An Overview of

Philippine

Fisheries

PORFIRIO M. ALIÑO

The Marine Science Institute

University of the Philippines

Diliman 1101 Quezon City

PHILIPPINES

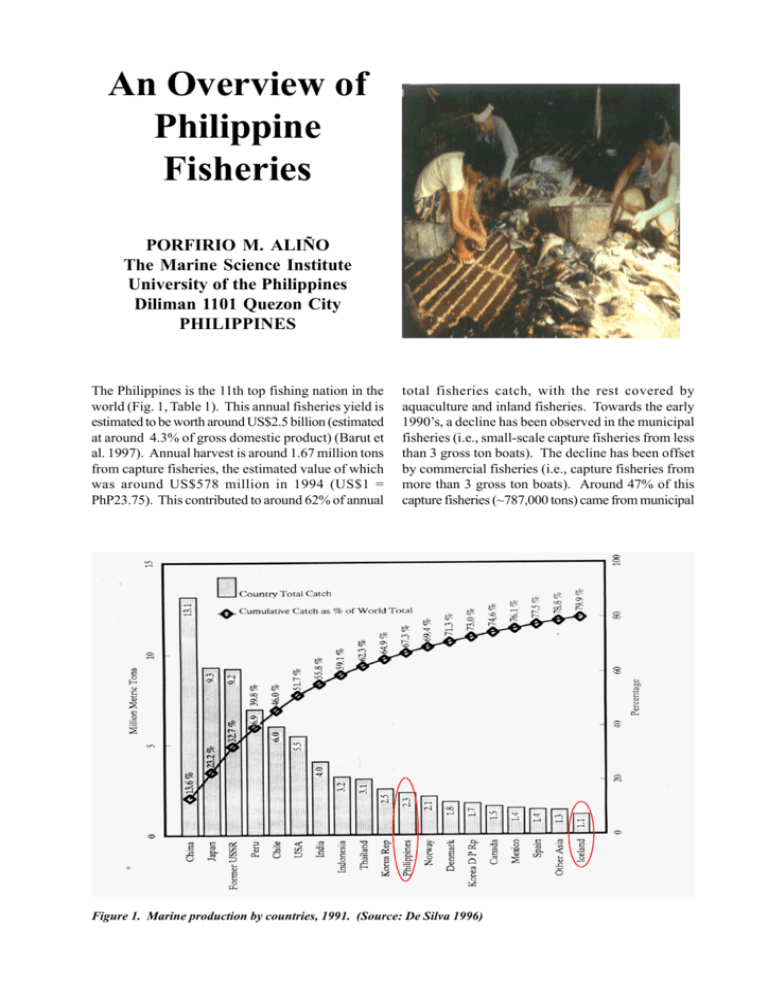

The Philippines is the 11th top fishing nation in the

world (Fig. 1, Table 1). This annual fisheries yield is

estimated to be worth around US$2.5 billion (estimated

at around 4.3% of gross domestic product) (Barut et

al. 1997). Annual harvest is around 1.67 million tons

from capture fisheries, the estimated value of which

was around US$578 million in 1994 (US$1 =

PhP23.75). This contributed to around 62% of annual

total fisheries catch, with the rest covered by

aquaculture and inland fisheries. Towards the early

1990’s, a decline has been observed in the municipal

fisheries (i.e., small-scale capture fisheries from less

than 3 gross ton boats). The decline has been offset

by commercial fisheries (i.e., capture fisheries from

more than 3 gross ton boats). Around 47% of this

capture fisheries (~787,000 tons) came from municipal

Figure 1. Marine production by countries, 1991. (Source: De Silva 1996)

Table 1. Asian countries’ artisanal fishing sectors. (Source: De Silva 1996)

fisheries and the rest (~885,000 tons) was from

commercial fisheries (Barut et al. 1997) (Table 2;

Figs. 2, 3). In the medium term development plan of

the Philippines (including the next 5 years), it is

projected that no further increases from municipal

fisheries are expected. Thus, it was emphasized in

the Philippine’s National Fisheries Agenda to arrest

the decline in municipal fisheries and sustain the

present levels. Commercial capture fisheries

production was expected to increase by around 10%

Figure 2. Philippine marine fisheries production, 1950-1994. (Source: BFAR and BAS Statistics 1994, in Barut

et al. 1997)

