Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

Working Paper Proceedings

Engineering Project Organizations Conference

Rheden, The Netherlands

July 10-12, 2012

Learning for Win-Win Cooperation

Jiin-Song Tsai and Cheryl Chi

Proceedings Editors

Amy Javernick-Will, University of Colorado and Ashwin Mahalingam, IIT-Madras

© Copyright belongs to the authors. All rights reserved. Please contact authors for citation details.

1

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

LEARNING FOR WIN-WIN COOPERATION

Jiin-Song Tsai,1 and Cheryl S.F. Chi 2

ABSTRACT

This paper presents an experimental study that explores a learning process in which a series of

games was conducted in the classroom encouraging students to practice the win-win strategy by

resolving the difficulties and disputes within and between small groups. In total, thirty-two

engineering students were teamed up in groups of four. Their personal properties and conflict

management styles were measured with questionnaires of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

(MBTI; Keirsey 1998) and the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI; Kilmann and

Thomas 1977), respectively. They were asked to accomplish the designated tasks in three games:

(1) intra-group joint decision making to deal with the threat of a natural disaster, (2) negotiation

between two groups to deal with their inter-group competition, and (3) cooperation with a

competitor group to achieve an inter-group win-win for mutual gains. The purpose of games is to

observe two types of learning mechanisms: single-loop and double-loop learning models

(Argyris and Schön 1996). A control group composed by another thirty-two students of business

major joins the experiment in the third game. The specific goals for group members to achieve

are: (1) the first game aims to develop their patterns of joint decision-making; (2) the second

game is to learn the consequence of zero-sum competition; (3) the third game is to perform

cooperative actions with a new group of students under the prison’s dilemma. The preliminary

findings indicate that (1) the positive outcomes of group learning through the experiment; (2) the

single-loop learning is repeated a number of times in the prisoner’s dilemma game; (3) the

double-loop learning was driven by needs for getting out of the paradoxical trap to achieve

mutual gains. The measurements of MBTI and TKI seem to be correlated with each other but not

sufficient to be discussed in this paper yet.

KEYWORDS: Learning, collaboration, conflict management, trust building

1. INTRODUCTION

Collaboration has been emphasized as a crucial factor influencing project performance.

It contributes to effective problem-solving, facilitates risk-sharing, and provides flexibility and

responsiveness in the face of uncertainties that characterize construction projects (Rahman &

Kumaraswamy, 2002). Inter-organizational collaboration through trust-based partnership reduces

transaction and monitoring cost and encourages resource and risk sharing (Gulati 1995; Uzzi

1997). This is especially challenging for participants of public construction projects who have to

work under hierarchical and regulatory requirements for fairness, objectivity, transparency, etc.,

which leaves little room for trust-based partnership and relational contracting (Bradach and

Eccles 1989). In addition, the possibility for disputes and conflicts in public construction

contracts is increased by the complexity and the scope of the contract and its subject matter.

Nevertheless, trust-based cooperation can be developed at interpersonal level.

Interpersonal interaction and communication between managers representing different project

1

Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, ROC.

jstsai@mail.ncku.edu.tw

2

Postdoctoral Researcher, Center for Industrial Development and Environmental Governance, School of Public

Policy and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 100084, cheryl.sfchi@gmail.com

2

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

parties play a major role in reducing the perceived risk regarding whether other parties will act

opportunistically (Ceric 2011) and thus directly affect trust building across boundaries.

Managers’ interpretations of conflicting issues directly link to their responses to these issues

(Dutton and Jackson 1987). Therefore, the interpretative frames that individuals “bring to make

sense of what others are doing” (Fligstein and McAdam 2011: 4) determining the meanings

attached to conflicting issues that lead to a certain set of actions rather than other possible actions

(Dutton and Jackson 1987). Backmann (2011) posits that such interpretive frames can be swiftly

and actively created or changed in an institutional environment where people are encouraged to

trust each other by working together to achieve a common goal, and meanwhile learning together

to reach a conceptual understanding. For example, a education program which channels the

behaviors of actors into certain directions through a learning process for increasing the overall

level of trust in a specific system.

