Our African roots teachers pack

advertisement

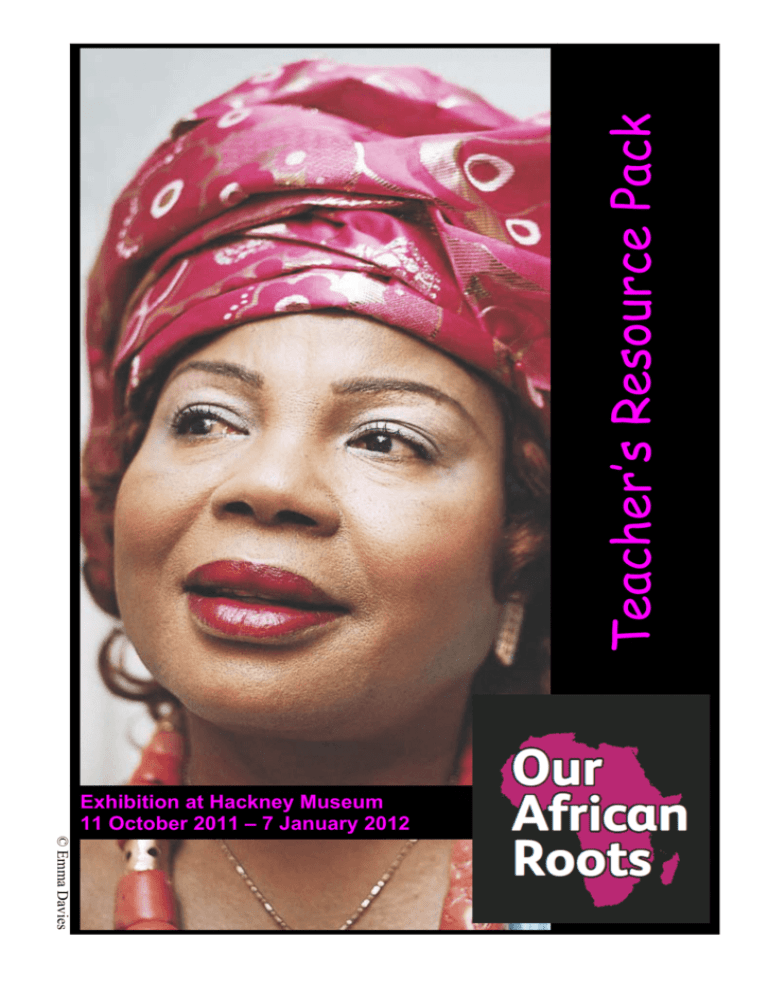

Teacher’s Resource Pack Exhibition at Hackney Museum 11 October 2011 – 7 January 2012 © Emma Davies “I’m not African because I was born in Africa; I’m an African because Africa’s born in me.” Kwame Nkrumah Hackney Museum Teachers’ Notes This pack provides you with: Ideas for teaching children about roots and identity Full colour flashcards, object cards, worksheets and resources to support learning in the classroom Activities to prepare and follow up a visit to Hackney Museum Lists of on-line resources and teaching materials to support teaching about Africa, roots and identity Contents Introduction What is the exhibition about? Curriculum links Preparing your visit to Hackney Museum What are your roots? Preparatory lesson and introductory activities Tips for preparing for a visit Following up your visit Plenary Activities; Autobiographies and Object Handling People, photographs and objects you will see during your visit Oral histories and photographs Objects and descriptions Worksheets and Further Information Worksheets to support delivery of the preparatory and follow up activities Online resources Our African Roots My roots are important to me because they teach me where I have come from, what my background is and make me be more involved in the future. I want to be a doctor and go back to my country and help out, maybe build a hospital? Debora Ntimu Born Hackney 1994 What is the exhibition about? Our African Roots is an exhibition which came about from our conversations with a number of people of African descent who live in Hackney. They generously told us their stories and lent us objects that reminded them of their African roots. Some were born here; some came to Hackney as refugees fleeing from war. Some came to join their families, others as pioneers with a spirit of adventure or a desire to better themselves. They have made a life here as well as keeping their roots in Africa. African people have lived in Hackney for at least 400 years. About 12% of Hackney’s population now have direct family links with the African continent. We asked our contributors about their background and culture, language, faith and identity. Their stories reflect Africa’s rich and sometimes troubled history from the beginnings of time to complex international connections of life here and now. We can all trace our roots back to Africa, where humanity and civilisation began. We all have a shared human experience. We all need to know our history to make sense of the world and our place in it. My The Schools Programme The programme for schools will be an opportunity for children to explore their own roots, identity and heritage against the backdrop of a wider investigation into the world wide roots of Hackney’s people. During their visit they will take part in an interactive workshop with an artist, performer, storyteller or musician who will use objects, stories, role play, folk tale, poetry or song to take them on a journey to North, East, South and West Africa. The Teachers Pack The pack has been designed to enable teachers to prepare their class for their visit and to conduct a short programme of activities exploring roots and identity with the children. The pack contains everything you need to deliver the project in class and in the museum, so you can place the museum visit within the context of a wider study of identity and the roots we share in Africa. Curriculum Links Curriculum links: x Citizenship Unit 5: Living in a Diverse World, Unit 7: Children's Rights Human Rights, x History Unit 13: Britain since 1948 x Geography: Passport to the world Intended Learning Outcomes For pupils to: x acknowledge the roots we share in Africa as the birthplace of mankind x take pride in the common heritage we all share x challenge perceptions of modern Africa and explore the similarities and differences in African countries x take responsibility for the unique role we can play in our school, family and wider community x explore the connections between where they were born and where they live now Preparing your class for their visit to Our African Roots You need to deliver some of the following activities before your visit to Our African Roots. It is essential that you use What Are Your Roots or a similar lesson so your class are aware of the themes that will be explored when they visit the exhibition and take part in the session. Other preparatory activities are optional but the more work you do with your class before you come, the more they will benefit from the session. What Are My Roots? Resources: Find resources at the back of this pack and online at www.hackney.gov.uk/museum x Tree of Life illustration x World Map x ‘I AM’ Poem x Quotes About Roots / Quotes About Africa x Patrick Vernon’s case study (Reference Sheets A, B and C) – a copy for each child or pair of children, or presented on the Interactive white board The Session What are roots? Discuss as a class or individually, in pairs or groups the following… 1. 2. Roots – ‘what do you understand the word to mean? Compose a class list entitled ‘What are my roots?’ write answers on the Tree of Life image What roots do you / your family have in Hackney? What roots do you / your family have in other parts of the UK or the world?’ Collect the children’s answers and record them on the world map. How important are your roots to you? Compose a class list entitled ‘Why are my roots important?’ (Discuss identity, discuss roots: what do the roots of a tree do? Keep the tree alive, feed the tree, hold the tree up.) What would happen if you took away the trees roots? The tree would die or fall down What would happen if someone took away your roots? You might not literally die like the tree but your sense of who you are and where you come from might die. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Poem 1. Show the class the poem ‘I AM’. This was written by a group of young people who took part in a project which explored ‘journeys’. They collectively wrote this poem to explore their own personal journeys, their roots, identities and their shared journey together as young people living and studying in Hackney today. 2. Create a similar poem for your class, each child or pair to contribute one line. Use the Quotes about Roots, Quotes about Africa and Tree of Life to inspire them to think about why roots are important to them, their family, their community. Case Study: Patrick Vernon 1. Show them Patrick Vernon’s basic profile (Patrick Vernon Reference Sheet A) 2. Remind the class that we are preparing to visit an exhibition called Our African Roots. Why do they think we are studying a man who wasn’t born in Africa to introduce the subject? Explain that his parents were not born in Africa, they were born in the Caribbean. 3. Give to the class or display on the Interactive white board Patrick Vernon Reference Sheet B & C. The children are history detectives. Ask them to go through the documents and find their own answer to the question we have just asked: Why are we using Patrick Vernon’s story to introduce an activity on Africa? 4. Discuss Africa as the birthplace of mankind Discuss Enslavement and Abolition (Refer to the website recommended in the back of this pack to introduce these subjects to your children) Plenary Draw together everything you have produced as a class to begin to discuss the importance of learning about roots and identity. Discuss with them what the exhibition is about and tell them that Patrick Vernon’s story is just one of the stories they will discover when they visit Our African Roots. Further Activities to prepare your class for their visit Introduction activity in class At school ask children about when their families moved to Hackney. You could do the following activity to introduce the idea that most or all of us have the experience of moving to Hackney: x Hands up if you were not born in Hackney. If you were born in another part of England or another part of the world? (keep your hands up) x Hands up if your parents were not born in Hackney, if your parents were born in another part of England or another part of the world? (keep your hands up) x Hands up if your grandparents were not born in Hackney, if your grandparents were born in another part of England or another part of the world? (keep your hands up – you’ll probably find all hands are up now) Then pose the question ‘what is it we all share as a class?’ (That we or our families have moved to Hackney at some point, bringing with us objects, photographs, clothes - little reminders of our roots and identities in other parts of the world). The World In One Suitcase Give the class time to explore their families experience with migration in further depth. Send the Luggage Label worksheet home for them to complete with their families. Use the information collected to create a class time-line based on when children’s families moved to Hackney. Ask the children to bring in photographs or objects which symbolise where their families have roots. Photograph the objects and ask the children to write their own captions on the suitcase worksheets – or draw their family’s objects on the worksheet to create a class display. Use Luggage Label Worksheet, Postcard Worksheet and Suitcase Worksheet at the back of this pack Mapping Memories Use the World map to mark where in the world each child’s family has moved from. Ask your pupils to pin their names on the places where their families have lived. This activity can be used to prompt discussion on who has moved the furthest or stayed in the same place the longest. Using a variety of maps means every pupil in the class can contribute to the discussion. Use World Map at the back of this pack Explore immigration in the local area As a class, make a list of all the different shops and restaurants the pupils can remember in their local area. Count the number of different nationalities and cultures which own or run the shops and restaurants. Ask children why they think this is. Ask them what it means for the borough to have lots of different nationalities settling here. Talk about the history of Hackney and the fact that lots of different groups have moved here for lots of different reasons, and this has had an influence on the businesses that exist. Practical Tips from museum staff and other teachers: to ensure your visit runs smoothly Preparing for your museum visit: x Please ensure you arrive on time for your session. If you arrive more than 10 minutes late it may not be possible to teach your class. We would prefer you to arrive at 9.55am than 10.05am. x Plan to spend 2 hours in the Museum. The taught session will last approximately 45mins - 1 hour but there will also be an opportunity for your class to take part in activities in the exhibtion. When you arrive at the Museum you will be met by a member of the Museum team who will either take you into the taught session or will show you the resources in the exhibtion. After 45mins you will swap over. x There will be 4 activities in the exhibtion space. To save time please divide them into 4 groups before your visit. Ideally you would have an adult with each group. x Bring as many Adult helpers as you can. Each adult needs to be allocated a group or two groups to supervise. Adults will be expected to ensure their group behave appropriately in the Museum, handle objects responsibly and fill in their worksheets to gain as much from the experience as possible. The activities during the visit are straightforward to deliver and all the directions the adults need are given. x Bring a camera – you are welcome to take photographs in the exhibition and in the session. Following up your visit to Our African Roots The following activities will enable you to continuing learning about Africa and exploring the themes of roots and identity in the classroom with the children. Where an activity requires worksheets you will find these at the back of the pack and online at www.hackney.gov.uk/museum F Using the Oral History Interviews Exploring autobiographies Intended Learning Outcomes For pupils to: x explore the autobiography of a particular person and build up a picture of their life x discuss and evaluate the differences between fact and fiction, biography and autoboigraphy x analyse an autobiographical text to identify key language, structure, organisation and presentational features as a preparation for writing x learn about autobiography writing and to write their own x gather information from their peers, family and wider community to create their own autobiography x recognise how their identity is shaped by where they live now but also where they or their parents might have been born Resources: x Select a suitable Our African Roots autobiography and photograph for your class – there are plenty to choose from in this pack. This session uses Maurice’s story which has been laid out as an example but you have all the information you need to use someone else’s autobiography or to compare a range of examples. You will need a copy for each child or access to an interactive whiteboard to display for the whole class to see. x Copies of the blank autobiography worksheets – one of each per child. The Session Introduction and whole-class activity: Show Maurice’s autobiography to the class. Give each child a copy of the autobiography (including photograph) or put it on the whiteboard for all to see. Read, then discuss the autobiography as a class, in pairs or groups the following… 1. Who wrote this? 2. Discuss the differences between autobiographies and biographies; first person narrative, truth and fiction, control over how your story is told and what parts of your story are kept private. 3. Why would a person choose to write about themselves rather than having someone write their biography for them? 4. Would it be an easy task? Why? Why not? Show the pupils an enlarged copy of the Maurice Information Worksheet. Go through the text again slowly with the pupils and ask them to decide which information should go into which box on the worksheet. Make notes in the appropriate box as suggested by the pupils. Model the way in which notes can be made from the text without writing whole sentences. Group activity: Give out the Maurice Information Worksheets to the pupils. Ask the pupils, in pairs, to find out as much information as they can to write up on their worksheets. Some of the information may have already been shared. Can the pupils find out anything new? Plenary: Bring the class back together again with their worksheets. Can the pupils add any additional information to what has already been recorded? Was there any contradictory information? Born Akuma, Biafra 1961 I come from a background of war, starvation, hatred. I was taught to hate from the age of five. I hated all my life and I don’t any more. Wow! How good is that! I’m happy in my own skin. I’m from Hackney but I’m also from Lakoma. I’m an Ibo man but I’m also a Rasta man. I’m a musician. I’m a human being. I’m separate from my own people, from my own culture. Our culture has been very damaged by colonialism, we have to go and claim that back. If you’ve had your history stolen you’re not a human being in the same way others are, you’re like a tree without roots and that’s not a tree at all, that’s driftwood. If you don’t know who you are, you have nothing to be faithful to. Ten years ago I had a bit of an epiphany. I became a Rasta man and somebody handed me a guitar. I discovered music; I didn’t know I could write songs. Since that time I’ve become much calmer, I’ve stopped running. We lived in a mud hut, me and my brother and my grandmother in a beautiful village called Akuma. We were like wild kids, hunting with catapults. I was five when the war started and to me that was the way the world was. When I came to Hackney my parents seemed very strange to me. I’d never really met them or seen them. I didn’t speak the language, I felt very isolated. I got knocked down quite a few times by cars. I found it really strange having to stay indoors and I’d feel hot and take all my clothes off. Because I was naked all my life I couldn’t work out what all the fuss was about. Maurice Nwokeji “Ugwumpitti is not an Ibo word. It was made up for us kids when we were in the line for food. The Red Cross used to mix cornmeal, powdered milk and water with big sticks in oil drums. We’d be hundreds of kids sitting all day with our bowls, moving up one by one, and by evening we’d get fed. Many kids just died in that queue. I’m one of the ones who made it” Waiting for Ugwumpitti © Emma Davies English and Literacy: Maurice Worksheet: Facts about me Name: Date of birth: Where I was born: Hair colour: Eye colour: Family in Africa: Childhood Memories of Africa: Childhood Memories of Hackney: Likes: Dislikes: Where are my roots?: Other interesting facts about me: Writing your own autobiography Learning Outcomes For pupils to: x take pride in the common heritage we all share x learn about autobiography writing and to write their own x gather information from their peers, family and wider community to create their won autobiography x recognise how their identity is shaped by where they live now but also where they or their parents might have been born Resources: x Copies of the blank Facts about Me worksheets – one of each per child The Session Introduction and whole-class activity: Explain that now they have investigated Maurice’s autobiography to find out facts about him, that they will now be creating their own. They will use a similar fact gathering sheet to write down facts about themselves and then will use the facts collected to write their own autobiography. Ask the pupils whether or not they think people write autobiographies on their own or whether they might have help. Take a blank Facts about Me worksheet and model the activity for the children. Explain that they will be doing additional research at home to fill in gaps but they can make a start in class. Model one or two paragraphs of an autobiography for them. Writing your autobiography Encourage the pupils to suggest vocabulary and phrases to maintain the interest of the reader. Pick out one or two sentences from the Maurice’s autobiography that may inspire the pupil's own writing. 1. What information can the pupils recall from Maurice’s autobiography? 2. Why have they remembered those points? 