Table 2. Marine fisheries production (top) and annual economic benefits from fisheries (bottom) in the Philippines,

1996. (Source: White and Cruz-Trinidad 1998)

to compensate for the deficits from increased demand

due to population growth. Aquaculture was also

expected to account for over 35% of the total

harvests, and hence, complement overall fisheries

production (Aguilar 2001). By the year 2010, if the

annual population growth of the Philippines continues

at 2.4%, then a considerable deficit in fisheries yield

relative to per capita consumption is expected.

from surplus production models by Silvestre and Pauly

(1986) of pelagic catch and of the demersal catch

(Dalzell 1996), the Philippines has well exceeded the

estimated MSY. The calculated annual rent

dissipation from overfishing was estimated at around

US$130 million for demersal fisheries and around

US$290 million for small pelagics (Trinidad et al. 1993)

(Figs. 6 and 7).

As an archipelagic state composed of around 2,100

islands, the Philippines extends around 2,000 km north

to south from 4o05’ to 4o30’. The total territorial

waters cover around 2.2 million km2 and the shelf

area is around 184,600 km2 (Barut et al. 1997) (Fig.

4). Silvestre (1989) cites an initial delphi analyses of

the various fishing areas in the Philippines and shows

that most of these areas are already fully- to overexploited (Fig. 5). Based on some general estimates

One may note that since the Philippines is found in

the most diverse region in the marine world, its

multispecies and multigear fisheries (Fig. 8) manifests

the varied range of problems in the resources and its

developing economy. Thus, the country’s fisheries

experience indications of shifts in species composition

together with a decline in fisheries yield (see Dalzell

et al. 1987).

Figure 3. Philippine marine fisheries production, 1991-2000. (Source: DA-BFAR Statistics 2000)

The issues and concerns mentioned earlier can best

be exemplified by some of the following case

examples:

1. Lingayen Gulf and Manila Bay: too many

fishers and environmental stress

One of the common features in many fishing areas is

how the varying degrees of environmental stress

induced by human impacts interact with fisheries

25.00

0.0

-200.0

20.00

North Latitude (degrees)

-1000.0

-2000.0

-3000.0

15.00

-4000.0

-5000.0

-6000.0

10.00

-7000.0

-8000.0

5.00

-9000.0

-10000.0

Depth (meters)

0.00

110.00

115.00

120.00

125.00

130.00

135.00

East Longitude (degrees)

Straight Baselines

Treaty Limits

200 n.mi. E.E.Z.

Kalayaan Claim

-

Republic Act No. 3046 amended by R.A. 5446

Treaty of Paris (1898)

Presidential Decree No. 1593; 1978

Presidential Decree No. 1595; 1979

Figure 4. Schematic territorial boundaries and bathymetry map of the Philippines. (Source: Aliño, 1998)

Figure 5. Heavily exploited areas in the Philippines. (Source: Tandog-Edralin et al. 1987, in White and CruzTrinidad 1998)

overexploitation (e.g., siltation together with pollution

in Lingayen Gulf and Manila Bay; Padilla and

Morales 1997, Pauly and Chua 1988). The most

prevalent fisheries concern is the condition that is

referred to as ‘malthusian overfishing’. This condition

often related to an increasing density of fishers’

population and leads to using more efficient but

destructive fishing practices such as blastfishing

(Pauly et al. 1989). In addition, the competition

between commercial and municipal fishing activities

within municipal waters has been consistently seen

as one of the major concerns (Table 3; Figs. 9 and

10).

2. Municipal fisheries vs commercial fisheries

Due to the overexploited state in the coastal areas

and the need to regulate fishing effort (i.e., municipal

waters within 10 to 15 km from the shore), illegal

access by the commercial fleets has been seen as a

major problem in the fisheries sector. Smith et al.

(1983) has highlighted this quite well for San Miguel

Bay (Table 4). Note that the 89 trawlers belonged

only to 40 households (with 42% of its total value)

whereas the 2,300 small-scale fishing gears belonged

to 3,500 fishers (Silvestre and Pauly 1997). This social

equity and uneven competition have been considered

characteristic not only in the Philippines, but also in

many other coastal fisheries of developing countries.

Thus, solutions require greater empowerment

mechanisms (e.g., community-based efforts for

improved enforcement), which, to some extent, have

been initiated through some of the decentralization

devolution mechanisms of the Philippine local

government code of 1992.

