Ecological Modernization and Its Critics: Assessing the Past and

Society and Natural Resources, 14:701–709, 2001

Copyright 2001 Taylor & Francis

0894-1920/2001 $12.00

.00

Insights and Applications

Ecological Modernization and Its Critics:

Assessing the Past and Looking Toward the Future

DANA R. FISHER

Department of Sociology/Rural Sociology

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Madison, Wisconsin, USA

WILLIAM R. FREUDENBURG

Department of Rural Sociology

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Madison, Wisconsin, USA

The theory of ecological modernization has received growing attention over the past decade, but in the process, it has been interpreted in con icting and sometimes contradictory ways. In this article, we attempt to bring greater clarity to the discussion. Reviewing the works both by the theory’s best-known proponents and by its most outspoken critics, we note that dif culties are created not just by the combining of theoretical predictions and policy prescriptions —a point that has already been noted in the literature —but also by the stark and highly signi cant differences in expectations between ecological modernization and most prevailing theories of society –environment relationships. Perhaps in part because of these differences, disagreements have often been expressed in stark, black-and-white terms. If the problems are to be resolved, there will be a need for greater theoretical precision, developed in conjunction with empirical research that is more focused, more nely differentiated, and more rigorous.

Keywords ecological modernization, environment –society relationships, global environmental change, social theory

Roughly 10 years ago, Society and Natural Resources published the rst article on the theory of ecological modernization in the English language (Spaargaren and Mol 1992).

Since then, the arguments of ecological modernization have received growing attention, both within the subdiscipline of environmental sociology and in broader debates over major social theories (see, e.g., Bl¨uhdorn 2000; Buttel 2000a; 2000b; Christoff 1996;

Cohen 2000; Giddens 1998; Hajer 1995; Leroy and van Tatenhove 2000; Mol 1995;

1997; 1999; 2000a; 2000b; Mol and Spaargaren 1993; 2000; Spaargaren 1997; 2000;

Received 1 November 1999; accepted 13 September 2000.

The authors thank the anonymous reviews for Society and Natural Resources.

Address correspondence to Dana R. Fisher, Department of Sociology/Rural Sociology,

University of Wisconsin-Madison, 350 Agriculture Hall, 1450 Linden Drive, Madison, WI

53706. E-mail: d sher@ssc.wisc.edu

701

702 D. R. Fisher and W. R. Freudenburg

Spaargaren and Mol 1992; Spaargaren and van Vliet 2000; Pellow et al. 2000). To date, however, cumulation has been limited by inconsistencies and incompatibilities in the interpretations of the theory that have been put forward. In this article, we brie y summarize both the theory and the major responses to it, subsequently offering our suggestions on the types of research offering the greatest promise for moving the debate in a constructive direction.

The Theory and Its Critics

Ecological modernization was originally presented in the German language by Huber

(1985, 1991). Many of the debates surrounding the theory, however, have been in response to English-language treatments, particularly those by Mol and Spaargaren

(1993; 2000; Spaargaren and Mol 1992; Spaargaren 1997; 2000; Mol 1997; 1999;

2000a; 2000b). Our discussion focuses on the work in the English language, paying special attention to the publications that have focused on clarifying key issues.

Although the theory of ecological modernization presents a complex understanding of postindustrial society (for fuller discussions, see especially Mol 1997; Spaargaren and Mol 1992), the lynchpin of the argument involves technological innovation. One of the key characteristics of the theory is that the authors see continued industrial development as offering the best option for escaping from the ecological crises of the developed world. Unlike theorists who see technological development as being generally problematic —pointing to a potential need to stop capitalism and/or the process of industrialization to deal with ecological crises (see, e.g., Catton 1980; Foster 1992;

O’Connor 1991; Schnaiberg 1980; Schnaiberg and Gould 1994)—Spaargaren and Mol argue that environmental problems can best be solved through further advancement of technology and industrialization.

More speci cally, there are two main ways that the expectations of ecological modernization differ from those of most of the past work on society –environment relationships. First, the theory explicitly describes environmental improvements as being economically feasible ; indeed, entrepreneurial agents and economic/market dynamics are seen as playing leading roles in bringing about needed ecological changes. Second, in the context of the expectation for continued economic development, ecological modernization depicts political actors as building new and different coalitions to make environmental protection politically feasible .

