme, expire. This action also allows the narrator to reiterate for a final time the

axis of the novel’s binary oposition: “Su muerte fue semejante a aquel dulce acceso de

embriaguez que le transportaba, mediante una breve toma, desde las miserias de la realidad a

las delicias de una vida apócrifa, compuesta con extraños fingimientos de juventud, pasión y

energía” (II, xxvii: 489, emphasis added).

As this study has demonstrated, Galdós did clearly follow the sonata form as he created

La desheredada, departing from it mainly to make volume I a self-contained, publishable

work in its own right. His artistry in La desheredada occurred nineteen years before he

openly acknowledged in Alma y vida that he followed “el plan y los módulos de la

composición beethoviana” (900). La desheredada also precedes by ten years Tristana, where

Galdós not only used the sonata-form structure, but also presented a character playing

Beethoven sonatas. Further study will be needed to determine whether or not specific

Beethoven sonatas can be identified as models for La desheredada and Tristana. In the

meantime, let us note that in both novels Galdós made no effort to conceal what he was

doing. In fact, in each he seems to be planting a playful clue (as he and other nineteenthcentury novelists were wont to do) concerning his creativity.

Why should La desheredada be the first in which Galdós chooses to pattern his novel after a

musical composition? We may never know for sure, but two factors should be considered.

The first is his friendship with fellow music lover Dr. Tolosa Latour, who, as is well

documented, served as the prototype for Miquis. It is possible that there may be some

inside, personal humor in La desheredada as Galdós amiably presents Miquis as a bumbling

sonata player. More importantly, it has been shown that Galdós simplified and sharpened

the delineation of important characters as he moved from his initial (Alpha) manuscript to

the final (Beta) version in order to make them stand in clearer opposition and apposition

(Schnepf, “Naturalistic Content” 53-60; Urey 5). Such a procedure produces characters

more conducive to the kind of interplay which is typical of musical themes in a sonata.

Moreover, critics agree that La desheredada marks a definite change from Galdós’s earlier

novels, that it is the first of his segunda época, and that it contains elements of Zolaesque

naturalism. For example, the same hereditary characteristics are shared by all the

members of the Rufete family: Isidora, her father, her uncle, her godfather, and her

brother. By making them all suffer varying degrees of mental illness and using them most

frequently to carry forward his initial A theme (which at the end of a work always turns

out to be the stronger), Galdós is able to effect in a very original way the naturalist’s

insistence on the inevitable consequences of negative heredity. Critics tend to agree that

Galdós’s naturalism is softer, “more mitigated” than Zola’s (Pattison 63). An important

key to a deeper understanding of this achievement (as Galdós moved away from the very

strong naturalism of his Alpha manuscript)15 may lie in the interrelationship between

Galdós’s love of music and his novelistic creativity.

UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS

Chamberlin 25

Notes

For such demonstrations, see Chamberlin, “Sonata Form” (83-96) and Galdós and

Beethoven (21-48).

2 This point is established in Aronson (66), Cluck (153-224), and Burgess (Personal

Interview, 19 October 1977).

3 This numeration includes one-line sentences in conversations, as well as the usual

definitions of a paragraph.

4 In 1974, Frank Durand correctly identified the novel’s two major themes as illusion and

reality, “which involve an alternating and fluctuating movement [. . . from one to the

other].” However, he makes no mention of music or musical structure (191-201).

Also, Robert Russell has pointed out a structural similarity concerning the initial

ascent and subsequent descent of the protagonist in La desheredada and the typical

naturalist novel (794-800). Again there is no mention of music or musical structure.

5 The numbers in parenthesis refer to volume, chapter, section (when applicable), and

page.

6 Eamonn Rodgers finds Galdos’s description of the rope factory much like the naturalist

“set piece” descriptions of industrial conditions in the late nineteenth-century (70).

One of the best-known examples would be the foundry where Gervaise’s son,

Etienne, works in Zola’s L’Assommoir (I, vi: 205-222).

7 These chapters have been discussed by Stephanie Sieburth (67-76) and Martha KrowLucal (20-31). Neither makes any mention of musical structure or sonata form.

8 The narrator says, “La cama dorada de la alcoba permanecía como núcleo y

fundamento de la casa” (II, ii, 3: 279). For the symbolic connotations of the bed, as

well as those of other furnishings in Isidora’s house, see Wright (230-45).

9 Here is the narrator’s complete statement: “Parece que la Naturaleza quiso hacer en

aquella pareja sin ventura dos ejemplares contrapuestos de moral desvarío, pues si ella

vivía en una inspiración insensata a las cosas altas, poniendo como dice San Agustín,

su nido en las estrellas, él se inclinaba por instinto a las cosas groseras y bajas” (II, iv,

1: 289).

