The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania

advertisement

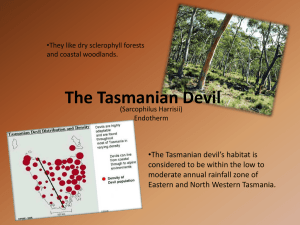

The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania The Hunter takes place on Tasmania’s Central Plateau, where “One hundred and sixty-five million years ago potent forces had exploded, clashed, pushed the plateau hundreds of metres into the sky.” [a, 14] The story is about the hunt for the last Tasmanian tiger, described in the novel as: Fig 1. Paperbark woodlands and button grass plains near Derwent Bridge, Central Tasmania. Source: J. Stadler, 2010. “that monster whose fabulous jaw gapes 120 degrees, the carnivorous marsupial which had so confused the early explorers — a ‘striped wolf’, ‘marsupial wolf.’” [a, 16] Biodiversity “Biodiversity”, or biological diversity, refers to variety in all forms of life—all plants and animals, their genes, and the ecosystems they live in. [b] It is important because all living things are connected with each other. For example, humans depend on living things in the environment for clean air to breathe, food to eat, and clean water to drink. Biodiversity is one of the underlying themes in The Hunter, a Tasmanian film directed by David Nettheim in 2011 and based on Julia Leigh’s 1999 novel about the hunt for the last Tasmanian Tiger. The film and the novel showcase problems that arise from loss of species, loss of habitat, and contested ideas about land use. The story is set in the Central Plateau Conservation Area and much of the film is shot just south of that area near Derwent Bridge and in the Florentine Valley. In Tasmania, land clearing is widely considered to be the biggest threat to biodiversity [c, d]. Land clearing is performed to make room for [d]: • • • • • pasture for livestock land for cropping plantations, or tree farms for growing soft and hard wood dams cities and towns These activities are important for Tasmania’s economy. For example, in 1999, the year that The Hunter was written, Tasmania produced [e]: • 70% of Australia's decorative veneers • 50% of Australian produced printing and writing paper • 57% of Australian newspaper. Land clearing is controversial because it: • destroys native vegetation and forests containing centuries-old trees—such as myrtle, sassafras, leatherwood and celery-top pine [f] • destroys habitat for native birds and wildlife that die, as a result, from exposure, starvation, and stress [g] • causes water that was once used by plants to rise through the soil bringing salt deposits with it. The salt water makes the soil less productive for farming, and taints river and water supplies. Damage from salt water also has the potential to affect foundations, parks, gardens, roads, and buildings in towns and cities. [g] • emits greenhouse gases into the atmosphere through bulldozing, and rotting and burning bush [g] 1 Fig 2. A banner protesting deforestation. Source: Florentine Protection Society, photograph by Alan Lesheim. The Hunter dramatises heated debates about forest management and logging in an economically and ecologically vulnerable region of Tasmania and the film includes images of an actual forest blockade with protesters’ banners stating “Save the Upper Florentine.” Biodiversity and the thylacine The Hunter features one of the most famous extinct species in the world—the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine. The world’s last thylacine was captured and sold to Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo in 1933, and died on 7 September 1936. It was also added to the list of protected wildlife in 1936 and declared extinct by international standards in 1986. It is the only mammal to have become extinct in Tasmania since European settlement. [h] The thylacine looked like large, long, yellow or greyish dog with stripes and a big head. It had short ears, short fur, and a stiff tail. Its scientific name, Thylacinus cynocephalus, means “pouched dog with a wolf’s head”. [h, i] Contrary to any of its names, it was not a tiger, dog or wolf, but a marsupial. Although known as the “Tasmanian” tiger, thylacines once lived throughout mainland Australia and New Guinea. It is believed that both the Tasmanian tiger, and the Tasmanian devil, became isolated on Tasmania after a land bridge to mainland Australia was flooded at least 10,000 years ago. [j] Tasmanian tigers ranged from Kakadu and the Pilbara down to Tasmania (as evident in Aboriginal rock art), but their range later shrunk to the Tasmanian highlands. Thylacine facts: • A fully-grown Tasmanian tiger was about 160-180cm long from head to tail, and weighed 30kg. [h, j] Fig 3. Thylacines, 1906. Source: Smithsonian Institution Archives. • It wasn’t really a tiger, but people