3. Brainstorm opening lines for the pupil's autobiographies. Group activity: Using all the information the pupils have collected so far, ask the pupils to begin writing their own autobiographies. Presenting autobiographies: Using IT: create a blank template (based on the one included at the back of this pack) for the class to create their own autobiography sheets including a photograph and key quote. Use Maurice’s as an example. Give the children a camera to take their own photograph. English and Literacy: develop basic ideas to write longer autobiographies Combine this activity with others in the pack (Suitcase, Luggage Labels. Postcards Home) to create a longer project exploring the roots and identity of the children in your class. Plenary: Ask the pupils to share opening lines. Which ones are the most powerful? Which openings would you like to read to the end? Why? This activity has been adapted from a similar activity developed by Oxfam. The Oxfam session takes Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom as the chosen text. The structure of the exercise is the same but the activity featured here has been adapted to work for the Our African Roots exhibition and has been designed for younger learners. See www.oxfam.org/ English and Literacy: Worksheet: Facts about me Name: Date of birth: Where I was born: Hair colour: Eye colour: My Family: Childhood Memories before school: Childhood Memories of school: Likes: Dislikes: Where are my roots?: Other interesting facts about me: Our African Roots: Object Handling Intended Learning Outcomes For pupils to: x critically analyse objects and understand their personal, social, political or cultural significance x scrutinise the properties of objects x broaden their vocabulary for describing objects and their properties x explore the connections between objects made abroad and objects made in the UK (materials, processes and technologies) Resources – at the back of this pack x Object sheets x Suitcase Worksheet x Luggage Labels Worksheet The Session Ask the children to bring in an object from home which… x demonstrates where their families roots lie x says something about the child’s roots and identity Questioning Materials What materials have been used to create the object? Are they expensive materials? Are the materials manmade or natural? Are the materials found in the UK? Could we find a similar material in the UK to make it? Properties Does it feel heavy or light / rough or smooth? What colour is the object? Has it been painted, decorated or adorned and how? Technologies Has the object been hand made or made in a factory? How has it been constructed? What tools have been used? Are their similar objects made in the UK? What materials and processes are used to make these in the UK? Skill How long did it take the person to make the object? Was the object made by a man, woman or child? Do you think you could make an object like this easily? Uses What is the object used for? Does it show signs of use? Has it ever been used or was it designed as an ornament never to be touched? Is there something similar that we use in the UK? Why would someone own an object like this? Related Activities Copy the Object Sheets for the class or display them on the interactive white board. Compare the children’s objects with the images of African objects. Use the questioning you did with the children’s objects to scrutinise the Museum objects, drawing comparisons and noting differences. Use the Suitcase Worksheet to create a class display about the roots and identities of the children and where in the world their family has roots. Ask the children to take home the Luggage Labels Worksheet and fill it in with their family. Ask them to draw their objects in the suitcases along with other objects they or their parents brought with them when they moved to Hackney. Further Classroom activities to follow up your visit Postcards Home Photocopy the postcards home worksheet. (one per child or group). Ask your pupils to use what they learnt at the museum during the session to imagine they were one of the people they found out about. They have just arrived in Hackney. They should then write a postcard home describing their journey and first impressions of Hackney (remind pupils of possible differences in weather, people, housing, job prospects, environment etc…) The children could design the front of the postcard according to what they think of as defining features of the borough. Extension Activity: Postcards Home Photocopy the Postcards Worksheet (one per child). Ask your pupils to use what they learnt when researching their own families moving memories to create a postcard to a relative (real or imagined) living in one of the countries of origin they discovered when speaking to their parents and grandparents. As above, telling the relative about Hackney. Moving Memories in the Community Invite someone (a parent/guardian/governor) from your local community to come and talk about their experiences of moving to Hackney – either from one of the countries covered in the session or another part of the world. Ask your pupils to think of appropriate questions to ask the visitor (they could base their questions on those used in the worksheets during the session). Mapping Memories Using photocopies of local, national and world maps ask your pupils to pin their names on the places where their families have lived. This activity can be used to prompt discussion on who has moved the furthest or stayed in the same place the longest. Using a variety of maps means every pupil in the class can contribute to the discussion. Travels with my Suitcase Photocopy the Suitcase Worksheet. Ask your pupils to think about what they would take with them if they were leaving Hackney. First of all they should make a list of some of the things that were in the suitcases in the Moving Memories museum session. Then think of 10 items they would take with them if they were leaving England and were not sure when they were coming back. Restrict to 10 items each that would fit into a small suitcase. Ask them to draw pictures of each object (remember to include clothes as well) and discuss why they have chosen each object. Your pupils should discuss/ draw the non-material things, like friends and environment that they would miss about Hackney. Kente Cloth Learn about the significance of colour used in the creation of Ghanaian Kente cloth and make your own in the classroom using scrap paper and simple materials. People, Photographs and Objects you might see in Our African Roots Use these resources to support the delivery of the lessons and activities suggested in this pack. Make sure your children are prepared for their visit and understand the exhibition is based on real people living, working and studying in Hackney today. The people featured in Our African Roots call Hackney their home but have roots in Africa and other parts of world. Some chose to come to Hackney, some have been uprooted because of war, famine or starvation. All agree on the same thing, that to know who you are and where you are going, you must have strong roots and understand where you have come from. Frank Owuasu © Emma Davies I came to Hackney in 1967 during the height of the Biafran civil war as a political refugee. That was a genocide that I will never forget, that remains under my skin. When we came here we witnessed aspects of underlying racism but I came here out of a war situation, seeing all kinds of horrific things where our own people treated us just as badly. Home is England. Our children were born here. We work here, our friends are here. So for us Hackney and the African Community School is Africa. You don’t have to go far to feel African. It’s all around us and that’s what makes Hackney so unique. It’s crucially important that we interact with other communities. Culture is transitional; if we stay locked in our culture we have to forego progress. We have a culture that segregates sexes, well I’d like to see that banished. If I picture how my mother tied me to her back and took me as a baby to the market place, I wouldn’t want my wife to do that. If you take that kind of culture, when the women do the bulk of the work, well that to me is unacceptable. What I like so much about England is equality, openness. Some of those traditional African cultures are a hindrance to our own development. I’ve seen the infighting amongst Black youths and it’s very frightening. We need to face this so if it means change, we must do it otherwise it will keep on imploding. The key to all this is education. Everyone has a right to that. For us it’s the school here – Princess May and the African School. We are proud of it, the fact that we can draw in here all sorts of different groups. We need a strong faith in ourselves, in our community. We need a clear mind, clear thoughts. We need to be open to everybody and not judge them and most important we must be willing to listen. Frank Owuasu Born Kaduna, Northern Nigeria,1956 Maurice Nwokeji © Emma Davies We lived in a mud hut, me and my brother and my grandmother in a beautiful village called Akuma. We were like wild kids, hunting with catapults. I was five when the war started and to me that was the