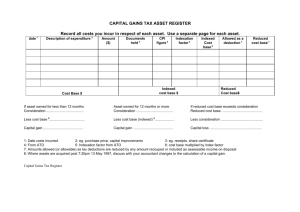

III. Accounting Theory and Alternative Methods for Asset Valuation

advertisement