Lecture 7

advertisement

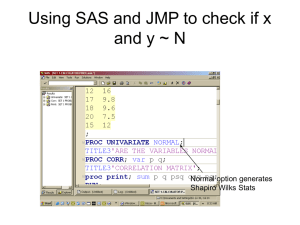

' $ Chapter 7 Analyzing categorical data & % 1 ' $ What is a categorical variable? Examples: • Gender (“Male”,“Female”) • Sick or well • Success or failure • Age group (“Below 20”, “20 to below 40”, “40 to below 60”, “60 and above”) & % 2 ' $ Common techniques used to analyze categorical data • Frequency tables • Contingency tables • Charts • Test of proportion • Chi-square test & % 3 ' $ Questionnaire design and analysis • It is the most common way to collect certain types of data • The data collected can be manually entered into the computer if they are not collected via computer or online. & % 4 ' $ SAS: proc freq data ex7 1; input @1 id $3. @4 age 2.0 @6 gender $1.@7 race $1. @8 marital $1. @9 education $1. @10 subsi 1.0; * Adding labels to the variables; label marital =“Marital Status” education=“Education Level” Subsi=“Baby Subsidy”; datalines; 0012911113 0024522222 0033513244 0042711112 0056821323 0066512432 ; & 5 % ' $ SAS: proc freq proc freq data=ex7 1; title “Frequency Counts for Categorical Variables”; tables gender race marital education subsi; /∗ Alternatively, we can use the following command; tables gender-subsi;∗/ run; & % 6 ' $ SAS output: proc freq & % 7 ' $ SAS output: proc freq & % 8 ' $ SAS: Adding “Value Labels” (Format) proc format; value $sexfmt “1”=“Male” “2”=“Female” Others=“Miscoded”; value $race “1”=“Chinese” “2”=“Malay” “3”=“Indian” “4”=“Others”; value $mari “1”=“Single” “2”=“Married” “3”=“Widowed” “4”=“Divorced”; & % 9 ' $ SAS: Adding “Value Labels” (Format) value $educ “1”=“O-level or Less” “2”=“A-Level or Poly” “3”=“Bachelor degree” “4”=“Postgraduate degree”; value agree 1=“Strongly Disagree” 2=“Disagree” 3=“No Opinion” 4=“Agree” 5=“Strongly Agree”; & % 10 ' $ SAS: Adding “Value Labels” (Format) data ex7 1label; input @1 id $3. @4 age 2.0 @6 gender $1.@7 race $1. @8 marital $1. @9 education $1.@10 subsi 1.0; label marital =“Marital Status” education=“Education Level” Subsi=“Baby Subsidy”; format gender $sexfmt. race $race. marital$mari. education $educ. subsi agree.; & % 11 ' $ SAS: Adding “Value Labels” (Format) datalines; 0012911113 0024522222 0033513244 0042711112 0056821323 0066512432 ; proc freq data=ex7 1label; title “Frequency Counts for Categorical Variables”; tables gender race marital education subsi; run; & % 12 ' $ SAS output: proc freq & % 13 ' $ SAS output: proc freq & % 14 ' $ SAS: Using a format to recode a variable proc format; value agegp low-20=“0-20” 21-40=“21-40” 41-60=“41-60” 60-high=“Greater than 60” .=“Did not Answer” other=“Out of Range”; proc freq data=ex7 1label; title “Using a Fromat to Group a Numeric Varible”; tables age; format age agegp.; run; & % 15 ' $ SAS output: Using a format to recode a variable & % 16 ' $ R: Adding value labels >ex7.1=read.fwf(“D:/ST2137/ex7 1.txt”,header=F, width=c(3,2,1,1,1,1,1)) >names(ex7.1)=c(“id”,“age”,“gender”,“race”,“marital”, “education”,“subsi”) >attach(ex7.1) >gendername=c(“Male”,“Female”) >gendergp=gendername[gender] >gender [1]1 2 1 1 2 1 >gendergp [1] “Male” “Female” “Male” “Male” “Female” “Male” & % 17 ' $ R: Recode a variable >agegpname=c(“low-20”,“21-40”,“41-60”,“61-80”,‘over 80”) >agegp=agegpname[ceiling(age/20)] >age [1] 29 45 35 27 68 65 >agegp [1] “21-40” “41-60” “61-80” “61-80” & % 18 ' $ R: Table >gendername=c(“Male”,“Female”) >gendergp=gendername[gender] >table(gendergp) gendergp Female Male 2 4 & % 19 ' $ R: Table >agegpname=c(“low-20”,“21-40”,“41-60”,“61-80”,“over 80”) >agegp=agegpname[ceiling(age/20)] >table(agegp) agegp 21-40 41-60 61-80 3 1 2 & % 20 ' $ R: Table >racegpname=c(“Chinese”,“Malay”,“Indian”,“Others”) >racegp=racegpname[race] >table(racegp) racegp Chinese Indian Malay 3 1 2 & % 21 ' $ R: Table >marigpname=c(“Single”,“Married”,“Widowed”,“Divorced”) >marigp=marigpname[marital] >table(marigp) marigp Divorced Married Single Widowed 1 2 2 1 & % 22 ' $ R: Table >educgpname=c(“(1)High Sch or Less”,“(2)A-Level or Poly”, +“(3)Bachelor degree”,“(4)Postgraduate degree”) >educgp=educgpname[education] >table(educgp) educgp (1)High Sch or Less (2)A-Level or Poly (3)Bachelor degree (4)Postgraduate degree 2 2 1 1 & % 23 ' $ R: Table >likegpname=c(“(1)Strongly Disagree”,“(2)Disagree”, +“(3)No Opinion”,“(4)Agree”,“(5)Strongly Agree”) >subsigp=likegpname[subsi] >table(subsigp) subsigp (2)Disagree (3)No Opinion (4)Agree 3 2 1 & % 24 ' $ SPSS: Frequency tables • Suppose the data set on slide 5 has been imported into the SPSS. • “Analyze”→ “Descriptive Statistics” →“Frequency...” • Move the variables to the “Variables” panel → “OK” & % 25 ' $ SPSS output: Frequency tables & % 26 ' $ SPSS output: Frequency tables & % 27 ' $ Two-way frequency tables Count the occurrences of one variable at each level of another variable. For example: We would like to know 1. How many males and females were there in the sample? 