As pointed out by a reviewer of an earlier draft of this article, changes in the performance of “the environmental state” are seen as going together logically with increasing activism among economic actors and with new roles for nongovernmental organizations. The potential for improved ecological outcomes, in short, is also seen as being dependent on changes in the institutional structure of society (see, e.g., Mol

2000a). This point is underscored by recent studies that point out the linkage between ecological modernization and political modernization (Leroy and van Tatenhove 2000;

Mol 2000b; Spaargaren 1997). In the words of Spaargaren, “the central feature of the ecological modernization approach as a theory of political modernization is its focus on new forms of political intervention” (1997, 15).

The reactions to the theory have been complex as well, ranging from the supportive to the critical, although many reactions lie between the two extremes. Perhaps the most negative reactions have come from scholars who believe that ecological modernization, or what some call “sustainable capitalism” (O’Connor 1994), is not possible. In essence, these researchers see any theory proposing such an outcome as being bound to fail (see, e.g., O’Connor 1994; see also Pellow et al. 2000). Although many of these critiques

Ecological Modernization and Its Critics 703 are rooted in a neo-Marxist perspective, others are not; a notable example involves

Anthony Giddens (1998), who argues that “ecological modernization skirts some of the main challenges ecological problems pose for social democratic thought” (p. 58) and that, as a result, the theory is “too good to be true” (p. 57; see also Leroy and van

Tatenhove 2000).

Other authors provide more nuanced criticisms. Several, for example, have concluded that the work is similar to Beck’s (1987) Risk Society (for a full discussion, see

Mol and Spaargaren 1993; see also Spaargaren 2000), although Mol and Spaargaren themselves clearly disagree, stating that the Risk Society argument “seems to fundamentally contradict ecological modernisation theory” (1993, 431). Buttel has provided a broader criticism, arguing that the theory of ecological modernization “lacks an identi able set of postulates” (2000a, 64; see also Buttel 2000b) and suggesting that the work could be improved if it were rooted in broader theories of the state, such as

Evans’s embedded autonomy (1995), or Janicke’s state failure (1990).

In addition to the critical reactions to ecological modernization, however, there have been a number of positive responses, praising ecological modernization both as a prescription and as a theory. Praise for the prescription has come from authors such as

Christoff (1996), Rinkevicius (2000a, 2000b) and O’Neill (1998). In O’Neill’s words, ecological modernization offers an innovative method for “understanding national environmental policy as embedded in changing international context” (O’Neill 1998, 2), particularly given that ecological modernization sees environmental protection not as a burden on the economy, but as “a precondition for future sustainable growth” (Weale, as cited in O’Neill 1998, 14). Much of the recent empirical research on ecological modernization consists of studies where the theory provides a degree of t for the cases (Frijns et al. 2000; Gille 2000; Jokinen 2000; Sonnenfeld 2000; see also Mol

1999). Praise for the theory has also come from theorists such as Hajer, who notes that ecological modernization “recognizes the environmental crisis as evidence of a fundamental omission in the workings of the institutions of modern society” (1995, 3).

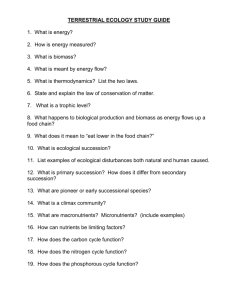

Figure 1 offers a simple graphical illustration of the views that have been expressed, with interpretations of ecological modernization as being theory and/or praxis depicted on the y axis, while the varying evaluations, from approval to dismissal, are shown on the x axis. As the gure makes clear, responses are quite diverse; the obvious question, accordingly, is, what can be done to bring greater clarity to the debates?

FIGURE 1 Interpretations of ecological modernization.

704 D. R. Fisher and W. R. Freudenburg

Toward Resolution Through Research?

With such signi cant differences in the interpretations of the theory, moving toward resolution may be no simple matter. Part of the dif culty, of course, may involve the relative newness of the work on ecological modernization. One possible response would be to follow the recommendations of Buttel (2000a), who argues that ecological modernization should be connected to more thoroughly developed theories of historical development and social change, offering the potential to get a better sense of where the new theory builds on and differs from past work and where it does not. Theoretical development in isolation, however, is likely to prove insuf cient. Instead, we believe there is also a need for theoretical development to be carried out in conjunction with empirical testing. However, it is important to recognize three other signi cant factors that, in our opinion, have played important roles in creating the vastly varying reactions to the work to date.