way the world was. When I came to Hackney my parents seemed very strange to me. I’d never really met them or seen them. I didn’t speak the language, I felt very isolated. I got knocked down quite a few times by cars. I found it really strange having to stay indoors and I’d feel hot and take all my clothes off. Because I was naked all my life I couldn’t work out what all the fuss was about. Ten years ago I had a bit of an epiphany. I became a Rasta man and somebody handed me a guitar. I discovered music; I didn’t know I could write songs. Since that time I’ve become much calmer, I’ve stopped running. I’m separate from my own people, from my own culture. Our culture has been very damaged by colonialism, we have to go and claim that back. If you’ve had your history stolen you’re not a human being in the same way others are, you’re like a tree without roots and that’s not a tree at all, that’s driftwood. If you don’t know who you are, you have nothing to be faithful to. I’m happy in my own skin. I’m from Hackney but I’m also from Lakoma. I’m an Ibo man but I’m also a Rasta man. I’m a musician. I’m a human being. I come from a background of war, starvation, hatred. I was taught to hate from the age of five. I hated all my life and I don’t any more. Wow! How good is that! Maurice Nwokeji Born Akuma, Biafra, 1961 Jally Kebba Susso © Chloé Meunier There have been 74 generations of Griot musicians in my family. My child will be the 75th. I grew up with music in my house from the very beginning of my life and learnt to play the uniquely Griot instrument, the Kora. You can’t become a Griot, you are born a Griot. That’s my essence, it makes me who I am. I don’t know anything apart from music – this is what I do and I’ll do it till I die. How I play my music is very spiritual and it continues the work of my forefathers. My family passed it on to me and I will pass it on to my children. Where is home? I don’t know, you tell me. I have more friends in England than in Gambia. I’ve spent most of my adult life here. But the Gambia is where I was born and it will always be part of me. I feel blessed for I know two different worlds. I have the choice to move between them and I am free in mind to go anywhere and play my music. But my favourite place is where I am at this moment. Peace. Jally Kebba Susso Born Banjul, Gambia, early 1980s Susan Fajana-Thomas © Emma Davies My home is in Hackney. I’ve lived half of my life in Hackney and half in Nigeria but the crucial time of growing up in my twenties and thirties and now in my forties was here. I’m happy to go home to Nigeria to see my family but I see Hackney as my home; my son was born in Hackney and knows no other place. But my roots are not Hackney. I know where I come from and that makes me proud. I can trace my ancestors back at least four or five generations. We’ve got some of our heritage from America from my great, great grandmother. She was believed to be one of the liberated slaves who decided, after the abolition of the slave trade, to trace their roots back to Africa. She would use her Benin, or Yoruba name to trace her ancestors to a town called Ifon in the South west of Nigeria. We are mixed heritage in my family, that’s part of my history and that’s very important to me. Susan Fajana-Thomas Born Western State, Southwest Nigeria, 1963 Yusuf Nur Awaale © Emma Davies I came to England in 1999 from Somalia, fleeing from civil war. I was given Indefinite Leave to Remain in the UK as refugee status. In September 2000 I studied English as a Second Language at Hackney Community College and then took my degree in Accounting and Finance at London Southbank University. Hackney Community College was not just good for me, it was vital for my progress in this country. The teachers there were amazing; they really support people who want to achieve something in their lives. My friends there were from all over the world Colombia, Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria. In general life is so difficult for the first generation of immigrants in a new country; there are language barriers and culture shock. At first life here was hard for me. I wanted to quickly become integrated into this society and feel at home as a British citizen. I was only able to face these challenges because of the support that Hackney Community College gave me. Now it is my time to give back to society what society gave me. That legacy I pass on to other people who need help. Not just people from my own Somali community but others. I can help people with languages and maths. I want to keep my own Somali identity. If I don’t have my own identity as a Somali how can I help others? It is important to know your roots and your history. I want to live in this country for the rest of my life and be a role model for my children so that they can go to university here and have good careers. Yusuf Nur Awaale Born Mogadishu, Somalia, 1977 Deborah Ntimu © Arnau Oriol My parents were born in the Republic of Congo in a place called Matadi which is on the coast of Congo. I’ve never been there so I don’t know what it’s like. But I speak to my Nan and my cousin who still live in Congo and we speak French and Lingala and Kikongo at home. I’ll probably go for a visit there next year but I don’t think I’d live there unless it got cleaned up. It’s dangerous, there’s always trouble. We have lots of traditional festivals and concerts where people from my tribe, the Kikongo, come together and celebrate. We eat Congolese food such as fried plantains, barbecued goat, saltfish, cassava leaves, chicken and cassava root. We wear the Liputa headscarves. My roots are important to me because they teach me where I have come from, what my background is and make me be more involved in the future. I want to be a doctor and go back to my country and help out, maybe build a hospital? Deborah Ntimu Born Hackney, 1994 Ahmed Bockarie Kamara © Emma Davies My first impression, as somebody coming to London from a third world country to a first world country, was one of awe. I loved Hackney when I first came here. It was this melting pot of dynamism. I really thought I wouldn’t meet so many people of my colour. I was surprised that it was completely different from the way I’d imagined it. It was an eye opener. I’ve never lived in a society so metropolitan, so mixed. It made me feel at home, more at ease, more confident about myself and my prospects. Ridley Road market has been important to people of African descent by providing a wide range of ingredients used in various African Cuisines. This makes it one of Hackney’s true cultural centres. Open the Gate, the café below where I live, has been fantastic. If I’m being honest it’s a place where I feel really accepted. It’s beautiful for the community, they could have just had a restaurant there but they wanted to make it a cultural community centre. I admire them. Being away from the Gambia and Sierra Leone makes me love them even more. I miss the way we used to do things, the common things that you share when you talk to other people from Africa. For example the lights would just go off and you wouldn’t know when they were going to come back on again. In some rural areas there’s no electricity at all, but the moonlight at night is so bright. You can sit on the veranda and tell stories and you forget you’re in the dark. In the evenings we used to watch the migrating birds and they’d form these different shapes in the sky. We used to take all these things for granted and now I remember how beautiful it was. I’ve got so many friends and family here. I’m loving every bit of it. I’m still learning, still soaking it up. I wouldn’t change Hackney for the world right now. Ahmed Bockarie Kamara Born Sierra Leone, 1979 Christiana Ikeogu © Emma Davies I always think home is wherever you make it; anywhere I am I make it my home. I’ve spent more than half my life in Britain but that’s not taken me away from my cultural connections to Nigeria. Even though I’m far away I still have a huge link with my Igbo home. I think my final home is where I am eventually buried. That is because of our tradition. But I’m a Christian, so one part of me believes that it doesn’t really matter where my body is buried because it’s my soul that goes back to the Lord and that’s its proper home. But the other side of me honours the tradition set up by my ancestors that a body belongs to where it originated. So, yes I’d like to be buried in Nigeria or wherever my family finds it more convenient to do so. I leave to my beloved children to make that decision. Christiana Ikeogu Born Isulo, Anambra State, Nigeria, 1949 Felicia Okpala © Emma Davies I was born and brought up in Nigeria. I love Nigeria. I go at least once a year. I’d like to go more than that. I’d like to live there. That’s where all my relations are. If I go home now they’d all be pampering me and treating me like a queen. A goat would be killed, food cooked and all the neighbours invited into the compound. My children are here and they are good and they look after me, but for them home is Hackney; for me it’s Nigeria. That’s where my life began, that’s where I’m free. I’m proud of being who I am, a Nigerian, an African woman. Felicia