Document

advertisement

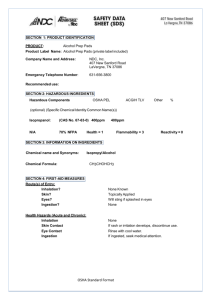

Topic 2 Legal Requirements LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of this topic, you should be able to: 1. Explain how legislations are enacted; 2. Connect the law with safety objectives; 3. Describe the fundamental concepts of OSH legislation; and 4. Differentiate between the role of authority and the role of industry. INTRODUCTION Legislative framework plays a significant role in ensuring the progress of safety practices in any country. Without the governmentÊs initiatives, occupational safety and health (OSH) will not become a national agenda. Laws and regulations are not made for the sake of copying other countries. They are made by the government to protect the people. In this case, the protection in place is for the well-being of the workforce. 2.1 STATUTE LAW AND COMMON LAW The law concerning safety and health is a combination of statute law and common law. This section will explain statute law and common law as well as the difference between the two. 2.1.1 Statute Law Statute law is the written law of a country consisting of Acts of Parliament, regulations and orders made within the parameters of a relevant subject in focus. TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 19 These Acts usually set out a framework of principles in the areas or issues involved. In order to achieve the objectives, Acts are supported by regulations and orders. Regulations and orders are not necessarily written at the time the Acts were introduced. They are sometimes added in after the Acts are established to accommodate new requirements. 2.1.2 Common Law Common law has evolved over the years as a result of decisions by courts and judges. The sector of common law related to OSH issues is known as tort of negligence. Some literature refers to it as Law of Tort. A tort is defined as a type of civil offence. This is where the common principles fill the gap if and when a statute law does not supply any specific requirements. For instance, the relationship between an employer and the employees is a special application of common law principles. Employers are responsible for the well-being of their workers in their working environment. Employers are also liable for the actions of their employees that cause injury, death or damage to others. This form of liability of the employer is known as vicarious liability. 2.1.3 Differences between Statute Law and Common Law There are two essential differences between statute law and common law. They are: There is a penalty provided for a breach of a statute law regardless whether damage or loss has occurred or not; and By common law, actions are decided only if there is damage or loss. 2.2 2.2.1 RELEVANT DOCUMENTS IN PRACTICE Industry Codes of Practice (ICOP) An ICOP supports Acts and regulations which are in place and also serves as a guideline on the general requirements set out in the legislation. Through its application, ICOP enables legislation to be kept up to date by revising the ICOP rather than the law. ICOP can be used in proceedings. 20 2.2.2 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Guidelines Guidelines are documents that present opinions on good practice. One may apply what is suggested in the guide in his/her workplace. Guidelines have no legal force. However, because they are developed based on industrial experience, they are persuasive in practice to the lower courts and in civil cases to establish reasonable safety standards (Holt, 2006). Locally, the Department of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH) is a good source for published ICOPs and Guidelines. 2.3 2.3.1 STATUTORY DUTY Acts and Regulations: Basic Knowledge The Act – Upon ParliamentÊs Approval and KingÊs consent. The Regulation – Upon Relevant MinistriesÊ Approval 2.3.2 Main Legislative References There are two main references involving OSH in Malaysia: (i) Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994, Act 514. (OSHA 1994) (ii) Factories and Machinery Act 1967, Act 139. (FMA 1967) Apart from these two Acts, there are also other applicable or related Acts on construction and plant safety, namely: (i) Explosive Act 1957. (ii) Social Security Act 1969. (iii) Environmental Quality Act 1974. (iv) Street Drainage and Building Act 1974. (v) Destruction Disease Bearing Insect Act 1975. (vi) Town and Country Planning Act 1976. (vii) Uniform Building By-Laws 1984. (viii) Fire Service Act 1988. (ix) Electrical Supply Act 1990. TOPIC 2 (x) LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 21 Construction Industrial Development Board (CIDB) Act 1994. (xi) Waters Act 1920. (xii) Forestry Act 1984. (xiii) Other Acts – which may depend on actual activities or location. Once a safety regulation is