Inspired by the lines of research, this study attempts to explore how learning

(representing a social nurturing process) and conflict management styles (representing individual

propensities) affects collaborative attitude. Specifically, it is to experiment whether the win-win

cooperation can be achieved in a learning process through a series of exercise of collaborative

teamwork conducted in the classroom, in which participants (students) are encouraged to

practice win-win strategies to resolve the disputes within and between small groups.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Collaboration

Collaboration is often used interchangeably with cooperation; although they have

different meanings: (1) collaboration is a philosophy (or style) of interaction where people are

responsible for their actions, including recognition and respect the abilities and contributions of

their peers; (2) cooperation is a structure of interaction designed to facilitate the accomplishment

of a specific goal through people working together in groups (Brody 1995). In this paper, we do

not distinguish the two terms, but look at behaviors associated with them. Cooperation can result

from coercive and voluntary forces. In the context of complex projects, coercive forces from

hierarchical authority or contractual terms often fail to reduce opportunistic behavior and ensure

cooperation (Henisz, Levitt, and Scott 2012). Instead, relational contracting based on trust

emanated from norms of obligation and reciprocity often motivates individuals to engage in

cooperative actions with others and reduces the fear regarding other parties may behave

opportunistically (Bradach and Eccles 1989).

2.2 Trust building and collaboration

For projects that comprise multiple organizations, works are mostly one-off customized

cases involving complicated interdependencies between tasks and processes across

organizational boundaries. However, the temporary and dynamic nature of project may hinder

collaboration, unless participants are able to actively cultivate cooperative relationship by trust

building across boundaries (Meyerson et al. 1996).

After stumbling for over decades, the construction industry has learned that long and

inefficient administrative and legal procedures can easily direct the issues away from their

engineering and technical essences and lead to an adversary game and competition. Lau and

Rowlinson’s (2009) study of trust in the construction industry indicates that interpersonal trust is

3

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

more sensible to demonstrate keeping commitments and performing cooperation. Their findings

point out that a good interpersonal relationship involving trust and confidence in others is a must

not only for a socially safe working place but for a profitable business partnership.

In a trustworthy relationship one may transform fuzzy uncertainty in front (the worry of

the other side’s unforeseeable behavior) into an affordable level of risk which he/she is willing or

prepared to take. By doing so, one can confidently presume the threat of opportunistic behavior

exists but is minimized (Luhmann 1979). Therefore, trust can effectively reduce the risk of

opportunism. One the other hand, risk also presents opportunities for trust building, in which

risk-taking is an important act that leads to trust, a psychological condition resulting from

repeated reciprocal interactions and risk-taking acts (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, and Camerer 1998).

Because the opportunistic tendency of human nature is challenging, some studies regards trust

building a transforming process for enhancing the quality of dyadic relationship (Duck 1990;

Zolin 2005). In this study, some particular behaviors are identified as trust building attempts; for

instance, risk-taking act, attitude to openly disclosure information, and predictable response are

actions that embody collaboration intentions.

2.3 Conflict Management and Learning

Participants in projects often need to coordinate complex tasks and processes that have a

high level of reciprocal interdependence and require mutual adjustments (Thompson 1967),

which greatly increases the risk of conflict that threatens cooperation. In addition, due to various

interests of project participants, goal incongruence is a major source of conflicts that greatly

impacts the project outcome (Thomsen et al. 2004).

Relational conflicts can diminish the cognitive functioning of the individuals involved in

the conflicts and lead to antagonistic behaviors (Jehn 1977). As a consequence, tensions in

relationship interfere with task-related collaboration, and peoples’ attention would be directed to

struggling for power rather than to working together towards completing tasks. To constructively

manage those tensions and conflicts, learning is necessary for changing the antagonistic situation

in order to keep the whole team well functioning (Luthans et al. 1995). Conflict management

involves a interactive learning process for the individuals involved to find out what are the

causes of conflicts (i.e., diagnosis) and then to search for acceptable solutions putting into

actions (i.e., intervention).