thought it looked like one because it had 13-20 stripes from the base of its tail to its shoulders. [h] • The oldest thylacine bones found in Australia came from Riversleigh World Heritage fossil site in north-west Queensland, and are 30 million years old. At least seven different species have been found at this site—from the size of a small cat, to the size of a fox. [i] • The thylacine ate only meat, and was the world’s largest meat-eating marsupial. [h] The largest meat-eating marsupial is now the Tasmanian devil. • It had an unusually large jaw, which it could open very wide. Despite this, its main source of food was likely wallabies, or other small animals like possums, and birds. [j, n] Recent research has shown that it was likely too weak to kill sheep, as it was once accused of doing. [l] • It had 46 teeth [i]—4 more than an adult dog and 14 more than an adult human. • Both male and female thylacines had pouches—females had a backward facing pouch for carrying young, while males had a pouch to protect their reproductive organs. [i] • Thylacine pups were probably born in litters of 3 or 4, and had a gestation period of one month, followed by another 3-4 months in their mother’s pouch. [n] • Thylacines lived up to 9 years in captivity, but they probably only lived 5-7 years in the wild. [n] 2 Reasons for thylacine extinction: • Many scientists believe that the thylacine became extinct on mainland Australia because of dingoes. According to the “niche overlap hypothesis,” the thylacine and dingo had similar hunting techniques and therefore competed for the same food. Recently, scientists found that unlike the dingo, with its locked elbows designed for outrunning its prey, thylacines had flexible elbows suggesting that they ambushed their prey. [o] The reasons given for the extinction of the thylacine in The Hunter are: “a combination of habitat fragmentation, competition with wild dogs, disease, and intensive hunting had forced their demise.” [a, 37] • Tasmanian tigers, like Tasmanian devils, are known to have poor ‘genetic diversity’ [k], which is thought to be due to their separation from mainland Australia. [p] Being related genetically makes them prone to effects of inbreeding such as disease, reduced fertility, lower birth rates, higher infant mortality, and general inability to adapt to changes in their environment. • Using models that simulate the effects of bounty hunting, habitat and loss of prey, scientists have shown that it was ultimately humans that were the cause of the thylacine’s demise. [m] Thylacines were thought to be killing livestock, especially sheep, in an environment where wool was quickly replacing whaling and sealing as Australia’s main export. [q] In 1830, Van Diemen’s Land Co. introduced thylacine bounties. From 1888-1909 the Tasmanian government paid for 2,184 bounties. By 1910, thylacines were considered rare and sought by zoos around the world. [n] Cloning/bioethics and the Tasmanian tiger In the film The Hunter, the Tasmanian tiger is hunted because it is believed to have toxic venom in its bite that can paralyse its prey. The notion that the Tasmanian tiger had a venomous bite is entirely fictional, and there is no evidence to support this. On the other hand, Tasmania is home to the Tasmanian Tiger snake, which is known for producing large amounts of highly toxic venom. [t] Martin David’s job in the film is to kill the Tasmanian tiger so that he can get a sample of its DNA to recreate the fictitious biotoxin. In reality, he probably wouldn’t need to kill the Tasmanian tiger to get a sample of its DNA. Scientists have already cloned other animals from blood [aa] and skin [z] samples. If the thylacine was captured alive, the genetic information needed to identify the toxin gene could come from a blood, skin, or possibly hair [bb, cc] sample (with follicles). The Hunter also contains speculation about cloning the thylacine to develop biological weapons: “By studying one hair from a museum’s stuffed pup, the developers of biological weapons were able to model a genetic picture of the thylacine, a picture so beautiful, so heavenly, that it was declared capable of winning a thousand wars. Whether it will be a virus or an antidote, M does not know, cannot know and does not want to know, but there is no question the race is on to harvest the beast. Hair, blood, ovary, foetus — each one more potent.” [a, 40] Cloning the thylacine was once an active program of the Australian Museum but it was unsuccessful. The “Thylacine Cloning Project” relied on using cells taken from a thylacine pup that have been preserved for more than 100 years. [v] When an animal dies so do its cells and the DNA inside them, and so this makes it