Communication and the Capability Problem in Roman Law: Aulus

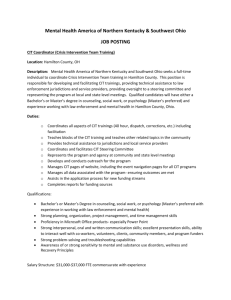

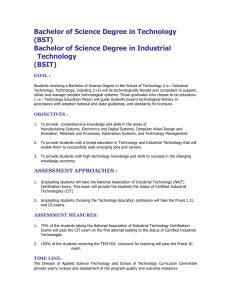

advertisement