Advertising into the next millennium

advertisement

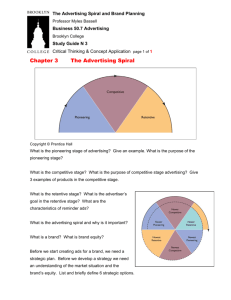

Published by NTC Publications Ltd Farm Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EJ, UK Tel: +44 (0)1491 411000 Fax: +44 (0)1491 571188 Vol 17 No 4 (1998) Advertising into the next millennium Ashok Ranchhod This is a conceptual paper based on the evolution of marketing and advertising in a world that is increasingly dominated by technology. Markets, according to postmodern thought, are beginning to fragment, yet at the same time they are creating greater challenges for advertisers. Individuals are both isolated and at the same time interconnected with virtually the whole world via computers. Advertising has for a long time been based on a one-to-many communications model, yet new technology offers the possibility of a computer-mediated environment, in effect, a virtual world. This paper tries to make sense of the Internet and contemporary thought for developing advertising effectiveness. It concludes with eight propositions for further empirical research into the area of advertising effectiveness in a computer-mediated environment, in a postmodern world. INTRODUCTION Marketing has evolved over the last two centuries, as the systems of production and consumption have changed owing to the rapid development of technology. The rate of development in technology has seen the advent of mass manufacturing, instant communication systems and the development of rapid transport systems. It is clear that marketing initially moved from fragmentation to mass marketing to segmentation marketing (Tedlow, 1993). There is now another technological drive, owing to powerful computing techniques (Patron, 1996). The increasing globalisation of communication for the average person (Cronin, 1996) and the development of technologies for flexible manufacturing (Yasumuro, 1993) is leading marketers to consider the absolute dislocation of time and space in undertaking marketing transactions. The Internet, in turn, offers a virtual 24hour shopping experience in any market sector, for any person in the world who is able to access it. Figure 1 shows the development of these phases and also alludes to the possibility that markets may yet again be fragmenting (Ranchhod and Hackney, 1997), due to the ease of communication. This is paradoxically in contrast to the early part of the nineteenth century when markets were fragmented as a result of poor communications and transport systems. Certainly much of the literature on postmodernism seems to point towards fragmentation. According to Cova (1996), the fragmentation of society, made possible and fostered by the developments of industry and commerce, is among the most visible consequences of postmodern individualism. This fragmentation, he argues, is encouraged by the ability of the individual to maintain 'virtual' contact with the world, electronically, freeing the individual from social interaction but at the same time increasing the concentration of the ego, placing demands for 'tailored' products and services in the marketplace. There are indications that some of the demographic and lifestyle changes in society are just beginning to offer such a scenario. THE ROLE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Computing power has expanded enormously in the last decade with the processing power available doubling every 18 months. This capacity has given marketers a chance to grapple with extraordinary detail, every consumer's preferences, the development of products and an integrated marketing strategy. Companies with processing power equivalent to the large mainframe IBM computers, which existed ten years ago, are now within easy reach of most individuals. The development in the foreseeable future of a sophisticated database is therefore possible for many small companies. Much statistical data can be gathered, leading to both market research facilities and to an external market intelligence overlay on to general trends within an organisation. Not only is this possible, but the detailed access allows site evaluation and sales forecasting. The system can be used to drive shelf-planning, inventory control and the development of communication strategies. Data collection points can potentially give advertisers a chance to gauge the effectiveness of certain campaigns, and can also help organisations to develop integrated marketing communications linking various disparate sets of data. Some companies are now using technology to further improve their marketing communications efforts which were previously impossible or very difficult, given the computing software and level of computing power available. The Internet is now becoming another possible source of advertising and of data collection. ADVERTISING & ADVERTISING EFFECTIVENESS Much of the research into advertising effectiveness has been well documented by the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising in the United Kingdom. The detailed impact of advertising campaigns on sales and potential profits for companies is also available. All the studies highlight the