enforced, it means statutory obligation for those involved. Clauses with the word „shall‰ are indication that the particular items are absolute duty, also known as strict liability. Some of the clauses are straightforward, directly focusing on behaviour compliance or physical compliance as in the following examples: It shall be the duty of every employee while at work to wear or use at all times personal protective equipment (PPE). (Part VI, Section 24(c), OSHA 1994) Every stairway opening except at the entrance thereto shall be fenced on every exposed side by guard rails and toe-boards. (Reg8 (2), FM (Safety Health & Welfare) Regulations 1970.) However, not all situations can have clear cut instructions like the examples given as designs and work processes are becoming more complex. However, the constant focus or primary objective in any working environment should always be „safety first‰. Consequently, a question may be posed, „To what extent are safety practices or control measures required?‰ This question is raised due to the wide range of activities plus varied scenarios in the construction industry. Imagine and blend all these together: time constraints, space constraints, fancy designs, different works at the same time, different works at the same area, works over water and so on. These are all elements in a construction industry that affect the safety and well-being of workers. Responding to the above question, Part IV, Section 15(1) of OSHA 1994 clarifies: „It shall be the duty of every employer and every self-employed person to ensure, so far as is practicable, the safety, health and welfare at work of all his employees.‰ 22 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS OSHA 1994 further elaborates „so far as is practicable‰ with these considerations: The severity of the hazard or risk in question; The state of knowledge about the hazard or risk and any way of removing or mitigating the hazard or risk; The availability and suitability of ways to remove or mitigate the hazard or risk; and The cost of removing or mitigating the hazard or risk. ACTIVITY 2.1 Explore DOSHÊs website where you can find Codes of Practice and Guidelines and other useful information. You can also download standard forms used in dealing with DOSH. Share your findings with your classmates. SELF-CHECK 2.1 1. What is „vicarious liability‰? 2. What are the differences between „statute law‰and „common law‰? 3. ‰So far as is practicable‰ is typified with certain conditions. What are these conditions we need to consider? 2.4 REASONABLY PRACTICABLE VERSUS PRACTICABLE In order to understand the requirements by legislation, you must first understand these expressions: So far as is reasonably practicable So far as is practicable In Great Britain, Health and Safety Executive (HSE), an independent regulator which acts in the public interest to reduce work-related death and serious injury across Great BritainÊs workplaces, proposes that both expressions are not defined TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 23 in the United KingdomÊs Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, but they have required meanings through many interpretations by the courts (HSE, 1997). 2.4.1 So Far as is Reasonably Practicable To carry out a duty ‰so far as is reasonably practicable‰ means that the degree of risk can be balanced against the time, trouble, costs and physical difficulty of taking the measures to counter the risks (Health and Safety Guidance 65 (HSG65), n.d.). 2.4.2 So Far as is Practicable To carry out a duty ‰so far as is practicable‰ without the word ‰reasonably‰, refers to a stricter standard compared with ‰reasonably practicable‰. ‰So far as is practicable‰ generally embraces whatever is technically possible. Also taken into consideration is the current knowledge which the person concerned has, or ought to have had at that particular time. In the ‰so far as is practicable‰ case, the trouble, time and costs are not to be taken into account as considerations (HSG 65, n.d.). If we study the above view, HSG65Ês interpretation of ‰so far as is practicable‰ is strict where the cost and other factors are immaterial. Thus, if we compare HSG65Ês views with OSHA 1994, we may assume that OSHA 1994 is a bit more flexible. It operates between the range of ‰reasonably practicable‰ to ‰practicable‰. This is because in OSHA 1994, ‰so far as is practicable‰ also regards the costs involved. It allows employers to conduct a cost benefit analysis. (Rozanah, 2005). From the legal perspective, the final decision is for the court to decide whether actions taken by an employer achieved ‰so far as is practicable‰ or not. 2.5 OVERVIEW OF OSHA 1994 AND FMA 1967 The existing laws governing plant and construction safety as well as occupational safety and health (OSH) were not created overnight. Hopefully, by going through the history of the development of OSHA 1994 and FMA 1967, you will gain a better appreciation of the legislation governing plant and construction safety. 