The rst factor is a difference nearly as stark as the cultural contrast between optimism and pessimism: As previously noted, the relatively favorable interpretations of the role of technology in ecological modernization are sharply different from those in most established theories of environment –society relationships, which tend to view technological development and economic growth as being antithetical to environmental preservation (see, e.g., Catton 1980; Dunlap and Van Liere 1978; 1984; Foster 1992;

O’Connor 1991; Schnaiberg 1980; Schnaiberg and Gould 1994). Ecological modernization perspectives, in other words, differ sharply from most established bodies of social thought, claiming that environmental improvement can take place in tandem with economic growth (for a fuller discussion of this distinction, see Fisher and Freudenburg

1999).

The second and third factors are very much interrelated. The second factor involves the potentially signi cant implications — both theoretical and practical —that follow from the differing interpretations presented by the older and newer theories. The third and nal factor is that, perhaps in part because of the theoretical and practical signi cance of the disagreements between ecological modernization and earlier bodies of thought, the debates over ecological modernization, to date, have too often been expressed in terms of black/white differences or extremes.

The rst two of these three factors— the contrasts between optimistic/pessimistic expectations and the theoretical and pragmatic importance of decisions about which view is “right” —are virtually inherent in the differences between ecological modernization and earlier perspectives. The third factor, however, is not. Although the debates between ecological modernization proponents and critics have tended to be expressed in stark, black-and-white terms, the reality is likely to be more complex —a matter of degrees, rather than of absolutes. Even based on work to date, after all, the theory’s proponents can legitimately point to cases where something like ecological modernization has taken place, and its critics can point, with equal legitimacy, to cases involving the virtual opposite. The mere accumulation of additional examples, accordingly, would seem highly unlikely to prove that one side is “right,” while the other is “wrong.”

Instead, both the theory’s proponents and its critics have met the philosophical condition of existence proof— anything that exists is possible—but it is equally clear that neither ecological modernization nor the obverse could be considered universal. The task that now faces the scienti c community is thus to work toward greater rigor in identifying conditions under which “ecological modernization” outcomes are more or less likely.

One useful step in this direction has already been provided by Cohen (1998), who has begun to ask about the conditions under which ecological modernization is likely

Ecological Modernization and Its Critics 705 to take place, examining the potential importance of factors such as institutional structure, economic organization, and especially culture (see also Cohen 2000). Cohen’s work leads him to the conclusion that a powerful public commitment to science and a strong environmental consciousness are among the most important cultural characteristics shaping individual countries’ abilities to embrace the components of ecological modernization. This work, however, is only the rst step in identifying potentially relevant conditions for ecological modernization. For the debates to move further toward resolution, this promising approach needs to be extended in two ways. First, even in cases where the focus of research is at the macro level of the nation-state, there is a clear need to expand the number of cases being considered. Second, there may also be a need to look more closely at the dynamics at work within countries.

Variations Across Nations

At the level of the nation-state, one of the major critiques of ecological modernization has to do with the applicability of the theory outside the countries in which it was created. Scholars such as Hannigan (1995) have pointed out that the theory may be reasonably appropriate for nations such as Germany and the Netherlands, where most of the theoretical development has taken place, while proving far less realistic for countries such as the United States (see also Cohen 1998). At a minimum, recent research has shown that nations do appear to vary in the degree to which institutions and outcomes of ecological modernization are evident (see, e.g., Frijns et al. 2000;

Gille 2000; Jokinen 2000; Mol 1999; Sonnenfeld 2000).

If the goal is to examine a theory in something other than black/white terms, however, it may well be necessary to use a “sample” of more than two or three countries. It is entirely possible that a theory originally developed in Germany and the

Netherlands might have been shaped by the distinctive characteristics and experiences of those nations, but at the same time, the United States could scarcely be said to be representative of the remainder of the globe—or even of other advanced countries. A number of recent cross-national comparisons have identi ed the United States as having some of the least environmentally friendly policies of all industrialized nations (see, e.g., CQ Researcher 1996; World Resources Institute 1994). If one is truly interested in identifying the conditions for and limitations of a theory, there is a good deal to be said for considering more than the few cases that may represent little more than endpoints on a continuum.

