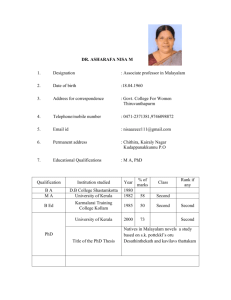

Malayalam: a Grammatical Sketch and a Text

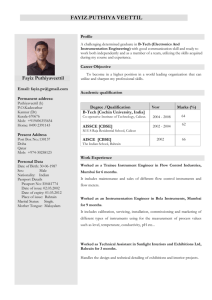

advertisement