24 2.5.1 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Development of Local OSH Legislation The Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (FMA 1967) was enacted in 1967. Since the Act was enacted in the late 1960s, FMA 1967 might seem to be the earliest Act concerning OSH in Malaysia. As a result, some might mistakenly think that OSH legislations in Malaysia were only practiced or introduced in the late 1960Ês. This assumption is incorrect. In reference to past records, FMA 1967 has its origin from as early as 1876. Today, FMA 1967 is closely connected with the construction industry. One of the important references for construction found in FMA 1967 is known as Building Operations and Works of Engineering Construction Safety Regulations 1986 or in short, BOWEC. Beginning as a simple rule to regulate the use of steam boilers, FMA 1967 evolved into a more comprehensive legislation to cater to the complex OSH problems prevailing today (Rozanah, 2009). The following is a chronology of the earlier legislations that evolved into FMA 1967: Steam Boilers Ordinance 1876 (Straits Settlements) Steam Boilers Ordinance 1887 (Straits Settlements) Machinery Ordinance 1921 (Straits Settlements) Selangor Steam Boilers (Ashore) Inspection Regulations 1893 (Federated Malay States) Selangor Boilers Enactment 1898 (Federated Malay States) Steam Boilers Enactments of the states of Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang 1908 (Federated Malay States) Machinery Enactment 1913 (Federated Malay States) Machinery Enactment 1927 (Federated Malay States) Machinery Enactment 1932 (Federated Malay States) Machinery Ordinance 1953 (Federation of Malaya) Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (Malaysia) Occupational Safety and Health Act. 1994 (Malaysia ) Factories and Machinery Act (Amendment) 2006 (Malaysia) There are also records of the first oil well discovered in 1910 in Miri, Sarawak. Later in 1914, a refinery plant was built (M. Sha, 1996). There were also records regarding the management of health and safety of workers involved in these operations. TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 25 From the evolution in the legislation concerning OSH, we can safely say that occupational safety and health is not a new concern in Malaysia and the legislations on OSH in Malaysia are developed, enacted and amended from time to time to ensure that they keep up with the changes in the industry. 2.5.2 Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994 (OSHA 1994) „Those who produced hazards are those responsible to manage hazards.‰ OSHA 1994 adopts the ‰Self Regulations Concept‰. However, it is important not to confuse ‰self regulations‰ with Âself-styledÊ approaches in managing hazard. ‰Self-regulation‰ provides freedom for the employers to plan and decide on how to manage their hazards. Self-regulating practices may exceed or operate within the scope of ActsÊ requirements. In order to achieve the end objective, consultation and workersÊ involvement are also part of OSHA 1994Ês philosophy. The OSHA 1994 principle legislations are supported by rules, regulations and orders. Generally, it is not necessary for the supporting regulations to be created in the enactment year itself. Therefore in OSHA 1994, you will find rules, regulations or orders with the indication of the year it was established. The term ‰OSHA mother act‰ is another name for OSHA 1994, specifically in its basic form. OSHA 1994 „grew up‰ and „gave birth‰ to other related items such as rules, regulations, orders or even schedules. As mentioned earlier, only ministriesÊ approval are needed for all follow-up or new regulations. 2.5.3 Objectives of OSHA 1994 The objectives of OSHA 1994 (Act 514) are: To secure the safety, health and welfare of persons at work; To protect others against risks to safety and health in connection with the activities of persons at work; To promote occupational environment adaptable to the persons physiological and psychological needs; and To provide the means towards a legislative system based on regulations and industry codes of practice in combination with the provisions of the Act. 26 2.5.4 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Arrangement of OSHA 1994 This section shows the structure of OSHA 1994. OSHA 1994 is arranged in the following sequence: Part I – Preliminary Part II – Appointment of Officers Part III – National Council for Occupational Safety and Health Part IV – Duties of Employers and Self Employed Persons Part V – General Duties of