Unfortunately, the small-scale municipal fisheries

sector also requires considerable effort reductions in

order to have any significant change to mitigate for

the decline of the fisheries resources (Hilomen et al.,

unpubl. rep.). As mentioned earlier, malthusian

overexploitation, together with the marginalization of

Figure 6. Surplus production models of the Philippines’ small pelagic and demersal fisheries. (Sources: Silvestre

and Pauly 1986; Dalzell et al.1986, in Silvestre and Pauly 1997)

Figure 7. Trend of catch per unit effort since 1948. (Source: Dalzell et al. 1987, in White and Cruz-Trinidad 1998)

the municipal fishers, have led them further to

desperate measures for more effective and

destructive fishing practices (e.g., blast fishing, poison

fishing) (Pauly et al. 1989).

3. Capture fisheries and mariculture

Due to the expected stagnation of capture fisheries

in the coastal areas and, on the other hand, with a

projected continuous increase in population, cheap

fish protein food may be less available in future

(Bernacsek 1987). Hence, mariculture has been seen

as the logical panacea to augment the fisheries

deficit. This suggestion, however, has been wrought

with problems such as the issue of degradation of

important fisheries habitats. In the Philippines,

fishpond conversion of mangrove areas has been

identified as one of the major cause of mangrove

Figure 8. Some fishing gears used in the Philippines. (Source: SEAFDEC 1995)

destruction (Aliño et al. 1998) (Figs. 11

and 12). Recently in the Lingayen Gulf,

the introduction of fish pens and fish

cages brought about serious problems.

Aside from the problems of water quality

and fish kills due to unrequlated

aquaculture activities (Fig. 13), further

displacement of fishers has occurred in

addition to the unfair access

arrangements in the commons (Verceles

et al. 2001).

4. Transboundary issues: pelagic

stocks and disputed areas

Morgan and Valencia (1983) shows the

importance of the Philippines in the

migration route of yellow fin tuna and

illustrates some important concerns in

shared stocks (e.g., round scads between

the Philippines and Malaysia in the South

China Sea and, in addition, Indonesia, in

the Sulu-Sulawesi Sea region) (Figs. 14

and 15). Ganaden and Stequert (1987)

reported on the innovation by the

Filipinos’ introduction of the payao (a

fish aggregating device; Fig. 16) and

suggested that catch rates in the

Philippines may be beyond their potentials

and may also have signs of growth

overfishing.

- bottom set gillnet

- fishtrap

- hook and line

- baby trawl

- lamp

- tabang

- bira-bira

- surface/floating gillnet

- sagap

- fish corral

Figure 9. Spatial patterns of exploitation of various municipal

fisheries in the Lingayen Gulf, Aug-May 2001. (Source: Hilomen

and Jimenez 2002)

Table 3. Comparison of the estimates of catch rates (in kg per trip) obtained for selected municipal fisheries in

Lingayen Gulf between 1985 and 2001. (Source: Hilomen & Jimenez, unpubl. rep.)

Fishery

2000-2001 d

1985

% decrease

A. Municipal

15.25 a

Gillnet

11.04

38.16

H/L

7.08

a

3.15

124.51

Fish corral

4.35 a

0.90

384.63

1.75

23.15

a

Fish trap

2.1

Baby trawl

31.3 b

14.68

113.17

Danish seine

26.8 a

14.17

89.18

Trawl

31.8 c

15.37

106.90

B. Commercial

a

Calud et al. 1989

b

c

Mines 1986

Value estimated in 1987 in Ochavillo et al. 1989

d

This study. CPUE in kg mn-hr-1 were translated to kg per trip by

multiplying CPUE with average number of actual hours spent fishing

each day.

20,000

18,000

16,000

Yield (mt)

14,000

12,000

1995

10,000

8,000

6,000

2000

4,000

2,000

-

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

Fishing effort (HP)

Figure 10. Sustainable yield and status (with years indicated) of combined commercial and municipal fisheries in

the Lingayen Gulf. (Source: Hilomen & Jimenez, unpubl. rep.)

