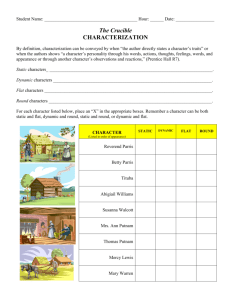

The Crucible - Arthur Miller

advertisement