Integrated Food Security and Humanitarian Phase Classification

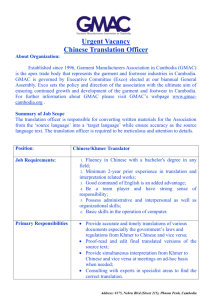

advertisement