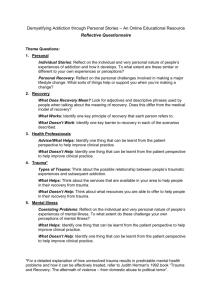

Playing to Heal - Edgework Consulting

advertisement