Issues and Insights Into the Applicability of the No Child Left Behind

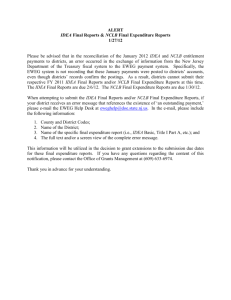

advertisement