Designers, Manufacturers and Suppliers Part VI – General Duties of Employees Part VII – Safety and Health Organisations Part VIII – Notification of Accidents, Dangerous Occurrence, Occupational Poisoning and Occupational Diseases, and Inquiry Part IX – Prohibition Against Use of Plant or Substance Part X – Industry Code of Practice Part XI – Enforcement and Investigation Part XII – Liability for Offences Part XIII – Appeals Part XIV – Regulations Part XV – Miscellaneous 2.5.5 Regulations and Orders Under OSHA 1994 As mentioned earlier, OSHA 1994 is also known as the ‰OSHA mother act‰. This „mother act‰ has ‰given birth‰ to the following regulations and order: 1996 – Control of Industrial Major Accident Hazards Regulations 1996; 1996 – Safety and Health Committee Regulations 1996; 1997 – Classification, Packaging and Labelling of Hazardous Chemicals Regulations 1997; 1997 – Safety and Health Officer Regulations 1997; 1997 – Safety and Health Officer Order 1997; TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 27 1999 – Prohibition of Use of Substance Order 1999; 2000 – Use and Standards of Exposure of Chemicals Hazardous to Health Regulations 2000; and 2004 – Notification of Accident, Dangerous Occurrence, Occupational Poisoning and Occupational Disease Regulations 2004. 2.5.6 Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (FMA 1967) In Malaysia, prior to OSHA 1994 enactment, FMA 1967 was the sole OSH legislative reference pertaining to industriesÊ activities. However, FMA 1967 was not comprehensive enough to cover all industries and was quite descriptive and rigid in some way. Not all technical details in FMA 1967 were applicable to all situations. Eventually, OSHA 1994 was enacted as the specific legislation to govern safety and health of all employees at all workplaces (Rozanah, 2009). 2.5.7 Objectives of FMA 1967 The objectives of FMA 1967 (Act 139) are: To provide for the control of factories with respect to: matters relating to the safety, health and welfare of persons therein; the registration and inspection of machinery; and matters connected therewith. 2.5.8 Arrangements of FMA 1967 This section shows the structure of FMA 1967. FMA 1967 is arranged in the following sequence: Part I – Preliminary Part II – Safety, Health and Welfare Part III – Persons in Charge and Certificate of Competency Part IV – Notification of Accident, Dangerous Occurrence and Dangerous Disease Part V – Notice of Occupation of a Factory, and Registration and Use of Machinery Part VI – General 28 2.5.9 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Regulations Under FMA 1967 There are fifteen regulations under FMA 1967. They are: (i) Steam Boiler and Unfired Pressure Vessel, Regulations 1970. (ii) Electric Passenger and Goods Lift, Regulations 1970. (iii) Fencing of Machinery and Safety, Regulations 1970. (iv) Persons-In-Charge, Regulations 1970. (v) Safety, Health and Welfare, Regulations 1970. (vi) Administration, Regulations 1970. (vii) Certificates of Competency-Examinations, Regulations 1970. (viii) Notification, Certificate of Fitness and Inspection, Regulation 1970. (ix) Compoundable Offences, Regulations 1978. (x) Compounding and Offence, Rules 1980. (xi) Lead, Regulations 1984. (xii) Asbestos Process, Regulations 1986. (xiii) Building Operations and Works of Engineering Construction (Safety), Regulations 1986. (xiv) Noise Exposure, Regulations 1989. (xv) Mineral Dust, Regulations 1989. In 2006, FMA 1967 was amended. The new changes included those related to the definition of ÂfactoryÊ, regarding licensed person, certificate of fitness, revised fees, notification of accident and a few others. Penalties and imprisonment terms were also increased. In this amendment, the maximum penalty that can be imposed stands at RM250,000 and maximum imprisonment term of up to five years. The amendment involves 30 provisions including the introduction of new provisions into the FMA 2006 (Rozanah, 2009). However, even with these changes, the core contents and structure of FMA 1967 generally remain as their original form. TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 29 ACTIVITY 2.2 FMA 1967 was first enacted in 1967. Then in 1994, OSHA 1994 was enacted. The general rule is, Âfor any same issue referred, OSHA 1994 supercedes FMA 1967.Ê The reason is the latest legislation supercedes the previous. Now with the presence of FMA 1967 Amendments 2006, is there any possibility of FMA superceeding OSHA? Discuss. SELF-CHECK 2.2 1. What is „reasonably practicableÊÊ? 2. List OSHA 1994 objectives. 3. List FMA 1967 objectives. 