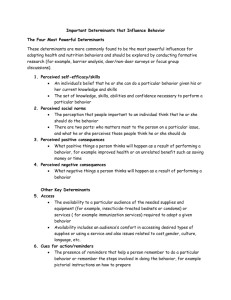

Perceived Perspective Taking: When Others

advertisement