Sociological Perspectives on Global Climate Change

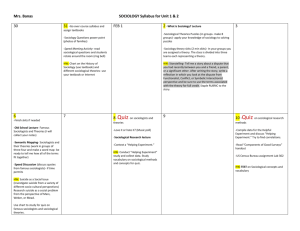

advertisement