Okpala Born Onitsha, Nigeria, 1952 Sandra Adufa-Appeagyei © Emma Davies I go to school in Hackney. I went out to Ghana when I was in Year 7. It was all right; there were good parts and bad parts. Some places were a proper mess, other places looked better than Hackney. There were places in Accra that looked like they could be in any European country. I liked it there because that’s what I’m used to. But it was really hot and when it rained, it rained really hard. There were flies everywhere. I understand Twi but I don’t speak it very well. I only speak it when the other person doesn’t speak English, like my grandmother in Ghana. Ghanaian people can sew really well. I love their clothes. In primary school we used to have International Day and I’d wear Ghanaian clothes and I do if I’m going to an African party. I see myself as a British girl. I don’t want to live in Ghana. Sandra Adufa-Appeagyei Born Hammersmith, 1996 Amira Kheir © Emma Davies I’ve been singing my whole life. Now I’m doing it professionally. I grew up with Sudanese music so it’s very meaningful to me. My singing taps into different Sudanese traditions but it’s not traditional in itself. I’ve reworked it so now it has bits of jazz, bits of my life and others. What comes out in my music is an adoption of what my family, my culture, my background passed on to me. I see it as spiritual, for as human beings we are all spiritual. I came to Hackney in 2004. I loved it immediately and felt so at home, so comfortable. It’s my favourite part of London. It reminded me of a lot of different places I’ve been to. It’s a place of its own, a reunion of the whole world in one area. Where I come from it’s a desert climate, very dry, where the Blue and the White Nile meet. It’s very beautiful. The Nile is the source of life there because it’s so dry. But I’m quite fluid with the idea of home. I like travelling, meeting people but I feel connected to Africa. I need to know where I come from but I don’t feel I have to stay there. It’s like a tree, if you have strong roots you can branch out and reach far. I think we have a duty to transcend culture. It’s important to know what your heritage is but not to make that a barrier between you and other people. In fact to make it a bridge that helps you to get closer to people and share and come together. I think culture should be an enabler rather than an impediment, especially as we all have different cultures. That’s what I feel about Hackney; in its own little way it’s an example of that. Amira Kheir Born Turin, Italy, 1985 Originated from Khartoum, Sudan Apostle Ben Kaye © Emma Davies One amazing thing is that we were able to establish this Ministry not from inside the walls of the Church but from Hackney Marshes. For me Hackney is a very important place in everything that we have been able to achieve. The calling came to me whilst I was in the field on Hackney Marshes. The Lord opened my eyes. He is the root cause of all the work we do here, the flexibility that exists around this Hackney. We started this ministry from the field. We had nothing; we were praying. Where else in the world would it be possible to get down in the field and pray without interference? Once I remember the police came with helicopters to see what was happening in the dark there and when they saw we were praying they just said to carry on with the good work. So if you come here and you are serious and know exactly what you want to do, then Hackney is a place full of avenues and opportunities. People call me God’s general because what we do here is tough. We always have to be in prayer to sustain the power of God to help people. That is the mandate God has given us and we have to fulfil it. I could not have done that if I had not been in Hackney, on the Marshes for two and a half years, in all weathers, wind and snow, late into the night, praying, praying, praying. I cannot leave the commitment God has given me. God led me to the field. I cannot leave Hackney without the leading of the Lord. It is a serious task the Lord has given us to do and we must do it. We must always be led by the Lord and when a man walks in this way there is nothing he cannot do. Apostle Ben Kaye Born Cape Coast, Ghana, 1964 Patrick Vernon © Emma Davies I took a DNA test to find the African side of my family history after some documentary research. Mitochondrial DNA test provides invaluable data of one’s chromosomal, a genetic footprint that can be matched with similar results around the world. This DNA is passed down almost unchanged from generation to generation on the maternal line. Scientists believe that this DNA can be ultimately traced back to one woman who lived around 150,000 years ago and who is commonly referred to as Mitochondrial Eve in Africa. My result pinpointed to a village called Kedougou in Senegal. I went there to trace more of my family history, first to the Roots Festival in Gambia and then on to Dakar in Senegal. Roots give you a sense of identity. By tracing my family history I learnt a lot about myself, I felt validated, located into world history and into Britain, London and therefore Hackney. It gave me a context; migration, colonisation, globalisation. I think that if we have historical understanding of the past then we can link that to contemporary issues that face us living in Hackney today. It’s about belonging. I think we all need that sense of belonging. Young people need a sense of belonging especially in a changing, uncertain globalised world. I believe that if all young Black people could go and stand in the slave forts on the east and west coasts of Africa they would have a better understanding of their history, of what their ancestors went through as well as the significant contribution that people of African descent have made throughout world history. They would have a clearer understanding of their roots. And this might then make a real difference to the issues around violence and knife crime. Patrick Vernon Born Wolverhampton, 1961 Toyin Agbetu © Emma Davies I’m a Pan Africanist. I embrace the reality that throughout world history African people have been dispersed all across the Earth. My parents were born in Africa, my wife has Caribbean heritage, because of our roots, my children, according to the census, are ‘mixed race’. That’s nonsense. We are all Africans belonging to a global Pan African family. So first and foremost my primary identity is that of being an African. When anyone looks at me, that’s the first thing they see. Fully embracing my identity links me to the Motherland, to history and traditions that go back to the beginnings of human kind. After that I would say I am Yoruba. I’m also a bloke, I’m a man who is a human rights activist. I’m also a Hackneyite. I was born here, I work here. I’m not planning to leave until I’ve done my best to challenge the inequality and prejudice caused by social maldevelopment. If culturally aware education can offer social justice and freedom for all in Hackney, then I believe we can replicate those ideas as solutions elsewhere. My culture is not a separate part of me. It’s what I breathe; it forms the very essence of who I am. Those communal traditions and rituals are engrained in my everyday life. When I was growing up I was never in any doubt as to who I was. We ate traditional foods, listened to African music, my father taught us that a good life was about family and collaboration with others, not individualism and competition. We were a bicultural entity in a world with different values and often that entity faced attacks creating pressure on it to become submerged, hidden in order to survive. Language remains the key. It transports culture, cements communities. It’s like an island of history, an island of our Ancestors, of our achievements, our ideas, our dreams but also our tales of woe. I speak a little Yoruba to my children on a basic level but I struggle to learn to use it fluently for myself. African enslavement, colonisation or Maafa meant that we were taught that African languages were bad and somehow inferior to others. Even in today’s Britain there’s hostility directed towards those who choose to speak using our mother tongues in favour of English. Yet despite this it remains my ambition to fully learn at least three African languages – Yoruba, Kiswahili and perhaps the ancient Kemetic tongue. Toyin Agbetu Born Hackney, 1967 Rattle / shaker (Axatse, Shekere, lilolo) Made from two hollowed out gourds (the smaller bulb serves as a handle). Each gourd is hand-picked for its roundness and long handle. A hole is cut in one end and the fibrous material and seeds are removed. The remaining hard, thin gourd shell resonates differently depending on the type of bead (cowrie shells or seed) used by the maker. Handcrafted in Africa, each one is a small work of art. From Ghana / Nigeria Thumb Piano (Kalimba, mbira or likembe) The thumb piano was typically played while walking by travelling Griots, African poet who keep alive the history of the tribe or village, and to entertain people with songs, stories, poems and dances. (See Jally Kebba Susso who features in the exhibition for more information about Griots. He plays the Kora) Talking Drum (Dondo, Mande