2.6 PRACTICAL COMPLIANCE Practical compliance may range from behaviours and documentations to physical compliances. The complete discussion on practical compliance covers many different aspects. However, in this subtopic, we will only discuss aspects that are considered as most appropriate. Some explanations are also summarised accordingly for easier memory retention. Thus, for an in-depth elaboration on the subject of practical compliance, you are strongly advised to refer directly to OSHA 1994, FMA 1967 or other sources discussing legislative issues in-depth. 2.6.1 Duties of Employer and Self-Employed Persons For a clearer view on the duties of employers towards their employees, you can refer to Section 15 OSHA 1994 while Section 17 explains employersÊ duties towards those other than their employees. The duties include to: Provide and maintain safe plant and system of work; Make arrangements for safe use, operation, handling, storage and transportation of plant and substances; 30 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Provide instruction, information, training and supervision; Provide and maintain safe place of work and means of access to and egress from any place of work; Provide and maintain safe and healthy working environment and adequate welfare facilities; and Provide safety and health protection and also relevant information as necessary to other persons, not being their employees. A maximum penalty of RM50,000 or 2 years imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.2 Duties of an Occupier of a Place of Work According to Section 18 OSHA 1994, the duties of an occupier of a place or work are to: Provide safe access and egress Ensure safe use of plant and substance Include public safety – Regulations 39(1), FMA (Safety, Health and Welfare) Regulations 1970. A maximum penalty of RM50,000 or 2 years imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.3 Duties of Employees According to Section 24 OSHA 1994, the duties of employees are to: Cooperate with employers. Practise reasonable care for safety and health on himself and others. Wear and use personal protective equipment (PPE). Comply with instruction on OSH. A maximum penalty of RM1,000 or 3 months imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. Note: Employers are not allowed to employ persons less than 16 years old. For more information on ‰young persons‰, you can refer to Section 28, Pt. III FMA 1967 and Section 28(c), Pt. VII OSHA 1994. TOPIC 2 2.6.4 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 31 Duties of Designers, Manufacturers and Suppliers According to Section 21 OSHA 1994, the duties of designers, manufacturers and suppliers are to: (a) Ensure substance is safe and without risks to health when properly used; (b) Carry out or arrange for the carrying out of such testing and examination as may be necessary for the performance of the duty imposed on him by (a); and (c) Provide adequate information. A maximum penalty of RM20,000 or 2 years imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.5 Formulation of Safety and Health Policy (Section 16 OSHA 1994) (subject to condition: if 5 or more employees) A maximum penalty of RM50,000 or 2 years imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.6 Establishment of Safety and Health Committee (Section 30 OSHA 1994) (subject to condition: if 40 or more persons employed) A maximum penalty of RM5,000 or 6 months imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.7 Appointment of Safety and Health Officer (Section 29 OSHA 1994) (subject to condition: if project cost is more than RM20 million) A maximum penalty of RM5,000 or 6 months imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 32 2.6.8 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Notification of Accident, Dangerous Occurrence, Occupation Poisoning and Occupational Disease (NADOPOD) (Section 32 OSHA 1994) (For cases as specified in the NADOPOD Regulations, please refer to First Schedule-Serious Bodily Injury; Second Schedule-Dangerous Occurrence and Third Schedule-Occupational Poisoning and Disease. Also refer to FMA Pt IV, Sect. 31. And, FMAÊs First Schedule-Dangerous Occurrence, Second Schedule-Serious Bodily Injury and Third ScheduleIndustrial Disease) A maximum penalty of RM10,000 or 1 year imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.9 Cooperation to Investigation/Inspection Officers (Section 47 OSHA 1994: Offences in Relation to Inspection) Owner or occupier or employer of any place of work need to provide assistance for any: Entry Inspection Examination Inquiry A maximum penalty of RM10,000 or 1 year imprisonment or both can be imposed for non-compliance. 2.6.10 Regarding Improvement Notice and Prohibition Notice (Section 48 OSHA 1994) In practice, enforcement authority usually issues NOI (Notice of Improvement) or NOP (Notice of Prohibition) for any non-compliance found at the site. Once an NOI or NOP is issued, the employer is expected to take necessary corrective actions within a stipulated period. – Sometimes, an NOP is also referred to as a Stop Work Order: TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 33 Penalty for failure to comply with notice: Maximum RM50,000 or maximum 5 years imprisonment or both and RM500 per day for continuous offence. 