An extrapolation by Ganaden and Stequert (1987)

for a 5-degree grid fishing area shows that compared

to other areas in the world, the Philippines has around

2 to 4 times more yield than the most productive

fishing area in the Atlantic (yield ~28,400 Mtons per

5o square), in the East Pacific (24,500 Mtons per 5o

square), and in the Indian Ocean (17,600 Mtons per

5o square). Aliño et al. (1998) have provided some

initial evidence of the possible decline of tuna stocks

especially in the South China Sea area.

Table 4. Summary of data on the duality of the fisheries in San Miguel Bay, Philippines. (Source: Smith et al. 1983)

Figure 11. Mangrove resource decline in the Philippines. (Source: World Bank 1989, in White and Cruz-Trinidad

1998)

Summary and conclusions

Silvestre (1989) provided some

recommendations on tackling the

various issues and concerns on

Philippine Fisheries:

1. Enhance capabilities of

Fisheries Management councils at

all levels specially through the

establishment of National and

Regional Fisheries Councils. To

date, with Republic Act 8550 (the

Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998),

the Fisheries and Aquatic

Resources Management Councils

(FARMCs)

have

been

Figure 12. Proliferation of fishpens in the Lingayen Gulf. (Photos by Dr. Gil

S. Jacinto)

this story was taken from www.inq7.net

URL: http://www.inq7.net/brk/2002/feb/02/text/brkoth_41-p.htm

Fish kill hits coastal town of Pangasinan

Posted:2:40 PM (Manila Time) | Feb. 02, 2002

By Inquirer News Service

BOLINAO, Pangasinan – A massive fish kill hit this coastal

town as millions of pesos worth of cultured bangus (milkfish)

died suddenly.

Mayor Jesus Celeste said there was no estimated damage

yet although one operator with 10 fish cages was said to

have lost about P4-million worth of bangus, while another

lost about P1-million worth.

Many operators of fish cages, as a result, have been

hastily harvesting their remaining stocks.

There are about 400 fish cages and 200 fish pens in

Bolinao, but the most affected were those in Barangays

Guiguiwanen and Luciente II.

Celeste said somebody could have poured a chemical

that poisoned the bangus. White fluid was found in the fish

cages, he said.

"Why was only one area affected if the cause was

pollution? Why not the entire Bolinao?" he asked.

He sought the help of the University of the Philippines

Marine Science Institute, which maintains a laboratory in

the town, to examine the chemical that caused the fish kill.

The incident occurred amid protests from residents about

the proliferation of fish cages and pens in Bolinao.

In a letter to the municipal council, Margaret Celeste,

elder sister of the mayor, said fish cages have been polluting

the waters off Barangays Lambes, Zaragoza, Catungi,

Tara, Culang, Luna and Luciente II, and parts of Barangays

Luciente I and Lucero.

"The areas occupied by fish cages and pens have

become polluted due to excessive concentration of fish

feeds, and the water quality (there) has deteriorated,"

Margaret Celeste said.

She warned that the presence of these fish cages "might

The fish cages and pens have already affected the

navigational route of the residents of Santiago Island,

especially at night, the mayor's sister said. Yolanda Fuertes,

PDI Northern Luzon Bureau

©2002 www.inq7.net all rights reserved

Figure 13. News of the recent fish kill in Bolinao, Pangasinan, downloaded from www. inq7.net on Feb 2, 2002.

(Photos were from www.upmsi.ph)

institutionalized by law. Unfortunately, they are mainly

a consultative body and would require improved ways

of making them more effective in actual management

interventions in the ground.

2. There is a need to clarify the management goals

that fisheries management programs often confuse

the management concerns that deal with intermediate

causes (e.g., overexploitation of fisheries and habitat

destruction) and those that deal with the root causes

(e.g., poverty, population growth, social equity, political

economy). Aside from the clarification of these goals

and objectives, it is crucial that appropriate

stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities be identified

to contribute to coordinated, integrated and

complementary outcomes.

Figure 14. Inferred migratory route of some tuna species passing through the Philippines. (Source: Morgan and

Valencia 1983)

3. Pursue innovative ways of reducing fishing effort

and more effective ways of enforcement and

compliance. Considering the dire depauperate

condition of the Philippines and widespread hunger

and deprivation in its social development, controlling

fishing effort requires more than the usual command

and control monitoring, control and surveillance

mechanisms of developed states. Much of the

succesful initiatives tended to provide social pressures

from the community through a changed social view

of community stewardship. A broader compliance

to local and national ordinances can be improved if

political-will is demnstrated by the local government.