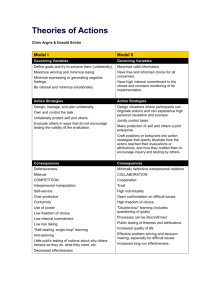

Rahim (1988) employs Argyris and Schön’s learning theory (1996) to argue that people’s

habit of defensive reasoning is the main obstacle to the learning for constructive conflict

management. This type of reasoning takes place when people fail to take responsibility for their

decisions and attempt to protect themselves against the negative consequences of the decisions

by blaming others. This psychological reaction leads everyone into adversary interactions that

are totally opposite to those for trust building. As a result, the defensive reasoning would highly

likely result in the situation that individuals, groups, intergroups, and the whole project team stop

learning and are unable to diagnose and intervene existing or potential conflicts.

On the contrary, constructive conflict management involves attitudes and actions of

taking responsibility, open discussion, and actively improving the status quo. All these behaviors

are essential for learning under interpersonal interaction. In this study, we aim to identify the

effects of learning on collaboration in a setting game, in which the consistency of the overall

activities is well retained. The effects of learning are measured based on Argyris and Schön’s

theory. In the following, we first describe the fundamental of learning for win-win cooperation

and then the method employed.

4

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

3. FUNDAMENTAL OF LEARNING FOR WIN-WIN COOPERATION

The presence of conflict is essential for learning in an organization (Luthans et al. 1995),

and in the need for constructively managing conflict lies the potential for collective learning

(Pascalc 1990; Senge et al. 1994). Argyris and Schön (1996) define learning as the path of error

detection and correction and categorize learning into two types. First, single-loop learning refers

to cases in which errors corrected without altering the underlying paradigm (i.e., interpretive

frames). Second, double-loop learning refers to cases in which errors corrected by changing the

paradigm and then the actions. In other words, single-loop learning results in changes of

people’s perceptions and behaviors within an existing interpretive frame, and double-loop

learning involves cognitive and behavioral changes that entail a change in the existing

interpretive frame.

Rahim and Bonoma (1979) argue that good strategies of managing conflict can encourage

double-loop learning and advocate that organizations should move beyond exercising single-loop

learning for troubleshooting to foster double-loop learning with constructive conflict

management. In addition, learning that shape the motivations of individuals in conflicts also

affect their responses to the conflicts. Learning for cooperation is fundamentally about

individuals or/and teams working together to foster the “shared interests” (Daniels and Walker

2001: 57). The process that directs individuals’ focus shifting from self-interests and individual

gains to the shared interests and mutually beneficial outcomes changes their motivations in the

team work.

Based on these lines of research, we see that cooperation is a structure of people’s

interaction to accomplish a specific goal, in which win-win strategies are embedded in a trustbuilding process. We presume that the process that enacts double loop-learning for win-win

cooperation is constructive conflict management other than resolution, in which conflict is not

necessarily to be avoided, reduced, or terminated. Instead, it is an important ingredient to

facilitate double loop learning that exploits the constructive functions of conflict and fosters the

trust in people’s interaction.

4. RESEARCH METHOD AND EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

We conducted an exploratory experiment to study the potential effect of learning on

collaboration. An undergraduate course in civil engineering, Engineering Negotiation, was

adopted for students to learn how to practice win-win cooperation in a specially-designed

program comprising three games of conflict management. In total, thirty-two juniors and seniors,

ages ranging from 21 - 23, participated. Some of them had construction or design related intern

experience, but less than six months. Another thirty-two students of business major who had

never taken courses from the first author, and whose department had no similar courses, joined

the experiment in the third game as the control group for two types of learning.

4.1 Underlying Assumptions of the Program Design

The processes of the program are designed to bridge and transfer what is learned by

individual team members to the collective and vise versa. We assume that individual learning is a

necessary condition for collective team learning in the intra- or/and the inter-team interactions

(negotiations). The team as a collective can learn from its individual members through a certain

mechanism (Argyris 1978). The unique mechanism developed in each team enables its members

to collectively engage in the exercises involving diagnosis of problems and intervention in

5

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

conflicts. Through this process, team members who see different aspects of a problem can

explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond the limited options that they

individually perceived as possible. By doing so, they can preserve and acquire new knowledge

and inspire each other to adopt the new values and ways of interpreting things fostered in the

process.

