Children's Workforce Strategy

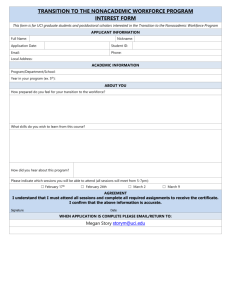

advertisement