Dunun, Gangan, Sangban, Kenkeni , Akan Fontomfrom, Ngoma) Wooden base with goat or cow skin. Talking drums from Ghana and the Yoruba region of Nigeria, are variable-pitch drums played with a curved stick by squeezing it under the player's arm. For photos of drums being handcrafted in Africa see: http://www.motherlandmusic.com/drums.htm Headwrap known as 'Duku' (Malawi, Ghana), 'Dhuku' (Zimbabwe), 'Tukwi' (Botswana) and 'Gele' (Nigeria) Historically, meanings were given to the way a “Gele” was wrapped an great care is taken to wrap the gele on a woman’s head properly (see videos on Youtube). To West African women the gele is more than just an fashion accessory and the fabric and colours have different meanings. This gele belongs to Christiana Ikeogu who features in the exhibition and is from Nigeria. Fulani or wodaabe hat Made from leather and fibre and sometimes embellished with cowrie shells. Worn as a shield against the harsh African sun and during time of celebration or festivity. From Mali and West Africa Chess Pieces Hand carved wood (other materials used are soapstone, ebony, ivory and Malachite stone) Each chess set is an original work of art, individually handmade, meaning no two are exactly alike. Some depict ancient kingdoms of Africa, some have African animals, others show two tribes at war. Gold Weights, Ghana (18th / 19th Century) These Ashanti weights are from Ghana and show two men with tools and weapons. The weights are made from brass and were used as counter weights for weighing gold, the currency of Ghana at the time. The weights were banned in Ghana when the use of gold-dust as currency was outlawed in 1894. Pestle and Mortar Hand carved wood Used for pounding corn, betel root, cassava root, yam, herbs and spices Nigeria Drinking Vessel Hollowed out gourd (like a pumpkin) used for carrying water and other liquids Nigeria Bowls Hollowed out gourds (like a pumpkin) which are pyro-etched (decorated using burning and scratching) and adorned with beads. Used for food, liquids and carrying things. The rope base makes the rounded gourd bowl sit upright on the ground. AYO GAME BOARD (OPON AYO) FROM SOUTH WESTERN NIGERIA The 'Ayo board’ is made from wood and 48 seeds and it is usually played by 2 people. x x x The game starts by placing 4 seeds in each of the 12 cups on the board, and each player sits with 6 of the cups on their side of the board. For each turn, a player chooses a cup, takes all the seeds in that cup (it will the 4 seeds for the first player, but it may be more or less as the game continues), and goes around the board in a counter clockwise direction, planting one seed in each cup as they go. If your last seed lands in your opponent's cup, you can capture all the seeds in that cup, and add it to your bank, unless is 4 or more in the cup. The game continues until one player cannot move, at which point, the one with the most seeds wins. Handmade Doll This doll was given to us by a lady whose parents travelled all over Africa collecting interesting things. She doesn’t know where they found this doll but we think it was probably made by a young girl using materials found in Africa. Worksheets and Further Information Use the worksheet templates and information sheets to support delivery of the lessons and activities outlined in the pack. The Tree of Life by Silondile Jali “A tree with solid roots will flower many fruits” Silondile Jali describes herself as a “young fresh spirit incarnated as graphic designer who was born eThekwini (Durban, South Africa) and is inspired by all things bright and prettie”. Find out more at: http://childofcolour.wordpress.com/2008/11/17/tree-of-life/ World Map I Am I am Old with a young heart, with music pumping through my veins. A volcano, dormant for most of my life but only looked upon when I erupt. A hedgehog. I protect myself only when threatened. A minibus. Small but holds many. A pineapple. Strong on the outside but sweet on the inside. A big band, with many different sounds, rhythms and melodies coming together to make the sweetest sound. A diamond, precious and valuable. A museum full of history and holds many cultures. A rainbow. Who am I? I am Hackney. By Clinton Avbioroko, Taslim Choudhury, Bruno Ferreira, Gladi Mayisa and Joel Toney Year 10 pupils from Hackney Free and Parochial School It’s about belonging. I think we all need that sense of belonging. Young people need a sense of belonging especially in a changing, uncertain globalise world. I believe that if all young Black people could go and stand in the slave forts on the east and west coasts of Africa they would have a better understanding of their history, of what their ancestors went through as well as the significant contribution that people of African descent have made through world history. They would have a clearer understanding of their roots. And this might then make a real difference to the issues around violence and knife crime. Patrick Vernon Born Wolverhampton, 1961 My home is in Hackney. I’ve lived half of my life in Hackney and half in Nigeria but the crucial time of growing up in my twenties and thirties and now in my forties was here. I’m happy to go home to Nigeria to see my family but I see Hackney as my home; my son was born in Hackney and knows no other place. But my roots are not Hackney. I know where I come from and that makes me proud. I can trace my ancestors back at least four or five generations. We’ve got some of our heritage from America from my great, great grandmother. In those days in Africa after the slave trade, my grandfather used to tell me that people wondered where she came from because she was so different from other people. She was one of the liberated slaves who decided, after the abolition of the slave trade, that she would use her Benin, or Yoruba, name to trace which country she came from. That’s part of my heritage and my history and that’s very important to me. Susan Fulani-Thomas Born in Ekiti State, southwest Nigeria in 1963 I was born and brought up in Nigeria. I love Nigeria. I go at least once a year. I’d like to go more than that. I’d like to live there. That’s where all my relations are. If I go home now they’d all be pampering me and treating me like a queen. A goat would be killed, food cooked and all the neighbours invited into the compound. My children are here and they are good and they look after me, but for them home is Hackney; for me it’s Nigeria. That’s where my life began, that’s where I’m free. I’m proud of being who I am, a Nigerian, an African woman. My roots are important to me because they teach me where I have come from, what my background in the Democratic Republic of Congo is and make me be more involved in the future. I want to be a doctor and go back to my country and help out, maybe build a hospital? Felicia Okpala Born Onitsha, Nigeria , 1952 I wanted to keep my own Somali identity. If I don’t have my own identity as a Somali how can I help others? To face these challenges you need to know who you are, you need to know your roots and your history. If you know yourself better you can therefore become a better human being. You need to work hard and learn what can help you so that you can help the rest of the community and the wider society. Debora Ntimu Born Hackney 1994 Quotes about Roots Yusuf Awale Born in Mogadishu, Somalia 1977 We have lots of traditional festivals and concerts, where people from my tribe, the Kikongo, come together and celebrate. We eat Congolese food such as fried plantains, barbecued goat, saltfish, cassava leaves, chicken and cassava root. We wear the Liputa headscarves. We lived in a mud hut, me and my brother and my grandmother in a beautiful village called Lakoma. We were like wild kids, hunting with catapults. I was five when the war started and to me that was the way the world was. “Ugwumpitti is not an Igbo word. It was made up for us kids when we were in the line for food. The Red Cross used to mix cornmeal, powdered milk and water with big sticks in oil drums. We’d be hundreds of kids sitting all day with our bowls, moving up one by one, and by evening we’d get fed. Many kids just died in that queue. I’m one of the ones who made it” Maurice Nwokej (IJah) Born Biafra, 1961 Sandra AdufaAppeagyei Born in Hammersmith, 1996 I go to school in Hackney. I went out to Ghana when I was in Year 7. It was all right; there were good parts and bad parts. Some places were a proper mess, other places looked better than Hackney. There were places in Accra that looked like they could be in any European country. I liked it there because that’s what I’m used to. But it was really hot and when it rained, it rained really hard. There were flies everywhere. Being away from the Gambia and Sierra Leone makes me love them even more. I miss the way we used to do things, the common things that you share when you talk to other people from Africa. For example the lights would just go off and you wouldn’t know when they were going to come back on again. In some rural areas there’s no electricity at all, but the moonlight at night is so bright. You can sit on the veranda and tell stories and you forget you’re in the dark. In the evenings we used to watch the migrating birds and