importance of branding and the subsequent strategies to enhance the 'value' of the brand to the customer. According to Ambler (1995): 'A brand is the promise of a bundle of attributes that someone buys and provides satisfaction. The attributes may be tangible or invisible, rational or emotional.' The most important element is the fact that people 'buy' the brands and also 'buy into' the brands in order to receive some 'satisfaction' (Broadbent, 1997). According to Broadbent a brand is something 'unique' and offers a substantial difference to the competitive products on offer in the marketplace. This distinctiveness is often emphasised through targeted television campaigns. For instance, Leather et al. (1994) discuss the importance of television advertising effectiveness. Central to their argument is the role played by likeability in advertising. This factor is important in predicting advertising effectiveness (Biel and Bridgewater, 1990; Haley, 1990) as a diagnostic tool (Aaker and Stayman, 1990) and as a gatekeeper for further information processing. They argue that people watching commercials need to like them in order to be persuaded. Their study details likeability and links it to several factors within particular advertisements, such as: stimulation, relevance, situational dynamism, positive impact, originality, sex appeal, stereotypicality, ambience, quality and realism. This range of factors is quite wide but is nevertheless an important backdrop for research. Other authors such as Neal and Bathe (1997) have considered working through the value equation by Russell and Kamakura (1991) and Park et al. (1994). The total value of a brand in a particular product/service category is composed of three key parts. The first part surrounds the tangible product features impacting on purchase choice. The tangible features are physical and identifiable. The second set of features are those related to the image transferred to the purchaser. The perceived image and value to the purchaser may be such factors as trust, longevity in the market, consistency of performance and the creation of a desired emotional state. These factors form the brand's image. The third part of the equation lies in the price of the product, which to a large extent is dependent on the factors discussed above. Batra et al. (1995), using tracking data for their research, consider when advertising has an impact. It appears from their work that although advertising has only a limited short-term sales impact, it may have a bigger effect on many of the brand equity variables discussed above. Batra and Ray (1986) found that repeated exposure to certain brands meant less need for advertising as messages were absorbed quickly. Other studies showed that familiarity or loyalty to a brand meant repetition could be profitably employed (Aaker and Carman, 1982). Repetition also seemed to work with complex ad messages (Anand and Sternthal, 1990), or when there is more competitive spending (Burke and Srull, 1988) or advertising clutter (Webb and Ray, 1979). The re- inforcement effect seems to be important for loyal customers. Overall, Batra et al. (1995) found a strong and significant increase in the effect of advertising when the product category was new or growing. On the other hand, Hollis (1995) attempts to show that a new measure of consumer involvement with advertising is also important in predicting whether or not advertising messages and associations will pass into people's memory. Figure 2 shows the grid for involvement factors for 30 UK advertisements. Hollis placed advertisements in the boxes shown in Figure 2 on the following bases, using three sets of four participants, each set being divided into positive and negative, active and passive. l Active/positive, for example interesting. l Passive/positive, for example soothing. l Active/negative, for example irritating. l Passive/negative, for example ordinary. Hollis concludes that the role of involvement and memory will, in future, prove to be even more important in achieving a longer-term effect than is true of predicting short-term sales effects. This section has tried to establish some of the key current issues in advertising effectiveness and some of the directions in which empirical research is going. The pointers towards frequency, liking and involvement are useful for trying to understand the role that the Internet could possibly play in advertising. THE ROLE OF THE INTERNET The last three to four years have seen an explosive growth in the number of people using the Internet. Interconnectivity with simple and powerful computers theoretically offers the opportunity to link with anyone on a global basis with the use of a modem. The open software written by companies such as Netscape enables access to information concerning companies, individuals, marketing data, brochures, pictures, science, specific discussion groups, music, sports, politics and a host of other sources. The current worldwide usage is estimated to be around 60 million (with e-mail addresses), though in a rapidly growing medium figures can be somewhat suspect. However, Dr