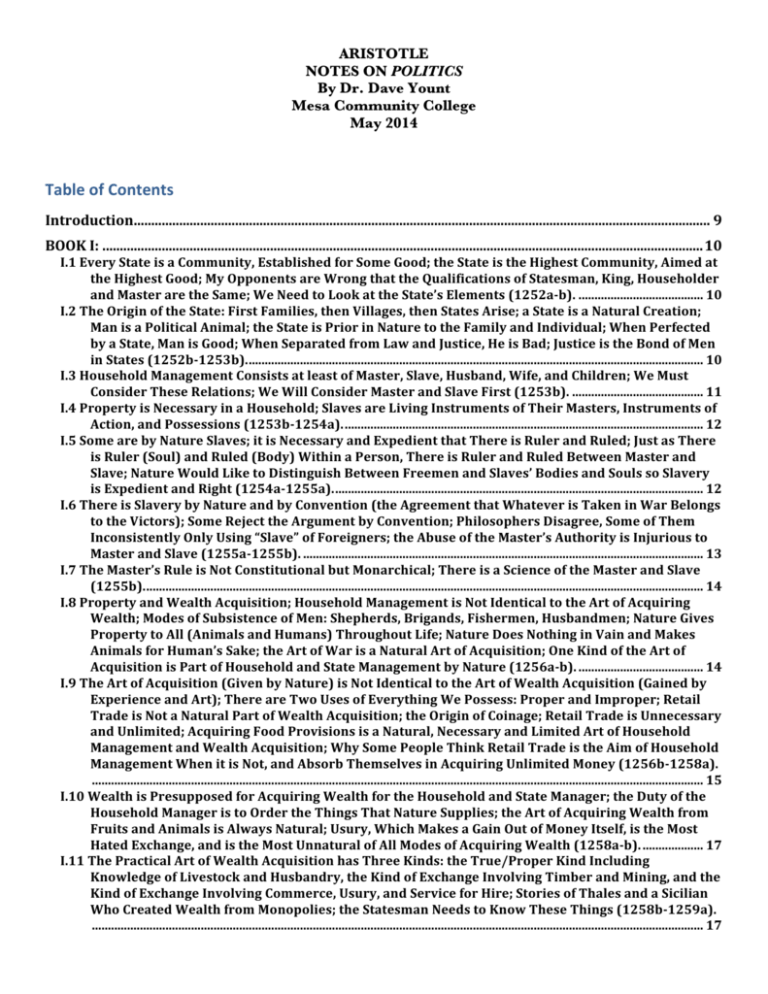

Aristotle's Politics - Mesa Community College

advertisement