10 I am indebted to Anthony Burgess, author of the novel Napoleon Symphony, for

confirmation of this opinion (personal interview, 2 November 1975; class lecture).

11 For the political and financial scandals associated with the construction of this

establishment, and Galdós’s interest in them, see Schnepf, “Scandal” (36-49).

12 For the terrible conditions in this particular prison in the 1880s, including bribery,

prostitution, and exploitive lesbianism, see Schnepf, “Scandal” (36-49).

13 In consonance with the fact that the recapitulation section in the music of a sonata

form is shorter than the development section, Galdós reduces the number of Isidora’s

lover/protectors from four to one.

14 For the newly-acquired importance of the baño in late nineteenth-century Spain, see

Fernández Cifuentes (363-83).

15 For an appreciation of how Galdós also toned down or “mitigated” the stark naturalism

of his own preliminary version of La desheredada, see Schnepf, “Naturalistic Content”

(53-59) and “Creation” (61-65).

1

Chamberlin 26

Works Cited

Aronson, Alex. Music and the Novel: A Study in Twentieth Century Fiction. Totowa, NJ:

Rowman and Littlefield, 1980.

Apel, Willi and Ralph Daniel. The Harvard Brief Dictionary of Music. Cambridge: Harvard

UP, 1966.

Burgess, Anthony. Class lecture. 19 October 1977.

---. Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements. New York: Knopf, 1974.

---. Personal interview. 2 November 1975.

---. Personal interview. 19 October 1977.

Chamberlin, Vernon. “The Sonata Form Structure of Tristana.” Anales Galdosianos 20.1

(1985): 83-96; rpt. “The Perils of Interpreting Fortunata’s Dream” and Other Studies in

Galdós: 1961-2002. Newark, DE: Juan de la Cuesta, 2002. 259-72.

---. Galdós and Beethoven: Fortunata y Jacinta, A Symphonic Novel. London: Tamesis, 1977.

Cluck, Nancy Anne. Essays on Form: Literature and Music. Provo: Brigham Young UP, 1981.

Durand, Frank. “The Reality of Illusion: La desheredada.” MLN 89 (1974): 191-201.

Fernández Cifuentes, Luis. “Galdós y las arquitecturas del asedo.” Letras Peninsulares 13.1

(2000): 363-83.

Krow-Lucal, Martha. “The Marquesa de Aransis: A Galdosian Reprise.” Essays in Honor

of Jorge Guillén on the Occasion of his Eighty-fifth Year. Cambridge, MA: Abedul, 1977.

20-31.

Pattison, Walter. Benito Pérez Galdós. Boston: Twayne, 1975.

Pérez Galdós, Benito. Alma y vida. Obras completas. Ed. F. C. Sáinz de Robles. 2ª ed. Vol.

VI. Madrid: Aguilar, 1951.

---. La desheredada. Ed. Enrique Miralles. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991.

---. Tristana. Obras completas. Ed. F. C. Sáinz de Robles. 3ª ed. Vol. V. Madrid: Aguilar,

1961.

Ratner, Leonard G. Music: The Listener’s Art. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1966.

Rodgers, Eamonn. From Enlightenment to Realism: The Novels of Galdós: 1870-1887. Dublin:

[E. Rodgers], 1987.

Russell, Robert H. “The Structure of La desheredada.” MLN 76 (1961): 794-800.

Schnepf, Michael. “From Galdós’s La desheredada Manuscript: Male Characters in

Transition.” Romance Quarterly 39 (1992): 53-60.

---. “On the Creation and Execution of ‘Pecado’ in Galdós’s La Desheredada.” Anales

Galdosianos 34 (1999): 61-68.

---. “Scandal and La Cárcel Modelo: More Intertextual ‘Bouncing’ in Galdos’s La

desheredada.” Romance Quarterly 49 (2002): 36-49.

---. “The Naturalistic Content of the La desheredada Manuscript.” Anales Galdosianos 24

(1989): 53-59.

Sieburth, Stephanie. Inventing High and Low: Literature, Mass Culture, and Uneven Modernity in

Spain. Durham: Duke UP, 1994.

Sopeña Ibáñez, Federico. Arte y sociedad en Galdós. Madrid: Gredos, 1970.

Urey, Diane F. Galdós and the Irony of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1982.

Verdaguer, Mario. Medio siglo de la vida Barcelonesa. Barcelona: Barna, 1975.

Chamberlin 27

Wright, Chad G. “The Representational Qualities of Isidora Rufete’s House and Her

Son Ruiquín in Pérez Galdós’s La desheredada.” Romanische Forschungen 83 (1971): 23045.

Zola, Emile. L’Assommoir. Paris: Bibliotheque-Carpentier, 1925.