Vinton Cerf, one of the developers of the Internet's data transfer protocols, testified to the US House of Representatives that: 'There is reason to expect that the user population will exceed 100 million by 1998' (Ellsworth and Ellsworth, 1996). Perhaps what is more important is to consider the way network servers are growing in the top 25 countries, reflecting the appetite of businesses and consumers alike in connecting to the World Wide Web. Table 1 summarises the statistics to date. Of course the speed of growth is overwhelming and the latest statistics could show a different rate of growth in the different countries. This simultaneous expansion of communication for both the consumers and businesses alike is perhaps heralding the growth of 'business without borders'. Owing to the fact that the Internet removes many barriers to communication, obstacles such as time zones, geography and location do not matter, and so a 'frictionless' business environment is theoretically possible (Anderson, 1997). The main growth is expected to be in the 'business-to-business' area. Anderson argues that 'ubiquitous and equal access to information will create the closest thing yet to Adam Smith's perfect market'. Are the rules, therefore, that governed advertising strategies to date, drastically changing? TABLE 1: NETWORK GROWTH BY COUNTRY 1994-1995 Country United States Canada France Australia Japan Germany United Kingdom Finland Taiwan Italy Korea, South Czech Republic South Africa Sweden Austria Netherlands Russian Federation New Zealand Switzerland Spain Israel Norway 1994 11,278 757 745 400 579 743 699 210 174 262 88 104 111 148 125 202 216 114 150 90 106 129 1995 28,470 4,975 2,003 1,875 1,847 1,750 1,436 643 575 506 476 459 419 415 408 406 405 356 324 257 217 214 % Growth 152 533 169 369 219 136 105 206 231 93 441 341 278 180 226 101 88 212 116 186 105 60 Norway Ireland Brazil Hungary 129 52 111 72 214 168 165 164 60 223 49 128 Source: NIC MERIT /nsfnet/statistics/nets.by.country. Essentially, firms communicate with their customers through various forms of media. Most media allow the customers a passive approach to communication and limited forms of feedback. The previous discussions alluded to the fact that much of the feedback data is gathered through extensive market research or laboratory testing to understand the effectiveness of advertising. The Internet offers a computer-mediated environment (CME) on a global basis. The World Wide Web, most importantly from a marketing viewpoint, provides an efficient channel for advertising, marketing and even direct distribution of certain goods and services (Hoffman and Novak, 1996). Certain authors argue that the Web can save companies up to nine-tenths of their advertising budget (Potter, 1994; Verity and Hof, 1994). According to Kassaye (1997) who undertook a Porter (1985) analysis of the effect of the World Wide Web on agency-advertiser relationships, many companies are likely to use computer design studios and boutiques or resort to producing in-house advertisements. What does this brave new world of marketing communications have to offer marketers? First of all it offers a distinct change from the traditional one-to-many marketing communications model that is currently effective for mass media (Figure 3). There is no interaction between consumers and firms in this environment. The communications model outlined by Steuer (1992) and Hoffman and Novak (1996a), explains that in the mediated model, the primary relationship is not between the sender and the receiver, but rather with the mediated environment with which each party interacts. The important factor here is the chance the users get to participate in feeling and modifying the form and content of the environment. The depth of the experience is largely what a person feels in the hypermedia CME. Figure 4 shows the range of communication possibilities, with consumers being able to put product-related content in the medium, ranging from gardening issues (for instance, garden web sites) to toys (for instance, Lego, Barbie Dolls and Teletubbies) to television shows (Friends and The X-Files). Internet presence gives firms a non-intrusive form of advertising (at present), largely because many computer users do not have access to sound or video clips usage. The whole premise of advertising on the Internet relies on involvement, the way in which customers 'flow' through the medium and the use of structured activities, offering individuals a completely different form of experience compared to standard television advertising. Potentially there is also the chance for instant fulfilment through being able to place an order for a particular good or service. Earlier, this paper expressed the role of involvement in advertising in achieving a longer-term effect for a particular brand (Hollis, 1995). The Internet offers just such a possibility, with Net surfers being able to delve deeper into the Web pages for further information and to select favourite sites as 'bookmarks'. THE INTERNET, POSTMODERN MARKETING & GLOBALISATION Much of the discussion on postmodern marketing