On the other hand, many broad based organized

community (e.g., through militant peoples

organizations) or through citizens watch programs

known as Bantay Dagat (sea watchers or local

community coast guards) have also been succesful.

Though only documented in fewer cases in the

Philippines, some communities still assert some of

their local beliefs (akin to traditional ecological

knowledge and wisdom) as a guide for their fishing

practices (Mangahas 1993).

4. Explore incentives for livelihood-linked programs

to sustain resource management and disincentives for

sustainable practices. Due to the broader

development concerns prevalent in developing

countries, regulating fishing as a crucial livelihood for

the sustenance of fishers requires effective incentives

to shift towards sustainable practices. Some success

has been shown for areas where some fishers have

shifted towards some ecotourism related activities

involving marine sanctuaries where resource

extraction has been minimized (Vogt 1997). In

addition, it has been suggested that resource

enhancement activities involving community

stakeholders has shown some promise. Such

experiences in learning by doing as part their livelihood

and as stewardship responsibility creates a greater

social pressure for unsustainable practices. Reducing

product acceptance derived from unsustainable

livelihood practices (e.g., blast fishing and poison

fishing) and as compared to more acceptable

ecolabelled goods and services also offer

complementary value-added incentives.

Figure 15. Some shared pelagic stocks around the Philippines especially in the South China Sea. (Source: Morgan

and Valencia 1983)

5. Encourage joint ventures in international waters

and consider incentives in lightly exploited international

areas. The broad Philippine fisheries experience in

the region may offer the problems of its local fisheries

resource depletion to explore lightly exploited areas

in the Pacific international waters areas with other

regional partners (e.g., Indonesia and Papua New

Guinea). Improvement of the private sector and state

interaction needs to be explored further especially in

facilitating goodwill and clarifying mutually beneficial

trade agreements.

Figure 16. A ‘payao’ made of bamboo (based on de

Jesus 1982). (Source: Aprieto 1995)

6. Improve effectiveness of enhancement and

rehabilitation through an ecosystem and integrated

coastal management approach. Some reseeding

efforts and mangrove enhancement initiatives have

met with less success due to the inappropriate context

that they have been undertaken. Thus sea ranching

without sufficient efforts to regulate access and area

control (e.g., with a complementary marine sanctuary

area) or proper grow out educated cooperators would

not be sustainable. In addition, enhancement areas

situated in areas where conflicts in general usage of

the zones (e.g., international ports and industrial

discharges or possible pollution sources) would

jeopardize enhancement and rehabilitation. As shown

in the example for mariculture, more and more

fisheries management concerns of municipalities’ are

now being approached as part of its’ integrated coastal

development plans.

References

Aguilar GD (2001) The national integrated research

development extension agenda and program for

capture fisheries. In Int Sem Responsible capture

fisheries in coastal waters of Asia: case studies

and researches for sustainable development and

management of tropical fisheries, 24-27 Sept 2001,

College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences,

University of the Philippines in the Visayas, Miagao, Iloilo, Philippines, p 3 (Abstracts). Japan Society

for the Promotion of Science

Aliño PM (1998) Transboundary diagnostic analysis

for the South China Sea - Philippine country report

Aliño PM, Nañola CL, Ochavillo DG, Rañola MC

(1998) The fisheries potential of the Kalayaan

Island Group, South China Sea. In Morton B (ed)

Proc 3rd Int Conf Marine Biology of the South

China Sea, Hong Kong, 28 Oct - 1 Nov 1996, pp

219-226. Hong Kong University Press, Hong

Kong

Aprieto VL (1995) Philippine tuna fisheries: yellowfin

and skipjack. University of the Philippines Press,

Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines, 251 p

Barut NC, Santos MD, Garces LR (1997) Overview

of Philippine marine fisheries. In Silvestre G, Pauly

D (eds) Status and management of tropical coastal

fisheries in Asia, ICLARM Conf Proc 53: 62-71

Bernacsek G Principal fisheries development policy

issues for the five-year development plan of the

Philippines. Paper presented at the National

Fisheries Policy Workshop, 16-20 Mar 1987,

Baguio City

Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and

Aquatic Resources, DA-BFAR (2000) Fisheries

profile 2000. Manila, Philippines

Dalzell P (1996) Catch rates, selectivity and yields

of reef fishing. In Polunin NVC, Roberts CM (eds)

