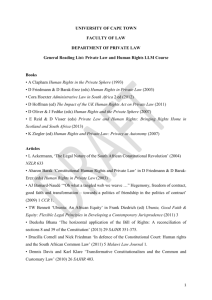

the development of the common law under the constitution

advertisement