difficult for scientists to get all the information they need for cloning using preserved thylacines. [u] Cloning of the Tasmanian tiger is controversial because [w]: • Some people think that we should be focusing our money and efforts on protecting the animals we have, including endangered species, and preserving their habitat instead. • Some people believe that cloning a species sends the wrong message about extinct animals (that they can be brought back to life). • It is also unclear whether a recreated Tasmanian tiger could survive in what is left of its remaining habitat, or what effect it would have on that habitat. It is likely that any successful Tasmanian tiger clone would have to live in captivity. Fig 4. A preserved Thylacine pup (Thylacinus cynocephalus). Source: Museum Victoria If researchers succeed in cloning the Tasmanian tiger, the Tasmanian devil is thought to make a good surrogate mother for the embryo. See http://www.biotechnologyonline.gov.au/popups/int_thylacinecloning.html for an interactive demonstration of the potential thylacine cloning process. 3 Martin sets traps to snare the elusive thylacine, but he attracts only wallabies, Tasmanian devils and a spotted tiger quoll: Biodiversity and the Tasmanian devil In The Hunter, Martin David poses as a Tasmanian devil researcher. Tasmanian devils are the thylacine’s closest genetic relative, along with the numbat. “The track they are on was cut by old trappers. In his study of the area he’d read that a hundred years ago the same ground would have been regularly used by men carrying up to seventy pounds of wallaby and possum pelts across their shoulders. Tiger pelts, too, or carcasses: once upon a time. Up on the plateau more tigers were caught than anywhere else on the island.” [a, 15] Fig 4. Tasmanian Devil. Source: Gerry Pearce, Australian-wildlife.com The Tasmanian devil is about the size of a small dog. It is mostly black with the odd white patch on its chest, shoulder or rump. It has a stocky frame with longer front legs than back. They can weigh up to 13kg. [r, s] Its scientific name, Sarcophilus harrisii, means “Harris’s meat lover”—it was George Harris who wrote the first published description of the Tasmanian devil in 1807. Tasmanian devils are susceptible to Devil Facial Tumour disease, which is a contagious cancer that spreads like an infection and is always fatal. The cancer hides from the Tasmanian devil immune system so it does not recognise the cancerous cells as foreign and reject them. [x, y] So far, the disease has killed 84% of the Tasmanian Devil population and they are currently listed as an endangered species. [r, x] In an effort to start a cancer-free refuge of wild Tasmanian devils, a group of 15 of them was introduced in 2013 to Maria Island, off the east coast of Tasmania. [x] Tasmanian devil facts: • The Tasmanian devil was likely given its name because of its spinechilling screeches and black colour. [s] • Since extinction of the thylacine, Tasmanian devils are now the largest carnivorous marsupial in the world. [s] Fig 5. Tasmanian Devil Species Occurrence Map. Source: Atlas of Living Australia, http://bie.ala.org.au/species/ Sarcophilus+harrisii The Hunter invites us to think about biodiversity issues including loss of habitat, extinction, land use values, and the possibilities that scientific advances in genetic engineering and biological warfare might bring in the future. 4 References for The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania [a] Julia Leigh (1999). The Hunter. Penguin: Ringwood, Vic. [b] State of the Environment, Tasmania (2006), “Introduction”, http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/bio/4/ index.php [c] State of the Environment, Tasmania (2006), “Land Clearance - At a Glance”, http:// soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/bio/4/issue/41/ataglance.php [d] State of the Environment, Tasmania (2005), “Land Clearing in Tasmania”, http://www.wwf.org.au/ news_resources/archives/landclearing/landclearing_in_tasmania/ [e] State of the Environment, Tasmania (2006), “Native Forests - At a Glance”, http:// soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/bio/4/issue/58/ataglance.php [f] Richard Flanagan (2007), “Out of Control: The Tragedy of Tasmania’s Forests”, The Monthly, http:// www.themonthly.com.au/monthly-essays-richard-flanagan-out-control-tragedy-tasmania-s-forests-512 [g] Bush Heritage (2013), “Land Clearing and its Impacts”, http://www.bushheritage.org.au/ natural_world/natural_world_land_clearing Other links for The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania Video of the last Tasmanian tiger: http:// www.youtube.com/watch? v=6vqCCI1ZF7o Threatened species are now protected