2.6.11 General Penalty In the examples above, there are specific requirements with specific penalties mentioned. However, not all offences can be pointed out in detail. What if one is found guilty for an offence, but there is no specific penalty provision for it? The answer is General Penalty (Part XII Section 51, OSHA 1994). Fine not exceeding RM10,000 or imprisonment not exceeding 1 year or both and fine of RM1,000 per day for continuing offence. What does this mean? It means any unsafe practice is always an offence, with the possibility of conviction. In conclusion, all safe practices are practical compliances. 2.7 POWER OF ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS As mentioned earlier, enforcement officers may issue improvement notice or stop work order for any non-compliance discovered. That is only a small part of the enforcement authority. 34 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Below are Sections from OSHA 1994 relating to the power of enforcement officers: Table 2.1: Power of Enforcement Officers According to OSHA 1994 Section in OSHA Enforcement Authority Section 34 Regarding power of officer at inquiry. The officer can be vested with powers of First Class Magistrate. Section 35 Regarding power to prohibit the use of plant or substance Section 39 Regarding power of entry, inspection, examination, seizure, etc. Section 40 Regarding entry into premises with search warrant and power of seizure. Section 41 Regarding entry into premise without search warrant and power of seizure. Section 42 Regarding power of forceful entry. Section 44 Regarding power of investigation. Section 45 Regarding power to examine witness. Section 48 Regarding NOI and NOP. Section 48 to Section 61 Regarding prosecutions. Summarising the above, the officers can: Gain access without warrant to a workplace at any time. Employ the police to assist in the execution of the duty. Bring in equipment or materials into the premise to assist investigations. Carry out necessary examinations and investigations. Direct that location remain undisturbed for as long as is seen fit. Take measurements, photographs and samples. Order the removal and testing of equipment. Take articles or equipment out for further testing. Take statements, records and documents. Require other facilities or assistance which may be needed (Holt, 2006). TOPIC 2 2.7.1 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 35 Occupational Safety and Health Officer versus. Safety and Health Officer (SHO) Enforcement Officers are DOSH personnel who are appointed under Section 5(2) OSHA 1994. They are ‰Occupational Safety and Health Officer/s‰, and are referred to as ‰officer‰ in the Act. This „officer‰ interpretation includes the Director General, Deputy Directors General, Directors, Deputy Directors and Assistant Directors of DOSH. Meanwhile „Safety and Health Officer/s‰ are those who are appointed in relation with Section 29 and Section 66(2) (t) OSHA 1994 and they are hired by industries. To distinguish between these two officers, remember that one is an „occupational‰ officer while the other is not. 2.7.2 Safety and Health Officer As mentioned above, SHOs are hired by industries. There is a special clause about the hiring or employing of a Safety and Health Officer. In Section 29(3) it states that: „The safety and health officer shall be employed exclusively for the purpose of ensuring the due observance at the place of work of the provisions of this Act and any regulation made thereunder and the promotion of a safe conduct of work at the place of work.‰ In accordance with Section 18, SHO Regulations 1997, the job specifications of an SHO as outlined in the Act are: Advise the employer or any person in charge, regarding safety and health. Safety and health inspections of the place of work including equipment, process, substance and others which may affect the safety and health of workers. Investigate any incident. Assist the employer or Safety and Health Committee regarding OSH. As Secretary of Safety and Health Committee (SHC). Assist SHC in any safety inspection, effectiveness and efficacy of safety measures taken in compliance with the Act. 36 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS To collect, analyse and maintain safety statistics on accident, dangerous occurrence, occupational poisoning and occupational disease occurring at the workplace. Assist any officer in carrying out his/her duty under the Act or in the regulations under the Act. To carry out other instructions made by employer on any matters pertaining to safety and health. 