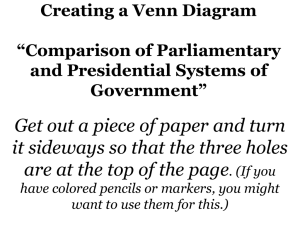

comparison of appointment and dismissal powers of the executive

advertisement