In terms of motivation, the exercises of the program are designed for individuals to learn

how to collectively achieve a goal that they cannot achieve alone (Booher and Innes 2001). The

design requires participants to engage in activities with a high level of interdependence so that

they can learn to make choices between collective beneficial goals and self-interested goals and

learn from the consequences of their choices.

4.2 Procedure

In this program, students played three games in groups of four in three consecutive

weekly meetings. These three games represent three different simplified scenarios: (1) intragroup joint decision making to deal with the threat of a natural disaster, (2) negotiation between

two groups to deal with their inter-group competition, and (3) cooperation with a competitor

group to achieve an inter-group win-win for mutual gains.

The first game (Game 1) aims to provide a simple context for group members to interact

and to develop their patterns of joint decision-making. The second game (Game 2) allows

students to learn the negative consequence of zero-sum competition by performing a negotiation

under the given scenario of the prison’s dilemma game. The third game (Game 3) is to test

whether the students make any changes in their strategies and turn to cooperative actions for

win-win after the learning experience, by arranging them to negotiate with a new group of

students under a similar game. Goals and setting of the adopted games are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 Goals and Setting of Games

Game

1

Main Goal

To make

joint

decisions

Context

We are trapped in a severe snow storm. We have to jointly

decide how to survive the disaster. We also need to prioritize

the things that we should keep for surviving.

Measurements

After-class

summaries

2

To

maximize

the gain

Questionnaire;

After-class

summaries

3

To achieve

win-win

outcomes

We have a competitor group in the market. Our profitability

depends on matching our price with theirs in a pricing game.

This game runs many rounds, and the profit is accumulated

accordingly.

Same as above, but this time we still need to achieve the

same profitability but by turning the adversary game into a

collaborative win-win. Limit communication between both

sides to build trust is conducted by some verbal negotiations

or by the messages conveyed by our prices.

Observation

reports;

Questionnaire;

After-class

summaries

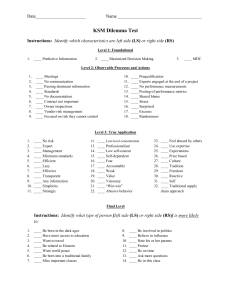

Note: We also administered questionnaires of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Keirsey

1998) and the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI; Kilmann and Thomas 1977) to

measure students’ personalities and conflict management styles and assess their effects on

cooperation. However, this part of results is not discussed in this paper.

Each of the three games lasted for three hours. The purpose of the three-stage design is to

observe two types of learning mechanisms. In each of Game 2 and 3, students played 8 times of

the same game and demonstrated the behaviors of single-loop learning. Each group gained their

6

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

experience by trial-and-error for their best winning tactics under intensive interactions. In order

to strengthen the learning leading to the double-loop learning, after-game assignments,

discussions, and three lectures are given to facilitate reflection of experience and to elaborate

useful concepts and skills for trust building and cooperation.

4.3 Measurements

The double-loop learning is examined in two sets of data: (1) the changes of students’

winning strategies from the second to the third stages, and (2) the reflection stated in their

summaries after each game. As the result, the students of business major who had never learned

the concepts from the first author’s courses could only gain trial-and-error learning from the 8

rounds of game in the third stage. This allows us to differentiate the effect of single-loop learning

and double-loop learning on collaboration. The resulting decision-making patterns and

negotiation strategies were measured with five approaches.

First, each group was assigned one observer to record group members’ interactions.

Second, immediately after the exercises, the students were asked to complete a questionnaire

about their intention and instinctual reaction (i.e. feeling and emotion, or “affective responses;”

Gilboa 1994). Third, the students were required to provide after-class reports summarizing their

reflections of the lessons learned from each exercise. Fourth, after each stage, the instructor led

group debriefing and discussion to recap the activity and clarify some ambiguous issues. Finally,

the first author interviewed four group leaders to delve into actual group interactions.

5. GAME CONTEXTS AND RESULTS

In Game 1, students jointly discussed the situation and learn about the communication

between the members of the group. After Game 1, students reported how they arranged their

attention and effort on different issues in their discussion for reaching consensus including: (1)

Proposing alternatives and reasoning them (19%), (2) Getting things done soon (16%), (3)

Figuring out rules and procedures to make decision (38%), and (4) Making a friendly climate for

discussion (28%). These four issues are correlated to the four main concerns of conflict

management (Shell 1999) that signify different tendencies and preferences of communication

approaches (Crowley 1996). Figure 1 illustrates the result.

