The Multiple Faces of Internships

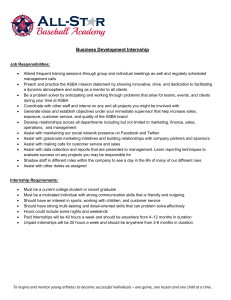

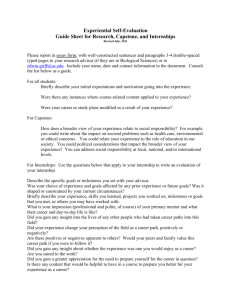

advertisement