2. How many respondents were for Candidate A and how many were for Candidate B? 3. How many males and females were for Candidate A and B, respectively? & % 28 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SAS proc format; value $genfmt “M”=“Male” “F”=”Female” Other=“Miscoded”; value $candfmt “A”=“Candidate A” “B”=”Candidate B”; & % 29 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SAS data ex7 2; infile“D:\ST2137\ex7 2.txt”; input gender $ candid $; label gender=“Gender” candid=“Candidate”; format gender $genfmt. candid $candfmt.; run; proc freq data=ex7 2; tables gender*candid/chisq; run; & % 30 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SAS output & % 31 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SAS output & % 32 ' $ Computing Chi-square from frequency counts: SAS /*Computing Chi-square from frequency counts*/ data ex7 2c; input group $ outcome $ count; datalines; drug alive 90 drug dead 10 placebo alive 80 placebo dead 20 ; proc freq data=ex7 2c; tables group*outcome/chisq; weight count; run; & % 33 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SAS output & % 34 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SAS output & % 35 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: R >ex7.2=read.table(“D:/ST2137/ex7 2.txt”,header=F) >names(ex7.2)=c(“gender”,“candid”) >table(ex7.2) candid gender A B F 70 30 M 40 40 & % 36 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: R >chisq.test(table(ex7.2)) Pearson’s Chi-squared test Yate’s continuity correction data:table(ex7.2) X-squared=6.6626,df=1,p-value=0.009846 Computing chi-square from the frequency counts: R >v=matrix(c(90,10,80,20),nc=2) >v=data.frame(v) >names(v)=c(“Alive”,“Dead”) >row.names(v)=c(“Drug”,“Control”) >chisq.test(v) Pearson’s Chi-squared test with Yate’s continuity correction data:v X-squared=3.1765, df=1, p-value=0.0747 & % 37 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SPSS • “Analyze”→ “Descriptive Statistics” →“Cross Tables...” • Move one of the the variables to the “Row” window and second variable to “Column(s)” window. & % 38 ' $ Two-way frequency tables: SPSS • Click on “Statistics” • Choose “Chi-square” or some other statistics → “Continue”→“OK” & % 39 ' $ Computing Chi-square from frequency tables: SPSS • Data file as shown below • “Data”→‘Weight Cases” • Move the variable “Count” to the “Frequency Variable” panel under “Weight cases by option” • Proceed as on p38-39. & % 40 ' $ Computing Chi-square from frequency tables: SPSS & % 41 ' $ Paired Data • Paired data arise when the subjects are responding to a question under two different conditions (e.g. before and after treatment). • Paired designs are also used when a specific person is matched on some criteria, such as age and gender, to another person for the purpose of analysis. & % 42 ' $ McNemar’s test for paired data: SAS proc format; value $opin “p”=“Positive” “n”=“Negative”; run; data ex7 3; length before after $1.; infile “D:\ST2137\ex7 3.txt”; input subject before $ after $; format before after $opin.; proc freq data=ex7 3; title “McNemar’s Test for Paired Samples”; tables before *after/agree; run; & % 43 ' $ McNemar’s test for paired data: SAS output & % 44 ' $ McNemar’s test for paired data: SAS output & % 45 ' $ McNemar’s test for frequency counts: SAS proc format; value $opin “p”=“Positive” “n”=“Negative”; run; data ex7 3c; length before after $1.; input after $ before $ count; format before after $opin.; datalines; n n 32 n p 30 p n 15 p p 23 ; & % 46 ' $ McNemar’s test for frequency counts: SAS proc freq data=ex7 3; title “McNemar’s Test for Paired Samples”; tables before *after/agree; weight count; run; & % 47 ' $ McNemar’s test: R #Example 7.3 >ex7.3=read.table(“D:/ST2137/ex7 3.txt”,header=F) >names(ex7.3)=c(“ID”,“Before”,“After”) >attach(ex7.3) >mcnemar.test(table(ex7.3[,2:3])) McNemar’s Chi-square test with continuity correction data:table(ex7.3[,2:3]) McNemar’s chi-squared=4.3556,df=1,p-value=0.03689 & % 48 ' $ McNemar’s test for Frequency Counts: R #Example 7.3c: Handling frequency counts >ex7.3c=matrix(c(32,15,30,23),nr=2,byrow=T, +dimnames=list(“Before”=c(“No”,“Yes”),“After”=c(“No”,“Yes”))) >ex7.3c After Before No Yes No 32 15 Yes 30 23 >mcnemar.test(ex7.3c) McNemar’s Chi-squared test with continuity correction data:ex7.3c McNemar’s Chi-squared=4.3556,df=1,p-value=0.03689 & % 49 ' $ McNemar’s Test: SPSS • “Analyze”→ “Descriptive Statistics” →“Crosstabs...” • Move “Before” to the “Row” window and “After” to “Column(s)” window. • Click on “Statistics...” and choose “McNemar” • “Continue”→“OK” & % 50 ' $ McNemar’s Test: SPSS & % 51 ' $ McNemar’s Test: SPSS If frequency counts are available instead of the raw data, then we can weight the data in the following way. “Data”→“Weight Cases..” & % 52