Dominating

Collaborating

16%

19%

Compromising

38%

Avoiding

38%

28%

19%

16%

28%

Accommodating

Figuring out rules and procedures to make decision

Making a friendly climate for discussion

Proposing alternatives and reasoning them

Getting things done soon

Figure 1 Main Issues in Group Discussion for Reaching Consensus

7

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

In Game 2, the group exercise is based on a modified version of the oil pricing game

originally written by Fisher (1986). This is a multiple-round, iterative game under a scenario of

tactic collision between two groups upon the price of oil. It is about two companies selling oil to

a market that they commonly share. Each group's profitability would depend on the price they set

and the price set by the other group (as shown in Figure 2). Therefore, the profitability is closely

related to one side’s prediction of the likely actions of the other side as well as their accordingly

countermeasures. In this way, the game subtly places both sides in an iterated prisoner's

dilemma, in which each group must maneuver, in a way of limited communication, to produce

their best payoffs.

Figure 2 Price—Profit Diagram

Figure 3 Price—Market Share Change Diagram

In Game 2, the profit for each round is determined by the gained unit profit times the

market share which may vary according to the comparative prices of parties in the game (Figure

3). In addition, two criteria were used to judge the parties’ survival at the end of the game: (1)

minimum average profit > 500, and (2) minimum market share > 30%. The main goal of each

group in Game 2 was to maximize the total profit.

There is one mechanism embedded in the game that provides incentives for opportunism.

If one group choose a more competitive price than the other group and slightly sacrifice their

market share as the trade-off, this would increase their profit at the expense of the profit of the

other group. On the other hand, if the prices of both parties are the same, their market shares

remain unchanged. In other words, they can retain one half of the market share from the

beginning as long as the prices remaining equal.

To strengthen the effect of the mechanism that induces opportunism, players were

initially told that they would only play the game 4 times in order to shorten the time they

expected to maximize their own profits. In addition, before the expected end-game round

(Rounds 4 and 8), players were told that their profits would be doubled.

In most rounds, communication was through a limited way by showing a “number”

indicating their prices. At certain points, both groups are given the opportunity to communicate

explicitly by face to face negotiation. Table 2 shows an example of results.

Table 2 The Records of Game 2: Group A against Group B

Round

1

2

Group A’s Price

Market share (%)

Group B’s Price

Profit

Market share (%)

10*

50

20

500

50

150

10*

20

45

Profit

135

53

8

530

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

3

4

(×2)

5

30

48

480

48

Average

profit

480

30

960

48

960

10*

20

48

144

48

480

10*

51

8

(×2)

48

30

6

7

30

20

510

43

129

20*

30

46

92

46

920

10*

51 (> 30)

480

20

1020

38 (> 30)

(< 500)

485

228

(< 500)

Note: (1) The game was first described as a 4-round game. After the fourth round, the

instructor announced that the game would continue another 4 rounds. (2) Each

time before the end-game round (Rounds 4 and 8), both parties were told that

their profits would be doubled. (3) There were 4 chances of face-to-face

negotiation after their trials of Round 2, 3, 5, and 7. (4) * indicates the “winner.”

Game 2 is a so-called “social trap” exercise. In any negotiation each party need to make

decisions regarding (1) reaching pricing agreement or not, and (2) subsequently, honoring that

agreement or not. Once the game was repeated a number of times (as shown in table 2), both

groups attempted to tacitly achieve a better payoff in the short round either by anticipating the

other party to defect the agreement or by cunningly defecting the agreement at certain trials. As

shown in Table 2, when the end-games were expected (Rounds 4 and 8), the groups would tend

to competed by maximizing short-term gains.

According to the after-game debriefing and students’ summaries, the most efforts of all

groups were put on trying to beat their competing groups. Therefore, assuming the other side an

opportunist reflected their dominant interpretive frames of self-defense. Distrusting was reflected

in the actions of competition that strove to safeguard and/or increase their own profitability. The

chances of face-to-face negotiations mostly aimed at probing the other group’s intentions, and

less at making concessions. Playing along with the game, both groups carefully adjusted pricing

strategies according to what they had learned. They focus on making anticipation and modifying

(or trial and error) the expectation in the game just like a thermostat that responses to high or low

temperatures by turning the heat on and off. This is typical single-loop learning.