emphasises the growing importance of digital/communicative technologies, communication, consumption, images/symbols and hyper-reality (Venkatesh et al., 1993). According to Cova (1996), postmodernism champions individuality and the modern quest for liberation from social bonds. The fragmentation of society shows the consequence of postmodern individualism. He argues that: 'Paradoxically, the postmodern individual is both isolated and in virtual contact with the whole world electronically. Postmodern daily life is characterised by ego concentration, encouraged by the spread of computers.' Figure 5, adapted from Cova's article, shows the juxtaposition of opposites in the postmodern world. Cova goes on to say that in postmodern marketing one has to offer the following. l One-to-one marketing with the use of IT. Unpredictable and individualistic customers could be retained this way. l Image Hyper-reality is the potential to offer experience similar to Euro-Disney's theme parks. Technology offers the postmodern consumer the chance to be a participant in customising his or her own world. l Marketing images The era of postmodern marketing relies on image marketing (Venkatesh et al., 1993), emphasising cultural meanings and images. Cova (1996) feels that image marketing and brand management are closely related. Rather controversially he argues that we are witnessing the obsolescence of advertising: `In postmodern markets, advertising simply misses the fundamental point: to be an interactive experience of co-creation of meaning for the customer. ' l Fragmentation Meuller-Heumann (1992) outlines in his important paper why market and technology shifts in the 1990s are pointing towards market fragmentation and mass communication. The fragmentation of markets is likely to herald a greater emphasis on smaller and more unstable segments. In many respects it could be argued that this type of postmodern world is not quite a reality for many people. Authors such as Clegg (1991) would argue that we are seeing signs of modernity, with seamless societal changes taking place in different cultural contexts rather than complete paradigm changes. It would be facile to tackle this contentious issue in this paper. Nonetheless, some of the arguments put forward have relevance in this new world of almost instant global communications. Ironically, much of the postmodern emphasis on fragmentation and individualism seems to be borne out by the experience of companies on the Internet. For instance, companies such as Tripod and Geocities (Hof et al., 1997) have made a virtue out of helping to build 'community-type' discussion areas, which allow communication over large geographic areas. Tripod offers editorial content and discussions are grouped into fields such as politics, health and money. The target audience are the 'twenty-somethings'. Individuals are encouraged to design and build their own Web pages. In these locations, larger companies such as Ford, Visa, Sony and Microsoft take banner advertising space. The demographics of the community play a large part in segmenting the advertising spend for the larger companies as the target group are mainly aged 18-34, living in the US and 75 per cent male. Another interesting example of this community-based discussion area is provided by Geocities, which has formed a 'virtual' city allowing communities to develop and flourish, eventually exchanging or selling homes and also settling into new neighbourhoods. Armstrong and Hagel (1996) discuss the merits of on-line communities and explain how the Garden Web area has evolved into a very successful community, where ideas are shared, plants are exchanged and links with related businesses and resources are forged. In this sense, it is a powerful area for an advertiser to be in, rather than in a simple site that allows only transactions. THE INTERACTION OF ADVERTISING, THE INTERNET GLOBALISATION The discussion above shows the complexities that are beginning to develop in marketing and advertising. It appears that there is a move towards individualism and fragmentation. Cybermarketing is allowing both smaller and larger companies an effective marketing medium for communication on a global basis. For multinationals, the model appears to move from information to transaction (Figure 6). 3M's Web site gives information on its products and news about innovations and, at the same time, the company is making forays into selling simple products. Internet start-ups or smaller companies, on the other hand, work towards a transaction/information model in order to minimise cost, as shown in Figure 7. They can then continue to spend more time building brand image, providing product support and winning repeat purchases where possible. A small business success story in this area is a company such as Jack Scaife butchers in Keighley in Yorkshire (Oldfield and Burnham, 1997). The Internet offers ample opportunities for new product diffusion, the possibility of adapting products and services to meet local requirements and niche product selling by smaller companies to an instant global audience. Jack Scaife butchers