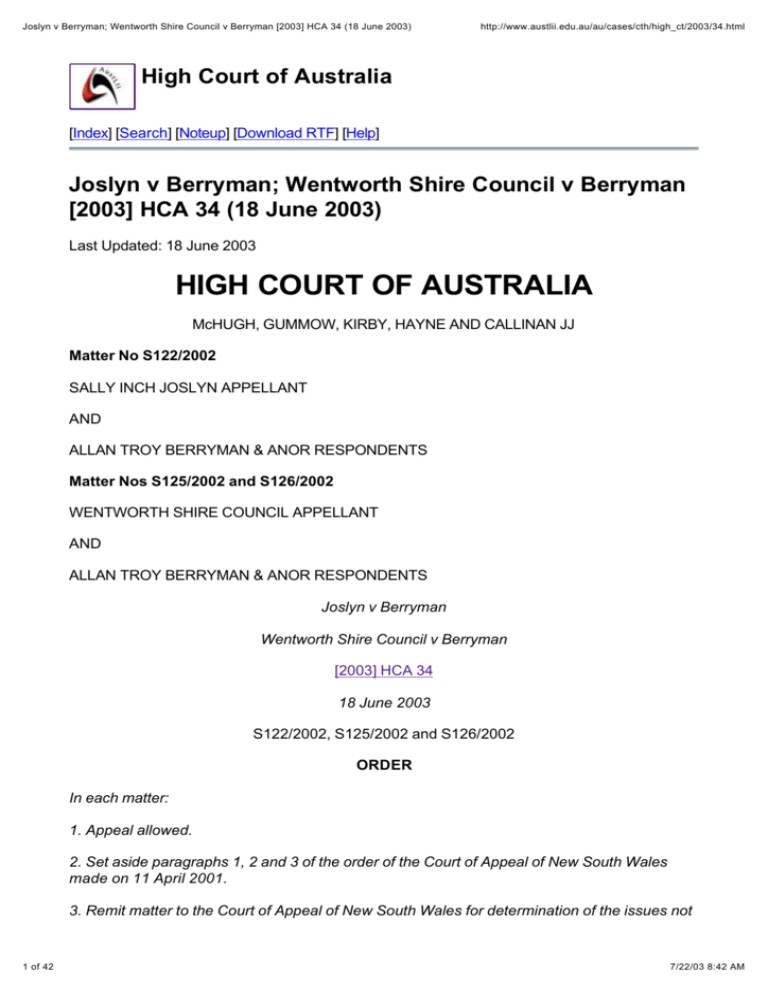

Joslyn v Berryman

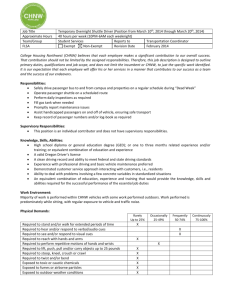

advertisement