Several students reported in their summaries (one week later) that their group learning

seems to differ from their individual learning. They pointed out that their groups’ strategies and

decisions failed to reflect what they learned individually. Some even complained that their

personal input had little impact on the group behavior, indicating group think effect at work

(Janis 1972). For example, some individuals were aware that long-term maximization required

mutual trust to survive the doomed social trap, however significant short-term gains still attracted

their group to break the agreement.

9

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

Some students argued that the goal to maximize the total profit was ambiguous and was

easily misinterpreted. Their response tended to be driven by the anticipation of possible negative

and adversarial intentions of the other party. Consequently, such projections became selffulfilling by leading to competition and adversary acts.

In Game 3, the experienced students who participated in the entire program played the

game with new-comer groups, in which the experienced group must decide whether to adopt a

cooperative stance or a competitive strategy. Once again, they must maneuver and negotiate in a

similar environment of limited communication, to maximize individual and joint gains. Table 3

shows one of Game 3 records.

Table 3 A Game 3 Records of Group A against New Group B

Round

1

2

3

4

(×2)

5

Group A’s Price

Market share (%)

Profit

50

Average

profit

50

250

20*

30

40

80

57

1140

20*

30

45

90

49

1500

41

980

30*

50

10

410

20*

30

40

80

48

960

30*

10

675

40

200

30

35

30

350

47

470

30

35 (> 30)

528

Profit

10

750

45

8

(×2)

Market share (%)

30*

6

7

New Group B’s Price

30

700

47 (>30)

(> 500)

625

840

(> 500)

Note: (1) * indicates the “winner.”

After Game 3, the debriefing of the results allowed students to examine the different

outcomes between Games 2 and 3. They could also reflect on both what they had learned from

these two games that produced their behavioral difference. All the lessons learned and reflections

were discussed openly, and the instructor (the first author) highlighted the commonalities and

differences of their findings and made connections with key concepts and theories related to

cooperation.

The discussion and students’ summaries showed that students experienced a different

way interpreting the action of their paired group. In Game 3, they could better sense how the

other team (or themselves earlier) would make imprecise assumptions once being involved in the

competition of conflicting interests, so that they became aware of keeping their own assumptions

10

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

explicit and testing them in the game. Moreover, their follow-up reflection stated in the

summaries was valuable for making sense of why the outcomes of Game 3 differed from Game

2. Most students reported in their summaries that they were impressed by the experienced of

altering their actions to reach the desired solution in trust. The way they learned to build trust

with others was quite straightforward by being predictable of what they did and being consistent

with what they said (shown in Table 3). Subsequently, several students were very pleased that

the decision making towards trust was much easier and faster. The after-game questionnaires

recording their decision making time confirmed this point.

The three games demonstrated that learning for win-win cooperation did not easily occur

by just knowing the importance of cooperation. It requires experiences in real practices.

Theories of learning suggest that double-loop learning involves a process of confronting the

existing interpretive frames regarding how and why certain things happen, breaking them down,

and acquiring a new model or set of cause-effects interpretations to replace the old ones.

Nevertheless, Argyris and Schön (1974) point out:

The trouble people have in learning new theories may stem not so much from the

inherent difficulty of the new theories as from the existing theories people have

that already determine practices. We call their operational theories of action

theories-in-use to distinguish them from the espoused theories that are used to

describe and justify behavior. We wondered whether the difficulty in learning

new theories of action is related to a disposition to protect the old theory-in-use.

This explains why learning does not simply occur by knowing new theories. Existing

interpretive frames tend to persist and lead to experiences and justifications that reinforce the

interpretive frames. The process of learning from reflection of experience is crucial because it

makes people aware of discrepancies between knowing and experience (Marsick, Sauquet, and

Yorks 2006), which allows new interpretive frames to be adopted. This meta-examination of

underlying assumptions is double-loop learning. It stands in contrast to single-loop learning, in

which people adjust tactics when actions do not produce intended results.

