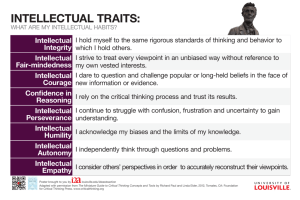

Intellectual capital and the 'capable firm'

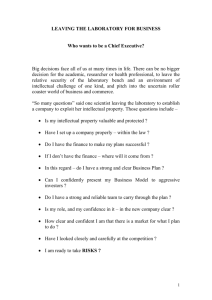

advertisement