sell cured pork over the Internet and receive a substantial number of e-mails from Hong Kong and Japan. Currently, the population on the Net is quite diverse with 45 per cent of the adults surfing the Net aged 40 or over, and 32 per cent between 18 and 29. In fact women make up 41 per cent of the Net population. In general, the adult Net users are more affluent and better educated than the population as a whole. More than 42 per cent have household incomes greater than £35,000 compared with 33 per cent of the overall population, and 73 per cent of Net surfers have attended college versus 46 per cent of the total population (Hof et al., 1997). Given the general scenarios of globalisation, market fragmentation and the increasing use of CME, further research should more explicitly profile the relationship between advertising effectiveness and the use of the Internet. Such research could be planned around the following propositions. P1. Individuals are likely to cluster their preferences for brands along 'community-based' activities on the Internet. The discussions above allude to the fact that community or 'tribal' groups are beginning to emerge on the Net. For advertisers, it is important to be able to understand these groupings as potential segments for certain brands or groups of brands. The research design to test this proposition would collate data from specific community groups and monitor any brand preferences within that group. P2. The fragmentation of markets will mean the fragmentation of the advertising of brands into several different segments on a global basis. The above proposition is more contentious given the current views that brands are powerful entities, having a major pull on consumers in cosmopolitan cities (Willman, 1997). The main argument, however, is whether the brands are evolving along the lines of groups mentioned in P1. Some analysis along these lines would provide serious insights into the current vogue for integrated marketing strategies. Would parallel branding strategies be important? P3. Small companies will be able to advertise more effectively than before, potentially eroding the market share of larger companies. This proposition is based on the cheapness and ease of using the Web. It is entirely possible that small companies will grow at the expense of the larger concerns as they are likely to be more flexible and can advertise cheaply on the Web. In fact, Kassaye (1997) argues that the new medium challenges the advertiseragency relationships and allows a new breed of computer programmers in management information systems departments a chance to develop excellent Web sites. This overturns the norm of advertising where having a big brand and hence more money to spend helps to create effective advertising. Big brands will obviously continue to have an impact, but the segments will become much more competitive and fragmented. Clark (1997) argues that as just one Web 'store' reaches the world, markets that are too small on a local basis can become viable on a global one. The big brands, nonetheless, will have the financial muscle to offer varied Web sites and a great deal of passive advertising. It would be useful to explore how the balance of power is changing. P4. Increasingly, advertising effectiveness will rely on likeability enhanced by greater involvement. This degree of involvement will be provided through Internet access. This goes back to the earlier discussion on the need for participants to like the advertisements (Leather et al., 1994), as well as the need to be involved (Hollis, 1995). Hollis argues that liking is not enough and that the role of involvement and memory is important. If, however, through access such as e-mail, people are 'leaving a piece' of themselves in the virtual world, then direct involvement with the brands in the form of communication and discussion with peer groups will add to the development of like (or dislike) for a brand as well as embedding into memory. Hoffman and Novak (1996b) discuss the concept of 'flow' and the idea that individuals 'lose' track of time on Web sites, becoming more involved in the interactive environment than in the physical surroundings. When in 'flow', individuals learn, explore, participate and, above all, spend more time at sites which offer a positive experience. P5. Multi-media and animation will play a greater part in developing effective advertising. The new technology now allows for animation and 'dancing' logos to be displayed. Explorers may well be attracted and involved with such sites, adding to the effectiveness of advertising. Brands would need to offer 'memorable' experiences encompassing sight, sound and 'fun', with the possibility of simple games to enhance the memory process. P6. Advertising on the Internet will allow for more effective data collection on cause/effect relationships. This proposition is put forward, namely because registration or subscription to a site allows demographic and other information, as well as e-mail addresses, to be collected, allowing for better analysis of data and better targeting. This could become a virtual