Species Revival: Should We Bring Back Extinct Animals?

advertisement

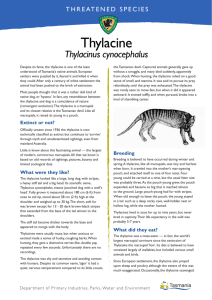

Species Revival: Should We Bring Back Extinct Animals? Scientists are debating whether to bring back vanished species. Jamie Shreeve National Geographic News Published March 5, 2013 On May 6, 1930, a Tasmanian farmer named Wilfred Batty grabbed a rifle and shot a thylacine—commonly known as a Tasmanian tiger—that was causing a commotion in his henhouse. The bullet hit the animal in the shoulder. Twenty minutes later, it was dead. A photograph taken soon afterward shows Batty kneeling beside the stiffened carcass (dead body), wearing a big floppy hat and a young man's proud grin. The Tasmanian tiger—known as a thylacine—is one of many exinct species at You can't begrudge (get angry) him some satisfaction in killing a threat to his livestock. What Batty did not know—could not know—is the center of the de-extinction debate. that he'd just made the last documented kill of a wild thylacine, anywhere, ever. In six years, the wonderfully odd striped-back creature—the largest marsupial carnivore known— would be extinct in captivity as well. The thylacine is one of 795 extinct species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List, which since 1963 has been tracking the planet's biodiversity (species count). The animals and plants on the list are organized into categories of increasing degrees of urgency, from "near threatened" through "critically endangered," until you reach the last "extinct" group, whereupon the urgency abruptly plummets (drops) to zero. An endangered species is like a very sick person: It needs help, desperately. An extinct species is like a dead person: beyond help, beyond hope. Or at least it has been, until now. For the first time, our own species—the one that has done so much to condemn those other 795 to oblivion—may be poised to bring at least some of them back. The Question of De-extinction The gathering awareness that we have arrived at this threshold prompted a group of scientists and conservationists to meet at National Geographic headquarters in Washington, D.C., last year to discuss the viability (can we do it) of the science and the maturity of the ethical argument surrounding what has come to be known as de-extinction. Next week an expanded (larger) group will reconvene at National Geographic headquarters in a public TEDx conference. People were fantasizing about reviving extinct forms of life long before Hollywood embedded the idea into our collective consciousness with Jurassic Park. Can we really do it? And if we can, why should we? The first question would seem to have a straightforward, if hardly simple, answer. Scientific developments— principally advances in cloning technologies and new methods of not only reading DNA, but writing it—make it much easier to concoct a genetic approximation of an extinct species, so long as DNA can be retrieved from a preserved specimen. (Sorry, Jurassic Park fans, the dinosaurs lived too long ago for their DNA to survive until the present.) When Is a Mammoth a Mammoth? Where things get fuzzy from this "Can we do it?" perspective is in trying to pin down what it really means to revive a species. Is a genetically engineered passenger pigeon—the prime target of one high-tech de-extinction project—the same species as the bird that flocked by the billions in North America 150 years ago? Or is it a proxy passenger pigeon, alike in every respect, but not the real deal? When does a mammoth born from an elephant qualify as the species Mammuthus primigenius? When an individual survives for more than a few minutes of life? When it grows up and is introduced to another of its kind, and they make a baby mammoth, the old-fashioned way? Or can that budding captive herd truly be considered de-extinct only when it is reintroduced to its native habitat? And just what "native habitat" are we talking about here, since mammoths haven't been around to define it for 10,000 years? On the Revival of Species Most arguments in favor of species revival fall into two basic camps: we should do it because we can do it. Why impede (stop) the progress of science, when the benefits that may accrue (build) up the road are unknown? And we should do it because we have an obligation to do it, to right some of the enormous wrong we have done by driving these cotenants of the Earth off the planet in the first place. On the other side of the debate, some conservationists argue that we should not be bringing back extinct animals when 1) We don't yet have any clear notion of how to reintroduce them into natural ecosystems; and 2) There are plenty of living species that are critically endangered. Why waste resources trying to resurrect the dead when we can use them to save the sick? Do we really need a reason to revive a vanished species? In my own experience, whether fans of de-extinction begin their justification from a scientific rationale or a moral one, they usually end by saying something like "besides, it's just such a really cool idea." It's hard to put your finger on exactly why de-extinction is so inherently exciting a concept, irrespective of any tangible benefit it may—or may not—have. Perhaps the excitement derives from the chance it affords to travel back in time and glimpse marvelous creatures from a world that no longer exists. Or maybe it's the thrill of cheating death, of reversing the ultimate irreversible. Whatever the foundation for the excitement, I am willing to bet that when a young researcher poses for a photo for the first time standing beside a revived thylacine, he or she will be wearing an ear-to-ear grin that will put Wilfred Batty's to shame. Analysis Homework Directions: Read the article above on the first page. Part One: Summarize the article on a separate sheet of paper. Use the sentence starters below to keep you organized and on track. Remember in a summary, there is no opinion. Just state the facts from the article. -The purpose of this article was …. - The first reason for this is… -The second reason for this is… -In conclusion, … Part Two: What other words could you use here? a) “that was causing a commotion in his henhouse..” Other word(s) for commotion: _________________ b) “Next week an expanded group will reconvene at National Geographic headquarters in a public TEDx conference.” Other word(s) for reconvene: _________________ c) “..so long as DNA can be retrieved from a preserved specimen.” Other word(s) for preserved: ________________ Part Three: Answer using complete sentences please. 1) Based upon the article, what is the process that scientific claims must take before being accepted by all scientists of the world? Explain. 2) Do you think we should revive extinct species? Why/why not? Explain with evidence please. df3) How do humans cause the extinction of organisms (animals or plants)? Describe at least two ways.