Reef fisheries, pp 161- 192. Chapman and Hall,

London

Dalzell P, Corpuz P, Ganaden R, Pauly D (1987)

Estimation of maximum sustainable yield and

maximum economic rent from the Philippine small

pelagic fisheries. Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic

Resources Tech Pap Ser 10(3), 23 p

De Silva SS (1996) A review of the major trends in

Asian fisheries. In De Silva SS (ed) Perspectives

in Asian fisheries - a volume to commemorate the

10th anniversary of the Asian Fisheries Society,

pp 85-104. Asian Fisheries Society, Makati City,

Philippines

Ganaden R, Stequert B (1987) Tuna fisheries in the

Philippines. Paper presented at the IPTP Tuna

Working Group, Aug 1987, Manila, Philippines

Hilomen VV, Nañola CL, Dantis AL (2000) Status

of Philippine reef fish communities. Proc

Workshop Status of PhilippineRreefs, p 14

(Abstract)

Hilomen VV, Jimenez L (2001) Resource and social

assessment of Lingayen Gulf: Capture fisheries

(unpublished report)

Manprasit A, Siriraksophon S, Masthawee P,

Chokesanguan B, Sae-Ung S, Soodhom S, Dickson

JO, Matsunaga Y (1995). Fishing gear and methods

in Southeast Asia: III. The Philippines. Training

Department Southeast Asia Fisheries

Development Center (SEAFDEC)

Mangahas M (1993) Indigenous coastal resources

management: the case of the hataw fishing in

Batanes. Center for Development Studies,

University of the Philippines, Quezon City (MA

Thesis)

Morgan JR, Velencia MJ (1983) Atlas for marine

policy in Southeast Asian Seas. University of

California Press, Berkeley

Padilla JE, Morales AC (1997) Evaluation of

fisheries management alternatives for Lingayen

Gulf: an options paper. In Studies on Lingayen

Gulf, Final report of The Philippine Environmental

and Natural Resources Accounting Project

(ENRAP-Phase IV), 32 p, 20 tables, 6 figures

Pauly D, Chua T-E (1988) The overfishing of marine

resources: socioeconomic background in Southeast

Asia AMBIO 17: 200-206

Pauly D, Silvestre GT, Smith IR (1989) On

development, fisheries and dynamite: a brief review

of tropical fisheries management. Nat Resour

Modelling 3(3): 307-329

Silvestre GT (1989) Philippine marine capture

fisheries: exploitation, potential and options for

sustainable development. Working Paper No 48,

Fisheries Stock Assessment, CRSP. International

Center for Marine Resource Development, The

University of Rhode Island, Kingston, Rhode

Island, 87 p

Silvestre GT, Pauly D (1986) Estimate of yield and

economic rent from Philippine demersal stocks

(1946-1984). Paper presented at the IOC/

WESTPAC Symp on Marine Science in the

Western Pacific: the Indo-Pacific Convergence,

1-6 Dec 1986, Townsville, Australia

Silvestre GT, Pauly D (1997) Management of tropical

fisheries in Asia: an overview of key challenges

and opportunities. In Silvestre G, Pauly D (eds)

Status and management of tropical coastal fisheries

in Asia, ICLARM Conf Proc 53: 8-25

Smith IR, Pauly D, Mines AN (1983) Small-scale

fishing of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: options for

management and research. ICLARM Tech Rep

11, 80 p

Trinidad AC, Pomeroy RS, Corpuz PV, Aguero M

(1993) Bioeconomics of the Philippine small

pelagic fishery. ICLARM Tech Rep 38, 78 p

VercelesLF, McManus LT, Aliño PM ( 2001)

Participatory monitoring and feedback system: an

important entry towards sustainable aquaculture

in Bolinao, northern Philippines. Sci Diliman, pp7887

Vogt PH (1997) The economic benefits of tourism

in the marine reserve of Apo Island, Philippines.

Paper presented at the 8th Int Coral Reef Symp,

June 1997, Panama, 7p

White AT, Cruz-Trinidad A (1998) The values of

Philippine coastal resources: why protection and

management are critical. Coastal Resources

Management Project, Cebu City, Philippines, 96 p