2.8 FMA 1967 OVERVIEW Studying the ‰mother act‰Ê is helpful in understanding the birth of subsequent regulations. This applies to both – OSHA 1994 and FMA 1967. In the FMA mother act, there are three important components which were later supported by their respective regulations. They are: Safety, Health and Welfare (SHW) in Part II. Persons in Charge and Certificate of Competency in Part III. Notice of Occupation of Factory, and Registration and Use of Machinery in Part V. 2.8.1 Safety, Health and Welfare Among the issues mentioned in SHW are: Safety of workers regarding physical hazards due to unsafe condition Safety of workers regarding hazards due to machine or equipment (i.e. machinery as a potential root cause or latent cause of an accident) Fire hazard Health issues and even an ergonomic issue (please refer to Section 12) PPE , welfare and facilities issues PersonÊs Certificate of Fitness/Competency of employee (please refer to Section 19). TOPIC 2 2.8.2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 37 Persons in Charge and Competency This section concerns the credibility of persons allowed to carry out certain responsibilities and tasks. It focuses on the competency and certification of a person and also prohibits certain machines to be operated without certificated staff (as in Section 29). 2.8.3 Notification of Occupation of Factory, and Registration and Use of Machinery This section is about matters pertaining to procedures prior to any industrial operation. Those who are involved are required to fulfil and adhere with all stipulated requirements before they are allowed to begin operations. 2.9 ADMINISTRATION AND PROCEDURES COMPLIANCE There are several administrative procedures that has to be followed when dealing with OSH authorities. The following subtopic highlights the procedures as well as documentation required for the related activities. 2.9.1 Application Procedures: DOSH Forms The following are the related DOSH forms and its function: JKJ 101 – Notice of first occupation or use of any premise as factory under Section 34(2) (a) FMA. JKJ 102 – Notice in respect of taking over of a factory under Section 34(2) (b) FMA. JKJ 103 – Notification of Building Operations and Works of Engineering Construction under Section 35(1) FMA. JKJ 105 – Application for permission to install machinery under Section 36(1) FMA and issue Certificate of Fitness in respect of steamboiler, unfired pressure vessel or hoisting machine, not hoisting machine driven by manual power. JKJ 106 – Notice of first use of machinery other than the machinery for which a Certificate of Fitness is prescribed as required under Section 36(3) FMA. 38 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Note: For JKJ 103, there is no need to submit notification if operation is less than 6 weeks and no machinery is used (Section 35(2) FMA). And the term ‰machinery‰Ê is as defined in FMA. 2.9.2 NADOPOD Procedures: DOSH Forms The following are the related DOSH forms related to NADOPOD procedures and its function: JKKP 6 – Notification of Accident/Dangerous Occurrence JKKP 7 – Notification of Occupational Poisoning/ Occupational Disease JKKP 8 – Register of Accident, Dangerous Occurrence, Occupational Poisoning and Occupational Disease JKKP 9 – Notification of Accident/Dangerous Occurrence: Data and Description JKKP 10 – Notification of Occupational Poisoning/Occupational Disease: Data and Description 2.9.3 CIDB Greencard Compliance In accordance with 2001 CIDB Circular 1/2001, all personnel working at the construction site need to possess the Greencard. Without a Greencard, one is not allowed to work at a construction site. A Greencard is to indicate a person has attended a specially designed Safety and Health course for the constructionÊs environment. In this Greencard system, CIDB categorised ‰Construction Personnel‰ as: General Worker Semi-Skilled Worker Skilled Worker Supervisor, Clerk of Work, Site Agent or equivalent Site Manager, Site Engineer or equivalent Quality Assurance, and Any other categories classified by CIDB from time to time. TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 39 2.10 BUILDING OPERATIONS AND WORKS OF ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION (BOWEC) The official title for this regulation is the Factories and Machinery (Building Operations and Works of Engineering Construction) (Safety) Regulations, 1986. It is commonly referred to as BOWEC. BOWEC Regulations are quite comprehensive as they cover almost every activity or item you can find in a constructionÊs environment. Therefore, not all requirements are covered here. Below is only the overview, and selected and condensed information. Some relevant and important issues will be discussed in the next topic. 