An Analysis of James Finn Garner's Politically Correct Bedtime Stor

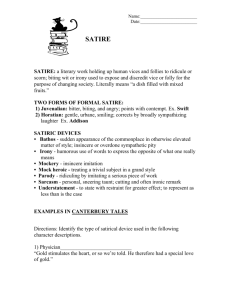

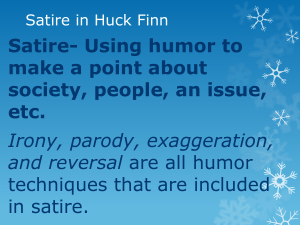

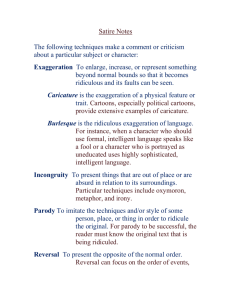

advertisement