under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act): http://www.environment.gov.au/ resource/epbc-act-frequently-askedquestions The Thylacine Museum: A Natural History of the Tasmanian Tiger: http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/ [h] Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania (2013), “Tasmanian Tiger”, http://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/wildlife-management/animals-of-tasmania/mammals/carnivorousmarsupials-and-bandicoots/tasmanian-tiger [i] Australian Museum (2013), “The Thylacine”, http://australianmuseum.net.au/The-Thylacine/ [j] Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013), Thylacinus Cynocephalus — Thylacine, http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/ sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=342 [k] Brandon Menzies, Marilyn Renfree, Thomas Heider, Frieder Mayer, Thomas B. Hildebrandt, and Andrew J. Pask (2012), “Limited Genetic Diversity Preceded Extinction of the Tasmanian Tiger”, PLoS ONE 7(4): e35433. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035433 http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi %2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0035433 [l] M.R.G. Attard, U. Chamoli, T.L. Ferrara, T.L. Rogers and S. Wroe (2011), “Skull Mechanics and Implications for Feeding Behaviour in a Large Marsupial Carnivore Guild: The Thylacine, Tasmanian Devil and Spotted-tailed Quoll”. Journal of Zoology, 31 August 2011 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1469-7998.2011.00844.x [m] TA Prowse, CN Johnson, RC Lacy, CJ Bradshaw, JP Pollak, JM Watts, BW Brook (2013), “No Need for Disease: Testing Extinction Hypotheses for the Thylacine using Multi-species Metamodels”, Journal of Animal Ecology, Vol. 82, pp. 355–364. [n] Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service (n.d.), “Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus”, http://www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=4765 [o] Borja Figueirido and Christine M. Janis (2011), “The Predatory Behaviour of the Thylacine: Tasmanian Tiger or Marsupial Wolf?”, Biology Letters, Vol 7, pp. 937–940. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0364 [p] The University of Melbourne (2012), “Limited Genetic Diversity of the Tasmanian Tiger Sheds Light on Species’ Geographic Isolation”, http://newsroom.melbourne.edu/news/n-794 [q] Woolproducers Australia (n.d.), “About Wool”, http://www.woolproducers.com.au/about/trade/aboutwool/ [r] Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013), “Sarcophilus Harrisii — Tasmanian Devil”, http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/ sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=299 [s] Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (2010), “Tasmanian Devil” fact sheet, http:// www.parks.tas.gov.au/file.aspx?id=6477 [t] Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (2008), “Tiger Snake”, http://www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx? base=4750# [u] Museum Victoria (n.d.), “Cloning the Thylacine: Fact or Fantasy?”, http://museumvictoria.com.au/ scidiscovery/dna/cloning.asp [v] Judy Skatsoon (2005), “Thylacine Cloning Project Dumped”, ABCScience, http://www.abc.net.au/ science/articles/2005/02/15/1302459.htm [w] Inter Press Service (2002), “The Tasmanian Tiger’s Controversial Comeback”, http:// www.ipsnews.net/2002/05/environment-the-tasmanian-tigers-controversial-comeback/ [x] Carl Zimmer (2013), “Raising Devils in Seclusion”, The New York TImes, http://www.nytimes.com/ 2013/01/22/science/saving-tasmanian-devils-from-extinction.html? pagewanted=2&nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20130122&pagewanted=all&_r=0 [y] Nature (2013), “Vaccine Hope for Tasmanian Devil Tumour Disease”, http://www.nature.com/news/ vaccine-hope-for-tasmanian-devil-tumour-disease-1.12576 [z] National Human Genome Research Institute (2012), “Cloning”, http://www.genome.gov/25020028 5 References for The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania [aa] Kamimura, S., Inoue, K., Ogonuki, N., Hirose, M., Oikawa, M., Yo, M., Ohara, O., Miyoshi, H. and Ogura, A. (2013), “Mouse Cloning using a Drop of Peripheral Blood”, Biology of Reproduction, doi: 10.1095/ biolreprod.113.110098m, http://www.biolreprod.org/content/early/2013/06/25/biolreprod. 113.110098.full.pdf+html [bb] livescience (2007), “Woolly Mammoth Hair Yields 'Fantastic' DNA”, http://www.livescience.com/ 9530-woolly-mammoth-hair-yields-fantastic-dna.html [cc] ScienceDaily (2008), “Woolly-Mammoth Genome Sequenced”, http://news.psu.edu/story/ 181641/2008/11/19/scientists-sequence-woolly-mammoth-genome This fact sheet and its links were last checked on 23 March 2014. 6