The nation of Japan, to consider a speci c example, has the world’s second largest economy, trailing only the United States, yet a number of indicators suggest that

Japan’s environmental policies may have much greater resemblance to the “ecologically modern” example of the Netherlands than to the less ecologically friendly policies of the United States. Not only have the Japanese been recognized for embracing the ISO

14,000 standard of environmental good housekeeping “faster than any other country”

( The Economist 1998, 61), but Japanese political leaders have been far more supportive of the Kyoto Protocol than have leaders in the United States. In October 1998, the

Japanese government approved the “Law Concerning the Promotion of the Measures to Cope with Global Warming” (Law Number 117 of 1998). This law “aims to promote the measures to cope with global warming through, for example, de ning the responsibilities of the central government, local governments, businesses, and citizens to take measures to cope with global warming, and establishing a basic policy on measures to cope with global warming, and thereby contribute to ensuring healthful and cultural lives of present and future generations of people, and to contribute to the welfare of

706 D. R. Fisher and W. R. Freudenburg all human beings”(w ww.eic.or.jp/eanet/e/warming.html) . To repeat our earlier point, however, although the Japanese case is telling, a mere proliferation of examples is not enough to move the debate toward resolution. The need, instead, is for careful and systematic research that considers more than the presumed extremes along a continuum.

Variations Within Nations

At the same time, there is also a need for greater attention to the factors in uencing the accuracy/inaccuracy of the theory’s predictions within a given nation-state. In our own view, in other words, we expect that ecological modernization is ultimately likely to prove neither completely correct nor completely incorrect; instead, the ultimate verdict is likely to be, “it depends.” If that is indeed the case, then it would be highly bene cial to devote a signi cantly larger fraction of our effort to studying the more speci c factors upon which it depends.

Perhaps a pair of speci c examples can help to illustrate this point. First, one possibility that has been noted in the literature is that ecological modernization logic may apply only for “developed” countries (for a full discussion, see Frijns et al. 2000).

Even the consideration of such a possibility, of course, can be seen as offering some progress toward more focused and rigorous analysis, particularly in comparison to arguments over whether the theory applies at all. In addition, however, we may nd it helpful to recognize that a concept as ill-de ned as “development” inherently involves a number of important factors, many of which can readily be translated into more negrained if not interval-level constructs, such as level of national income or strength of democratic institutions. Accordingly, we might well nd that it is possible to achieve clearer insights through empirical comparisons that show whether the theory’s predictions appear to have greater or lesser accuracy. Some examples are the differences in nations’ levels of inequality (see Boyce 1994), as well as in levels of prosperity and state repression.

Alternatively, as a second example, it is also possible to examine more closely the kinds of institutional changes that have been identi ed by the theory’s proponents as leading to improved ecological outcomes. In particular, some research has pointed to the role of nongovernmental organizations and the strength of “civil society” as a major predictor of ecological modernization outcomes —where the notion of “civil society” is generally de ned as involving a “self-organized citizenry” (Emirbayer and

Sheller 1999, 146; for a complete discussion see Cohen and Arato 1994; see also

Hann and Dunn 1996). If we return to the case of Japan, however, such an expectation might well need to be called into question. Even though Japan may come much closer to matching the predictions of ecological modernization than does the United States, the relatively progressive environmental policies of Japan have been developed in a national context that has been reported to have a virtual absence of “civil society” that informed observers have found to be remarkable (Fisher 1999; see also Knight 1996).

In sum, the theory of ecological modernization has generated a good deal of intellectual interchange and excitement to date, but much of the discussion has involved relatively generic or black-and-white disagreements. It is entirely possible to go beyond a mere repetition of such arguments, and instead to examine the theory in a way that helps us to understand the world better. To do so, however, it will be necessary to study ecological modernization in a more systematic, careful, and rigorous manner. The examples listed in this article, to repeat our warning one last time, are not intended either to “prove” or “disprove” the validity of ecological modernization;

Ecological Modernization and Its Critics 707 instead, they are intended simply to be examples, illustrating the need for further theoretical development to take place in tandem with further research. A theory that has already proved as in uential as this one, after all, surely deserves no less.