2.10.1 Arrangement of Regulations Part I – Preliminary Part II – General Provisions Among the provisions are: Physical hazards including drowning; Tool and electrical hazards; Health hazards; Safe walkways; PPEs; Waste Disposal; Safety Personnel; and Safety Committee. Part III – Concrete Work Among the provisions are: Professional Engineer (P.E.) designed formwork and reshores; Inspections of formworks; and Formwork stripping. 40 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Part IV – Structural Steel and Precast Concrete Assembly Among the provisions are: Instructions on safe methodology; Taglines; and Temporary flooring. Part V – Cleaning, Repairing and Maintenance of Roof, Gutters, Windows, Louvres and Ventilators Among the provisions are: Work on steep roof; Roofing brackets; and Crawling board dimensions. Part VI – Catch Platforms Among the provisions are: P.E. Designed; Dimensions and minimum load capacity; and Details to conform with Code of Practice for Building Operation Code Part VII – Chutes, Safety Belts and Nets Among the provisions are: Provision on construction of chute. (If more than 12 metres, need P.E. Design); Life lines and safety belts; and Storage and inspections. Part VIII – Runways and Ramps The provisions are mainly regarding dimensions according to users. (i.e. vehicles, employees or wheel-barrow) Part IX – Ladders and Step-Ladders Among the provisions are regarding secured footing and handhold. TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 41 Part X – Scaffolds Among the provisions are: P.E. Design for metal tube scaffold exceeding 40 metres P.E. Design for other scaffold exceeding 15 metres Inspections by a competent person Supported by building Working platform safety Construction of tubular scaffold Part XI – Demolition A very important requirement is that during demolition, continuing inspections by a designated person as the work progresses to detect any hazard due to weakened floors or walls or loosed materials. Part XII – Excavation Work A very important requirement is that excavation site and its vicinity shall be checked by a designated person after every rainstorm or other hazard-increasing occurrence. Part XIII – Material Handling and Storage, Use and Disposal The provisions are mainly regarding safe method, requirement and dimensions. Part XIV – Piling One of the requirements is daily inspection by a designated person before start of work. Part XV – Blasting and Use of Explosives Among the provisions are: Designated person Safe handling of explosives Audible warning before blasting Part XVI – Hand and Power Tools Regarding various tools s such as Electric/Pneumatic/Fuel/Hydraulic-powered tools, hand tools and power-actuated tools. 42 TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITY 2.3 As far as legislation is concerned, all regulations are important. But why did we not discuss CIMAH Regulations 1996 (Control of Industrial Major Accident Hazards) in this module? Think about it. Statutory duty is a must-do duty. So far as is practicable is whatever is technically possible. All safe practices are practical compliance. Mother act gives the concept and directions, regulations give details. BOWEC is an important reference for construction activities. Absolute duty FMA and OSHA Acts and Regulations Mother act BOWEC Practicable Compliance Statutory TOPIC 2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 43 1. List the duties of an employer. 2. List three powers of Enforcement Officers. 3. List three duties of an SHO. 4. Explain briefly the development of local OSH legislation. 5. Describe the „Self Regulation Concept‰ in OSHA 1994. 6. Explain the duties of employees in Section 24, OSHA 1994. 7. Explain briefly the difference between „Occupational Safety and Health Officer AND Safety and Health Officer (SHO)‰. 8. List five (5) categorised „Construction Personnel‰ as in the „CIDB Green Card Circular – 1/2001‰. FMA 1967 Holt, A.S.J., (2006). Principles of Construction Safety. Oxford: Blackwell. HSG65, (1997). Successful Health and Safety Management. UK: HSE. M. Sha, J., (1996) in Occupational Safety and Health in Malaysia. NIOSH Malaysia: 1996. (Compilation of Articles. Edited by Krishna Gopal Rampal & Noor Hassim Ismail.) OSHA 1994 Rozanah, A.R., (2005). Duty to Provide Safety and Health Precautions at Work ÂSo Far As Is PracticableÊ: To What Extent This Limitation Exonerates The Employer From Strict Liability Offences Under The OSH Legislation? Master Builders 3rd Quarter 2005. Rozanah, A.R., (2009). Development of Occupational Safety and Health Legislation in Malaysia: With Special Reference to the Factories and Machinery (Amendment) Act 2006. The Law Review 2009, 70–82.