they’d form these different shapes in the sky. We used to take all these things for granted and now I remember how beautiful it was. Ahmed Bockarie Kamara Born Sierra Leone, 1979 Where I come from it’s a desert climate, very dry, where the Blue and the White Nile meet. It’s very beautiful. The Nile is the source of life there because it’s so dry. But I’m quite fluid with the idea of home. I like travelling, meeting people but I feel connected to Africa. I need to know where I come from but I don’t feel I have to stay there. It’s like a tree, if you have strong roots you can branch out and reach far. Debora Ntimu Born Hackney 1994 I was born and brought up in Nigeria. I love Nigeria. I go at least once a year. I’d like to go more than that. I’d like to live there. That’s where all my relations are. If I go home now they’d all be pampering me and treating me like a queen. A goat would be killed, food cooked and all the neighbours invited into the compound. My children are here and they are good and they look after me, but for them home is Hackney; for me it’s Nigeria. Amira Kheir Born 1985 Turin, Italy, Originated from Khartoum, Sudan Quotes about Africa Felicia Okpala Born Onitsha, Nigeria , 1952 Suitcases Worksheet Postcards Home Worksheet Stick stamp here My name is I was born in My parents were born in My grandparents were born in 1990s 1950s 2000 My great grandparents were born in My family moved to hackney in My family moved to Hackney because My family brought these things in their suitcase 1940s 1980s Luggage Label Worksheet 1930s 1970s 1920s 1960s Exploring Africa Where to start? Perspectives on Africa For use in the classroom Teachers TV has a range of online resources for you to use in the classroom x A power point presentation on Nelson Mandela and the struggles in South Africa. It is targeted at KS1 and part of the Famous People unit: http://www.tes.co.uk/teachingresource/Nelson-Mandela-Power-Point-Presentation-3006246/ x An “Interview" with Mansa Musa, emperor of the Mali Empire 1312–1337CE. Providing opportunities for discussion about African Empires before the Slave Trade. Encourages pupil engagement and features additional information about Mansa Musa and weblinks about more recent figures from black history. Taken from Black History: African Empires, written by Dan Lyndon and published by Franklin Watts. http://www.tes.co.uk/teaching-resource/Black-History-African-Empires-6060701/ For your own research purposes The National Maritime Museum have detailed and comprehensive histories targeted at KS4 and adults which are available online to help you to prepare for teaching about Africa. x An introduction to ancient African kingdoms http://www.understandingslavery.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=377&Itemid=232 x Africa before slavery http://www.understandingslavery.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=306&Itemid=151 x The lost libraries of Timbuktu http://www.understandingslavery.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=378&Itemid=233 Lesson Plans and classroom resources Oxfam has fantastic resources for teaching about Africa and the world. www.oxfam.org The site below has a fantastic and interactive map of Africa. You can click on different areas of the map and it will take you to a page with facts and information about the area you have clicked on. http://artnetweb.com/guggenheim/africa/africamap.html Exploring Enslavement and Abolition For your own research purposes: The National Maritime Museum have detailed and comprehensive histories targeted at KS4 and adults which are available online to help you to prepare for teaching about Enslavement and Abolition. Please ensure you examine these resources carefully before showing them to your children as these have been designed for much older learners. x Africa before slavery http://www.understandingslavery.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=306&Itemid=151 For use in the classroom with KS2 children: Visit the Hackney Museum Learning pages at www.hackney.gov.uk/museum to download a copy of Abolition 07. These resources were developed to support a programme of events for schools to commemorate 200 years since the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade but they contain a wealth of materials for teaching about enslavement and abolition. Objects of Resistance Hackney Museum From the first slave ship to leave British shores in 1562 to the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, at Hackney Museum you can discover the role of Britain in the transatlantic slave trade through stories and belongings of the British and African people who campaigned and fought for its abolition. This FREE session is available throughout the year so book now for your KS2 class. Exploring Rig and Immigration Exploring Rights, Responsibilities Amnesty International Information about joining the Junior Urgent Action Campaign for 7 – 11 year olds http://www.amnesty.org.uk/content.asp?CategoryID=773&ArticleID=773 Save the Children Resources exploring issues around children’s rights. http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/assets/php/library.php?Type=Teaching+resources UNICEF UK Tagd Information about children’s rights in the UK http://www.tagd.org.uk/beinformed/rights/aboutrights.aspx UNICEF Information about teaching children about their rights http://www.unicef.org.uk/tz/rights/teaching_rights.asp The British Red Cross A lesson plan and resources addressing issues of migration. It is based on recent events when migrants from Africa arrived on a beach in the Canary Islands. http://www.redcross.org.uk/standard.asp?id=74545 Moving Here A website with information and resources about immigration into England for the last 200 years which aims to involve minority ethnic groups in the recording of their own history. It has a special section for schools which includes ideas, resources and games. http://www.movinghere.org.uk Refugee Week Explore the meaning of ‘refuge’ with your class. The Refugee Week website has a lesson plan to introduce this topic: http://www.refugeeweek.org.uk/simple-acts/toolkit/schools/lesson-plans/LessonPlan-learn-five-facts Born Wolverhampton, 1961 Patrick Vernon Patrick Vernon Reference Sheet A © Emma Davies Patrick Vernon Reference Sheet B Patrick Vernon Patrick Vernon Reference Sheet C It’s about belonging. I think we all need that sense of belonging. Young people need a sense of belonging especially in a changing, uncertain globalised world. I believe that if all young Black people could go and stand in the slave forts on the east and west coasts of Africa they would have a better understanding of their history, of what their ancestors went through as well as the significant contribution that people of African descent have made throughout world history. They would have a clearer understanding of their roots. And this might then make a real difference to the issues around violence and knife crime. Roots give you a sense of identity. By tracing my family history I learnt a lot about myself, I felt validated, located into world history and into Britain, London and therefore Hackney. It gave me a context; migration, colonisation, globalisation. I think that if we have historical understanding of the past then we can link that to contemporary issues that face us living in Hackney today. My result pinpointed to a village called Kedougou in Senegal. I went there to trace more of my family history, first to the Roots Festival in Gambia and then on to Dakar in Senegal. I took a DNA test to find the African side of my family history after some documentary research. Mitochondrial DNA test provides invaluable data of one’s chromosomal, a genetic footprint that can be matched with similar results around the world. This DNA is passed down almost unchanged from generation to generation on the maternal line. Scientists believe that this DNA can be ultimately traced back to one woman who lived around 150,000 years ago and who is commonly referred to as Mitochondrial Eve in Africa. Born Akuma, Biafra 1961 I come from a background of war, starvation, hatred. I was taught to hate from the age of five. I hated all my life and I don’t any more. Wow! How good is that! I’m happy in my own skin. I’m from Hackney but I’m also from Lakoma. I’m an Ibo man but I’m also a Rasta man. I’m a musician. I’m a human being. I’m separate from my own people, from my own culture. Our culture has been very damaged by colonialism, we have to go and claim that back. If you’ve had your history stolen you’re not a human being in the same way others are, you’re like a tree without roots and that’s not a tree at all, that’s driftwood. If you don’t know who you are, you have nothing to be faithful to. Ten years ago I had a bit of an epiphany. I became a Rasta man and somebody handed me a guitar. I discovered music; I didn’t know I could write songs. Since that time I’ve become much calmer, I’ve stopped running. We lived in a mud hut, me and my brother and my grandmother in a beautiful village called Akuma. We were like wild kids, hunting with catapults. I was five when the war started and to me that was the way the world was. When I came to Hackney my parents seemed