6. DISCUSSIONS

Learning can be described as a process whereby people’s interpretive frames are

internalized into their cognition thus leading to changes of thoughts and actions (Dewey 1938;

Kolb 1984). Learning by doing (or exercising) implies that there is an experience (i.e. the doing)

that causes such changes. This paper presents a case of learning by doing for win-win

cooperation addressing primarily how learns (students) learn. Employing the difficult prison’s

dilemma game as a metaphor, the students experienced two types of learning through exercising

the same situation twice. By comparing their different behaviors in two games through

reflection, student witnessed their changes of thoughts and actions in a learning process. The

preliminary results indicate that:

1. The results showed the positive outcomes of group learning through the experiment.

Nevertheless, the students’ learning as a member of a team seems to differ from their

individual learning. Many of the reflection reports of students showed that their group

negotiation strategies failed to reflect what they had learned individually. Some group leaders

complained that they learned significantly by being in the leadership position, but their

personal input had little impact on the group behavior as a whole.

2. The single-loop learning is repeated a number of times in the prisoner’s dilemma game, and

11

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

most teams become more sophisticated in terms of their rational reasoning through their

experiences. In fact, most teams hardly achieved what they desired since the development of

operational trust was easily broken by fear of the breach of the agreements that the leaders

reached in the negotiations between rounds, especially when an end-game was anticipated.

3. The double-loop learning was driven by needs for getting out of the paradoxical trap to

achieve mutual gains. By understanding the common human fears of distrust, some

experienced teams became more able to empathize with the feelings of their opponents and

were much willing to continue the efforts of trust building in the game. Because of their

empathy with others, coupled with their rational reasoning and the knowledge learned from

the lectures, the win-win cooperation became a feasible goal for them.

The measurements of MBTI for personality and the TKI measurements for conflict

management style are very likely to be correlated with each other. Nevertheless, additional

analysis efforts are needed to explore their links in between. Our current accomplishment is not

sufficient to further discuss in this paper yet. Preliminary findings drawn out in the present study

are to elicit future cross-national collaborations on similar researches.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We also

thank the financial support from the National Science Council project number NSC 99-2211-E006-189-MY3.

REFERENCES

Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1974) Theory in Practice. Increasing professional effectiveness, San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass, CA, USA.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. (1978) Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective,

Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass, USA.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. (1996) Organizational learning—II, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley,

USA.

Booher, D.E., and Innes, J.E. (2002) “Network Power in Collaborative Planning”, Journal of

Planning Education and Research, 21(3), 221-236.

Bradach, J. L., and Eccles, R. G. (1989) “Price, Authority, and Trust: From Ideal Types to Plural

Forms”. Annual Review of Sociology, 15, 97-118.

Brody, C.M., (1995) “Collaboration or cooperative learning? Complimentary practices for

instructional reform”, The Journal of Staff, Program & Organizational Development 12(3),

133-143.

Ceric, A. (2011) “Minimizing communication risk in construction”. In T. M. Toole (Ed.),

Engineering Project Organizations Conference. Estes Park, Colorado.

Crowley, L.G. (1996) “Engineering sales: Process of understanding.” The ASCE Journal of

Management in Engineering, 12(2), 40-43.

Duck, S. (1990). Understanding Relationships, Guilford Press, New York.

Dutton, J. E., and Jackson, S. E. (1987) “Categorizing Strategic Issues: Links to Organizational

Action”. The Academy of Management Review, 12(1): 76-90.

Gulati, R. (1995) “Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for

Contractual Choice in Alliances”. The Academy of Management Journal, 38(1): 85-112.

Daniels, S.E. and Walker, G.B. (2001) Working through environmental conflict: The

Collaborative Learning Approach, Westport CT: Praeger Publishers.

12

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

Dewey, J. (1938) Experience and Education. New York: Macmillian.

Gilboa, E. (1994) “Personality and the Structure of affective Responses”. Chapter 5 of Emotions:

Essays on emotion theory, Stephanie H. M. van Goozen; Nanne E. van de Poll; Joseph A

Sergeant (Eds.), 135–160, Lawrence Eribaum Associates, Inc., Hillsdale, NJ, USA.