circle for advertising effectiveness (Paul, 1996). This proposition needs to be tempered by the fact that many people may see this as an invasion of their privacy. Nevertheless, on the Web it is currently possible to search for e-mail addresses on a worldwide basis. Through further research into P4 to P6, some interesting results could be obtained, extending and enhancing many of the relationships between advertising style and the effect of a CME. Further hypotheses could then be developed as extensions of P4 to P6 as suggested below. P7. Advertising effectiveness will be enhanced by individual learning and liking for a brand through use and effective interaction within a CME. In this proposition, studies surrounding the fluency of use of a CME by the participants, including good Web designs (from the point of ease of use, interest and likeability) would help to create a better understanding of advertising effectiveness. The ways in which Internet advertising complements conventional advertising could also be ascertained. P8. Advertising effectiveness within a CME will be dependent on optimum use of state-of-the-art technology on the part of the consumer. This proposition would attempt to uncover the current problem of the type of accessibility to a CME. Most people replace their computers infrequently and therefore the computer environment experienced by one household may be substantially different from another household. The speed and state of the technology is therefore likely to impact on how companies can create effective advertising and also on how it is received and perceived at the other end. CONCLUSION & IMPLICATIONS Individuals learn and respond to various stimuli. What they know and understand affects how they interpret messages and advertisements. Considerable strides have been made in assessing the impact of television advertising and some studies are often tightly controlled in laboratory-based situations. If we accept the point that an individual processes information according to his or her shared understanding, which constitutes memory, then it is important to try to ascertain the impact of community-based or individual interaction on advertising effectiveness. Previously, most mediums did not allow the development of such interaction, whereas a CME does. The way these processes occur and the way individuals interplay within this environment would provide us with a wealth of information which could fundamentally alter our perceptions of the current one-to-many advertising model. Advertisers take time to learn about their markets and try to alter their markets by advertising and creating and sustaining brands. It would be interesting to gauge, in a more 'hands-on' manner, whether the range of potential behaviour of consumers has changed, or indeed is changing in a particular direction. This would allow marketers to pre-empt certain changes already in motion within the marketplace. The time has come for a new look at the concept of advertising effectiveness, encompassing a different unexplored paradigm. The markets appear to be fragmenting as we move into the so-called postmodern world. How do we deal with advertising where image could be everything and hyper-reality could rule? ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank the anonymous referees for helping to improve this paper and Tim Ambler for his useful comments and pointers. REFERENCES Aaaker, D.A. & Carman, M. (1982) 'Are you over-advertising?', Journal of Advertising Research, 27(3), 345353. Aaker, D.A. & Stayman, D.M. (1990) 'Measuring audience perceptions of commercials and relating them to ad impact', Journal of Advertising Research, 30(4), 7-17. Ambler, T. (1995) Marketing from Advertising to Zen, A Financial Times Guide. London: Pitman. Anand, P. & Sternthal, B. (1990) 'Ease of message processing as a moderator of repetition effects in advertising', Journal of Marketing Research, 27(3), 345-353. Anderson, C. (1997) 'Electronic commerce', The Economist, Special Section, 343(8016), 5 March. Armstrong, A. & Hagel, J. III (1996) 'The real value of on-line communities', Harvard Business Review, 74(3), 134-141. Batra, R. & Ray, M. (1986) Situational effects of advertising repetition, Journal of Consumer Research, 12(4), 432-445. Batra, R., Lehmann, D.R., Burke, J. & Pae, J. (1995) 'When does advertising have an impact? A study of tracking data', Journal of Advertising Research, 35(5), 14-19. Biel, A.L. & Bridgewater, C.A. (1990) 'Attributes of likeable television commercials', Journal of Advertising Research, 30(3), 38-44. Broadbent, S. (1997) Accountable Advertising. Henley-on-Thames: Admap Publications. Burke, R.R. & Srull, K. (1988) 'Competitive interference and consumer memory for advertising', Journal of Consumer Research, 15(1), 55-68. Clark, B.R., (1997) 'Welcome to my parlor', Marketing Management, 5(4), Winter, 11-25. Clegg, S.R. (1991) Modern Organizations, Organization Studies in the Postmodern World. London: Sage Publications. Cova, B. (1996) 'What postmodernism means to marketing managers', European Management Journal, 14(5), 494-499. Cronin, M.J. (1996) Global Advantage on the Internet. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Ellsworth, J.H. & Ellsworth, M.V. (1996) New Internet Business Book. London: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Haley, R.I. (1990) 'The ARF copy research validity report: a top-line report', in Proceedings of the Advertising Research Foundation 36th annual conference, New York. Hof, D.R., Browder, S. & Elstrom, P. (1997) 'Internet communities', Business Week, 5 May, 38-45. Hoffman, D.L. & Novak, P.T. (1996a) 'Marketing in computer-mediated environments: conceptual foundations', Journal of Marketing, 60(3), 50-68. Hoffman, D.L. & Novak, P.T. (1996b) 'You can't sell if you don't have a market you can count on. The future of interactive marketing', Harvard Business Review, 74(6), November-December, 151-162. Hollis, N.S. (1995) 'Like it or not is not enough', Journal of Advertising Research, 35(5), 7-10. Kassaye, W.W. (1997) 'The effect of the World Wide Web on agency-advertiser relationships', International Journal of Advertising, 16, 85-103. Leather, P., McKechnie, S. & Amirkhanion, M. (1994) 'The importance of likeability as a measure of television advertising effectiveness', International Journal of Advertising, 13, 265-280. Meuller-Heumann, G. (1992) 'Market and technology shifts in the 1990s: market fragmentation and mass customization', Journal of Marketing Management, 8, 303-314. Neal, W.D. & Bathe, S. (1997) 'Using the value equation to evaluate campaign effectiveness', Journal of Advertising Research, 37(3), 80-86. Oldfield, C. & Burnham, N. (1997) 'Internet brings home the bacon', The Sunday Times, Business Section, 2 March, 10. Park, S.C. & Srinivasen, V. (1994) 'A survey-based method for measuring and understanding brand equity and its extendibility', Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2), 271-288. Patron, M. ( 1996) 'The future of marketing databases', Journal of Database Marketing, 4(1), 6-10. Paul, P. (1996) 'Marketing on the Internet', Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(4), 13-27. Porter, M.E. (1980) Competitive Strategy. New York: Free Press. Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free Press. Potter, E. (1994) 'Commercialization of the World Wide Web', Internet conference on the WELL, 16 November. Quelch, J.A. & Klein, L.R. ( 1996) 'The Internet and international marketing', Sloan Management Review, 37 (3), 60-75. Raj, S.P. (1982) 'The effects of advertising on high and low consumer segments', Journal of Consumer Research, 9(1), 77-89. Ranchhod, A. & Hackney, R. (1997) 'Marketing through information technology: from potential to 'virtual' reality', Proceedings of the first annual Academy of Marketing Conference, 1, 781-791. Russell, G. & Kamakura, W. (1991) MSI Report, April, 91-110. Steuer, J. (1992) 'Defining virtual reality: dimensions determining telepresence', Journal of Communication, 42 (4), 73-93. Tedlow, R. (1993) 'The fourth phase of marketing', in The Rise and Fall of Marketing (ed.) Tedlow, R.S. & Jones, G. London: Routledge. Venkatesh, A., Sherry, J.F. & Firat, A.F. (1993) 'Postmodern and the marketing imaginary', International Journal of Research in Marketing, 10(3), 215-223. Verity, J.W. & Hof, R.D. (1994) 'The Internet: how will it change the way you do business', Business Week, 14 November, 80-86. Webb, P. & Ray, M. L. (1979) 'Effects of TV clutter', Journal of Advertising Research, 19(3), 7-12. Willman, J. (1997) 'Shimmering symbols of the modern age', in The Global Comany - Part 6, Financial Times, 12. Yasumuro, K. (1993) 'Conceptualising an adaptable marketing system', in The Rise and Fall of Marketing (Ed) Tedlow, R.S. & Jones, G. London: Routledge. © Advertising Association http://www.warc.com NOTES & EXHIBITS Ashok Ranchhod Ashok Ranchhod is associate professor and head of marketing at Southampton Business School. He has also worked at the Nottingham, Sheffield and Open University Business Schools. Before working in academia, he ran a plant biotechnology company. For many years he has been an external examiner at various business schools throughout the country. He is now the senior examiner at the Chartered Institute of Marketing for the case study paper (analysis and decision). He has run senior manager programmes for several multinational companies and published widely on marketing subjects in various journals. His current interests surround marketing strategies for biotechnology companies and effective market orientation with the use of technology. FIGURE 1: THE IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY ON MARKETING FIGURE 2: INVOLVEMENT FACTOR (30 UK ADS) Source: Hollis, 1995 FIGURE 3: TRANSITIONAL ONE-TO-MANY MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS MODEL FOR MASS-MEDIA Source: adapted from Hoffman and Novak, 1996a FIGURE 4: MEDIATED COMMUNICATION MODEL Source: adapted from Steuer (1992) FIGURE 5: POST-MODERN MARKETING AS A JUXTAPOSITION OF OPPOSITES Source: Cova (1996) FIGURE 6: EVOLUTIONARY PATHS OF A WEB-SITE Source: adapted from Quelch and Klein (1996) FIGURE 7: INTERNET START-UPS Source: adapted from Quelch and Klein (1996)