very strange to me. I’d never really met them or seen them. I didn’t speak the language, I felt very isolated. I got knocked down quite a few times by cars. I found it really strange having to stay indoors and I’d feel hot and take all my clothes off. Because I was naked all my life I couldn’t work out what all the fuss was about. Maurice Nwokeji “Ugwumpitti is not an Igbo word. It was made up for us kids when we were in the line for food. The Red Cross used to mix cornmeal, powdered milk and water with big sticks in oil drums. We’d be hundreds of kids sitting all day with our bowls, moving up one by one, and by evening we’d get fed. Many kids just died in that queue. I’m one of the ones who made it” Waiting for Ugwumpitti © Emma Davies Craft Activities Kente Cloth Designs Learning Outcomes: For children to: x acknowledge the significance of Kente cloth to Ghanaian culture and to understand the meanings and symbolism x make their own brightly patterned kente cloth out of paper and pens, pencils or paints x use fine motor skills to draw geometric shapes as well as colour, cut and paste strips of “cloth” together. x recognise the differences between geometric and organic shapes and lines. Resources: x x x x x x x x x Kente cloth fact sheet White paper Pens, pencils, paints Samples of kente cloth images or real samples Scissors Pieces of mount board, 13” x 12” Glue Samples of Kente cloth (fabric shops, Ridley Road Market– maybe children in your class can bring some in from home) Copies of Kente cloth images from the pack or from the internet The Session: Instructions: Use the fact sheet, images and samples to discuss with the class the significance of kente cloths and how they are made. Ask them which designs they like and discuss the difference between geometric and organic shapes and lines and the significance of colours. Use the finished samples to create a display on Kente, or as the background for a class display on Africa Trace the design of the kente cloth that has been chosen and use this detailed pattern to draw directly onto your paper Kente. Stick them onto the strips in the desired pattern Cut the shapes out. Use pencils and rulers to design geometric patterns of stripes, squares, diamonds, triangles on sugar paper. Refer to the original kente cloth samples and use the shapes and patterns as inspiration for their own. Glue the base strips onto mount board or an A4 piece of sugar paper Use a variety of colours to create the base of your kente design. Cut along the lines. On A4 pieces of paper measure and mark four 10cm x 30cm strips. Making Kente cloth in the classroom Where is it from? Most examples of Kente cloth are from Ghana, but the fabric is worn across Africa, Europe, America, and Asia by people of African heritage. Kente is pan African . x x x x x x x x x x x x Black – maturation, intensified spiritual energy Blue – peace, harmony and love Green – vegetation, planting, harvest, growth Gold – royalty, wealth, high status, glory Grey – healing and cleansing Maroon – the colour of mother earth, healing Pink – feminine Purple –feminine; usually worn by women Red – political, fighting, war, bloodshed, death Silver – serenity, purity, joy; associated with the moon White – pure, festive occasions Yellow – precious, royalty, wealth Symbolic Meanings of the Colours in Kente Cloth: When is it worn? Kente cloth is used in: Celebrations: Weddings, Births, Graduations, Ceremonies to bring in new leaders; Whenever you want to respectfully show your African heritage. Kente Cloth Fact Sheet How is it made? Kente is by hand weaving strips of cloth on a loom and sewing them together using geometric designs to create larger pieces of cloth. Symbol: SANKOFA Pronounced: sang-ko-fah Literal meaning: go back to fetch it Symbol of the wisdom of learning from the past to build for the future Symbol: MATE MASIE Pronounced: mah-tee mah-see-uh Literal meaning: what I hear, I keep, I understand Symbol of wisdom and knowledge Symbol: HYE-WO-NHYE Pronounced: she –wo –n-shee Literal meaning: unburnable Symbol of toughness or resistance Adinkra symbols Adinkra symbols are used in West African societies, particularly by the Akan people of Ghana. Symbol: FUNTUMMIREKUDENKYEMMIREKU Pronounced: fun-tum-me-rek-koo Den- chim-me-rek-koo Literal meaning: a Ghanaian Mythical creature Symbol of unity in diversity, democracy or oneness of the human family despite cultural differences and diversities Symbol: NKONSONKONSON Pronounced: corn-song-corn-song Literal meaning: a chain or a link Symbol of unity, responsibility, interdependence, brotherhood and cooperation Symbol: EPA Pronunciation: eh-paw Literal meaning: handcuffs Symbol of law and justice Booklist African Folktales x African Folk Tales by Hugh Vernon-Jackson. Eighteen authentic fables recorded as they were told by tribal members of Nigerian and other cultures complete with lively illustrations. x The Adventures of Spider: West African Folktales by Joyce C Arkhurst. The storyteller brings to life a favourite character from West African folklore- the mischievous and clever spider. x Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti by Gerald McDermott. In Ashanti land, the story of Anansi is a beloved folk tale. Animal Tales x x x x A Twist in the Tail: Animal Stories from Around the World by Mary Hoffman and Jan Ormerod. Ten delightful stories bring together animal characters from all over the globe. Suitable for KS 1- 2 English. Once Upon a Time In Ghana: Traditional Ewe Stories Retold in English by Anna Cottrell. A collection of original and traditional stories from Ghana. This is the Tree: A Story of the Baobab by Miriam Moss and Adrienne Kennaway. The ancient and curious baobab tree is the centre of this book about the wildlife of the wide African plain. We All Went on Safari: A Counting Journey Through Tanzania by Laurie Krebs. Join a group of friends as they set out on a counting journey through the grasslands of Tanzania. Along the way they encounter all sorts of animals while counting from one to ten in both English and Swahili. Culture and Tradition x x x . The Spider Weaver: A Legend of Kente Cloth by Margaret Musgrove and Julia Cairns. The story in this book is widely known among the weavers in Ghana and dates back to the mid-seventeenth century. Many patterns woven in kente cloth have significance. Ghana (Countries of the World) by Lucile Davis. This book provides an introduction to the geography, history, natural resources, culture, and people of the West African country of Ghana. Kente Colors by Deborah Newton Chocolate. Rhythmic verse shows the special meaning of colours and patterns while glorious paintings show kente as it is used and worn in Ghana. Booklist Enslavement and Abolition x x x x x x x x x Who was Harriet Tubman? by Yona Zeldis McDonough. A biography of the 19th Century woman who escaped slavery and helped many other slaves get to freedom on the Underground Railroad. KS 1-3 The Kidnapped Prince: The Life of Olaudah Equiano by O. Equiano (Adapted by Ann Cameron). Black Settlers in Britain 1555-1958 by Nigel File and Chris Power. A history of black people in Britain including newspaper extracts, paintings, prints and photographs. Why are People Different? by Susan Meredith. This provides an introduction with lots of information to help answer children’s questions about the world around them. The Carpet Boy’s Gift by Pegi Deitz Shea. Based on a true story provides ideas for activities based around modern slavery around the world. History of the African and Caribbean Communities In Britain by Hakim Adi. A well illustrated history of this community and its contribution to life in Britain including lots of material on the British slave trade. KS 1-3 Sweet Clara and The Freedom Quilt by Deborah Hopkinson. A lovely fictional account of the people who made quilts to tell their stories, and to communicate messages to each other in slavery in America. KS 1-2 Amistad: the Story of a Slave Ship by Patricia C McKissack. This illustrated book tells the story of the brave kidnapped people onboard the slave ship who rebelled and refused to give up their freedom. KS 1-3 Amazing Adventures of Equiano by Jean-Jaques Vayssieres. A graphic novel, published in Jamaica that follows the story of Equiano from his home in West Africa, across the sea. KS 2 This pack was researched and written by Emma Winch, Schools and Families Learning Officer Hackney Museum. Interviews with participants by Sue McAlpine Transcripts and session research by Suzanne Wright Photographs of the contributors by Emma Davies and Arnau Oriol Objects have been kindly loaned by the Horniman Museum and Ann Wheelhouse I would like to say thank you to everyone who has contributed a story, photograph or object or idea to the exhibition, education pack or schools programme: Diana Olutunmogun Valentine Hanson Helen Marcia McDonald Maurice Nwokeji Frank Owuasu Sandra Adufa-Appeagyei Yusuf Nur Awaale Susan Fajana-Thomas Christiana Ikeogu Jally Kebba Susso Felicia Okpala Debora Ntimu Toyin Agbetu Ahmed Bockarie Kamara Apostle Ben Kaye Patrick Vernon Amira Kheir Baden Price Jnr Silondile Jali for the Tree of Life Linda Sydow Violet Koska Black Elizabeth Fraser Betts Oliver Petts