Henisz, W. J., Levitt, R. E., and Scott, W. R. (2012) “Toward a unified theory of project

governance: economic, sociological and psychological supports for relational contracting”.

Engineering Project Organization Journal, 2(1-2): 37-55.

Fisher R. (1986) Oil Pricing Exercise, the Clearinghouse, Program on Negotiation, Harvard Law

School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Fligstein, N., and McAdam, D. (2011) “Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields”.

Sociological Theory, 29(1): 1-26.

Gulati, R. (1995) "Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for

Contractual Choice in Alliances". The Academy of Management Journal, 38(1): 85-112.

Janis, I.L. (1972) Victims of groupthink: a psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and

fiascoes. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-14002-1.

Jehn, K.A. (1997) “A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions of organizational

groups”, Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 530-557.

Keirsey, D. (1998) Please Understand Me II: Temperament Character Intelligence, Prometheus

Nemesis Book Company, Del Mar, CA. USA.

Kilmann, R. H., and Thomas, K. W. (1977) “Developing a forced-choice measure of conflict-handling

behavior: The ‘Mode’ instrument.” Educ. Psychol. Meas., 37, 309–325.

Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential Learning; Experience as the Source of Learning and Development.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Luthans, F., Rubach, M.J., and Marsnik, P. (1995) “Going Beyond total quality: The

Characteristics, techniques, and measures of learning organizations”, International Journal of

Organizational Analysis, 3, 24-44.

March, J.G. and Simon, H.A. (1993) Organizations, 2nd ed., Cambaidge: Blackwell Publishers.

Marsick, V. J., Sauquet, A., and Yorks, L. (2006) “Learning through reflection”. In M. Deutsch,

P. Coleman, & E. Marcus (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution (2nd ed., pp.486-506).

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McGregor, D. (1960) The Human Side of Enterprise, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Pascale, R.T. (1990) Managing on the Edge: How the smartest companies use conflict to stay

ahead. NY: Simon and Schuler, U.S.A.

Poundstone, W. (1992) Prisoner's dilemma, Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., New York,

NY, USA.

Rahim, M. A., and Bonoma, T. V. (1979) “Managing organizational conflict: A model for

diagnosis and intervention.” Psychological reports, 44, 1323–1344.

Rahman, M. M., and Kumaraswamy, M. M. (2002) “Joint risk management through

transactionally efficient relational contracting”. Construction Management & Economics,

20(1): 45-54.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., and Camerer, C. (1998) “Introduction to Special

Topic Forum: Not so Different after All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust”. The Academy of

Management Review, 23(3): 393-404.

Senge, P.M., Kleiner, A., Roberts,C., Ross, R.B., and Smith, B.J. (1994) The fifth discipline

fieldbook, NY: Doubleday, U.S.A.

Shell, G.R. (1999) Bargaining for Advantage: Negotiation Strategies for Reasonable People,

Penguin Books, Penguin Putnam Inc., New York, NY, U.S.A.

13

Proceedings – EPOC 2012 Conference

Summers, R.J. and Cronshaw, S.F. (1988) “A study of McGregor’s Theory X, Theory Y and the

influence of Theory X, Theory Y Assumptions on Causal Attributions for Instances of Work

Poor Performance.” in McShane, S.L. (Ed.), Organizational Behavior, ASAC 1988

Conference Proceedings, 9(5). Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 115-123.

Thompson, J.D. (1967) Organization in Action. New York.

Thomsen, J., Levitt, R.E. and Nass, C.I. (2004) “The Virtual Team Alliance (VTA): Extending

Galbraith’s Information-Processing Model to Account for Goal Incongruency.”

Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory, 10, 349–372.

Tsai, J.S., and Chi, C.S.F. (2009) “Influences of Chinese cultural orientations and conflict

management styles on construction dispute resolving strategies.” ASCE Journal of

Construction Engineering and Management, 135(10), 955-964.

Tsai, J.S., and Chi, C.S.F. (2011) “Linking Societal Cultures, Organizational Cultures and

Conflict Management Styles” Engineering Project Organizations Conference, Aug. 9-11,

Estes Park, CO, USA.

Uzzi, B. (1997) “Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of

Embeddedness”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(1): 35-67.

14