References

Beck, U. 1987. The anthropological shock: Chernobyl and the contours of the Risk Society.

Berkeley J. Sociol.

32:52 –65.

Bl¨uhdorn, I. 2000. Ecological modernization and post-ecologist politics. In Environment and global modernity , eds. G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol, and F. H. Buttel, 209–228. London: Sage

Studies in International Sociology.

Boyce, J. K. 1994. Inequality as a cause of environmental degradation.

Ecol. Econ.

11(December):169 –178.

Buttel, F. H. 2000a. Ecological modernization as social theory.

GeoForum 31:57 –65.

Buttel, F. H. 2000b. Classical theory and contemporary environmental sociology. In Environment and global modernity , eds. G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol, and F. H. Buttel, 17–40. London:

Sage Studies in International Sociology.

Catton, W. R., Jr. 1980.

Overshoot: The ecological basis of revolutionary change . Urbana:

University of Illinois Press.

Christoff, P. 1996. Ecological modernisation, ecological modernities.

Environ. Polit.

5:476 –500.

Cohen, J. L., and A. Arato. 1994.

Civil society and political theory . Boston: MIT Press.

Cohen, M. 1998. Science and the environment: Assessing cultural capacity for ecological modernization.

Public Understanding Sci.

7:149–167.

Cohen, M. J. 2000. Ecological modernization, environment knowledge and national character:

A preliminary analysis of the Netherlands. In Ecological modernisation around the world:

Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 77–107. Essex:

Frank Cass.

CQ Researcher . 1996. Global warming update: Are limits on greenhouse gas emissions needed?

6(41):961 –984.

Dunlap, R. E., and K. D. Van Liere. 1978. The “new environmental paradigm.” J. Environ.

Educ.

9(Summer):10 –19.

Dunlap, R. E., and K. D. Van Liere. 1984. Commitment to the dominant social paradigm and concern for environmental quality.

Soc. Sci. Q.

65:1013 –1028.

The Economist.

1998. Toxic waste in Japan. The burning issue. July 25:60.

Emirbayer, M., and M. Sheller. 1999. Publics in history.

Theory Society 28:145 –197.

Evans, P. 1995.

Embedded autonomy . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fisher, D. R. 1999. Testing the theory of ecological modernization: Implementation of the

Kyoto Protocol for Global Climate Change as a natural experiment. Funding Proposal to the

National Science Foundation. Copy available from author, Department of Sociology/Rural

Society, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Fisher, D. R., and W. R. Freudenburg. 1999. From the treadmill of production to ecological modernization? Applying a Habermasian framework to society –environment relationships.

Paper presented at the International Sociological Association Mini-Conference on The Environmental State under Pressure. Chicago: August.

Foster, J. B. 1992. The absolute general law of environmental degradation under capitalism.

Capitalism Nature Socialism 2(3):77 –82.

Frijns, J., P. T. Phuong, and A. P. J. Mol. 2000. Ecological modernization theory and industrializing economies: The case of Viet Nam. In Ecological modernisation around the world:

Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 257–291. Essex:

Frank Cass.

Giddens, A. 1998.

The third way . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gille, Z. 2000. Legacy of waste or wasted legacy? The end of industrial ecology in post-Socialist hungary. In Ecological modernisation around the world: Perspectives and critical debates , eds.

A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 203–234. Essex: Frank Cass.

708 D. R. Fisher and W. R. Freudenburg

Hajer, M. A. 1995.

The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hann, C., and E. Dunn. 1996.

Civil society: Challenging Western models . London: Routledge.

Hannigan, J. 1995.

Environmental sociology: A social constructivist perspective . London: Routledge.

Huber, J. 1985.

Die Regenbogengesellschaft. Okologie und Sozialpolitik . Frankfurt am Main:

Fisher Verlag.

Huber, J. 1991.

Unternehmen Umwelt. Weichenstellungen fu Eine okologische Marktwirtschart .

Frankfurt am Main: Fisher.

Janicke, M. 1990.

State failure . University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Jokinen, P. 2000. Europeanisation and ecological modernisation: Agro-environmental policy and practices in Finland. In Ecological modernisation around the world: Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 138–170. Essex: Frank Cass.

