Thesis_Report_NMPereira_OnlineVersion_Final

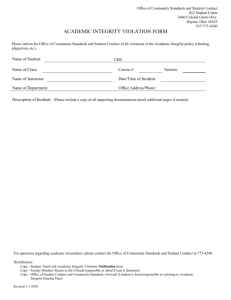

advertisement