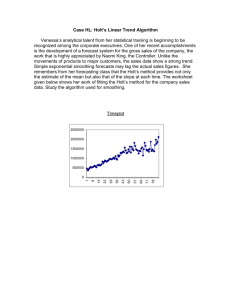

Guidance Note on the Practice of Smoothing the Profits

advertisement