Knight, J. 1996. Making citizens in postwar Japan: National and local perspectives. In Civil society: Challenging Western models , eds. C. Hann and E. Dunn, 222–241. London: Routledge.

Leroy, P., and J. van Tatenhove. 2000. Political modernization theory and environmental politics.

In Environment and global modernity , eds. G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol, and F. H. Buttel,

187–208. London: Sage Studies in International Sociology.

Mol, A. P. J. 1995.

The re nement of production . Utrecht: Van Arkel.

Mol, A. P. J. 1997. Ecological modernization: Industrial transformations and environmental reform. In The international handbook of environmental sociology , eds. M. Redclift and

G. Woodgate, 138–149. London: Edward Elgar.

Mol, A. P. J. 1999. Ecological modernization and the environmental transformation of Europe:

Between national variations and common denominators.

J. Environ. Policy Plan.

1:167 –181.

Mol, A. P. J. 2000a. The environmental movement in an era of ecological modernization.

GeoForum 31:45 –56.

Mol, A. P. J. 2000b. Globalization and environment: Between apocalypse-blindness and ecological modernization. In Environment and global modernity , eds. G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol, and F. H. Buttel, 121–150. London: Sage Studies in International Sociology.

Mol, A. P. J., and G. Spaargaren. 1993. Environment, modernity and the Risk Society: The apocalyptic horizon of environmental reform.

Int. Sociol.

8: 431–459.

Mol, A. P. J., and G. Spaargaren. 2000. Ecological modernization theory in debate: A review.

14th World Congress of Sociology , Montreal, 24.

O’Connor, J. 1991. On the two contradictions of capitalism.

Capitalism Nature Socialism 2(3

October): 107–109.

O’Connor, J. 1994. Is sustainable capitalism possible? In Is capitalism sustainable , ed.

J. O’Connor, 152–175. New York: Guilford Press.

O’Neill, K. 1998.

Global to local, public to private: In uences on environmental policy change in industrialized countries . Paper presented at the 14th World Congress of Sociology, Montreal,

July.

Pellow, D. N., A. Schnaiberg, and A. S. Weinberg. 2000. Putting the ecological modernization thesis to the test: The promises and performances of urban recycling. In Ecological modernisation around the world: Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol, and

D. A. Sonnenfeld, 109–137. Essex: Frank Cass.

Rinkevicius, L. 2000a. The ideology of ecological modernization in “double-risk” societies: A case study of Lithuanian environmental policy. In Environment and global modernity , eds.

G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol, and F. H. Buttel, 163–186. London: Sage Studies in International

Sociology.

Rinkevicius, L. 2000b. Ecological modernisation as cultural politics: Transformation of civic environmental activism in Lithuania. In Ecological modernisation around the world: Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 171–202. Essex: Frank

Cass.

Schnaiberg, A. 1980.

The environment: From surplus to scarcity . New York: Oxford University

Press.

Ecological Modernization and Its Critics 709

Schnaiberg, A., and K. Gould. 1994.

Environment and society: The enduring con ict . New York:

St. Martin’s Press.

Sonnenfeld, D. A. 2000. Contradictions of ecological modernization: Pulp and paper manufacturing in south-east Asia. In Ecological modernisation around the world: Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 235–256. Essex: Frank Cass.

Spaargaren, G. 1997.

The ecological modernization of production and consumption: Essays in environmental sociology . Wageningen, the Netherlands: Wageningen University.

Spaargaren, G. 2000. Ecological modernization theory and the changing discourse on environment and modernity. In Environment and global modernity , eds. G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol, and F. H. Buttel, 41–72. London: Sage Studies in International Sociology.

Spaargaren, G., and A. P. J. Mol. 1992. Sociology, environment, and modernity: Ecological modernization as a theory of social change.

Society Nat. Resources 5:323 –344.

Spaargaren, G., and B. van Vliet. 2000. Lifestyles, consumption and the environment: The ecological modernisation of domestic consumption. In Ecological modernisation around the world: Perspectives and critical debates , eds. A. P. J. Mol and D. A. Sonnenfeld, 50–76.

Essex: Frank Cass.

World Resources Institute. 1994.

World resources: Guide to the global environment 1994–1995 .

New York: Oxford University Press.