Mortar as Grout for Reinforced Masonry

advertisement

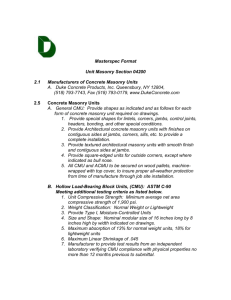

Mortar as Grout for Reinforced Masonry Phase 1 Report April 2005 RBA Project 8379 Mortar as Grout for Reinforced Masonry Phase 1 Report Prepared for: International Masonry Institute National Lime Association Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers Local No.1, New York, NY National Concrete Masonry Association Research and Education Foundation Prepared by: David T. Biggs, P.E. Ryan-Biggs Associates, P.C. 291 River Street Troy, New York 12180 (518) 272-6266 (518) 272-4467 (fax) dbiggs@ryanbiggs.com www.ryanbiggs.com TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 BACKGROUND . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Historical . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Codes and Standards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Previous Research Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 TESTING CONCEPT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 MATERIAL CHARACTERIZATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Sand . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Grout . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mortar Fill and Pourable Mortar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Concrete Masonry Units . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Reinforcement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Compressive Strength of Masonry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 13 13 14 16 16 16 TESTING RESULTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Pull-Out Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Failure Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bond Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 18 21 23 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Pull-Out Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Tests of Bond Between Fill Material and CMU . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33 COMMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 CONCLUSIONS/RECOMMENDATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C APPENDIX D APPENDIX E APPENDIX F Sand Test Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Grout and Mortar Fill Test Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Concrete Masonry Unit Test Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Pull-Out Test Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bond Test Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii A-1 B-1 C-1 D-1 E-1 F-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mortar used as grout for reinforced masonry for grout in commercial construction is a topic of major interest to many masons that use low-lift grouting techniques. While not specifically allowed by model codes and standards, it is commonly used on projects. Residential standards in the United States have allowed Type S and Type M mortar tempered to a “pourable” consistency for grouting for many years. A pourable consistency has a slump of approximately 6 inches. This report documents Phase 1 testing of a research program aimed at evaluating mortar as a substitute for grout for use with vertical reinforcement. Phase 1 includes a series of pull-out tests and bond shear stress tests performed on prism-sized samples. This phase was intended to evaluate only vertical reinforcing using small-scale samples to determine if full-scale testing is recommended and the possible parameters of that testing. Samples were constructed at facilities of Bricklayer and Allied Craftworkers, Local 2 in Albany, New York. Testing was performed at commercial laboratories in Watervliet, New York, Scotia, New York and at the National Concrete Masonry Association. Several mixes were compared using reinforced CMU: 1. Type N and Type S mortars as commonly mixed for setting units. 2. Type N and Type S mortars that were tempered to a pourable consistency. 3. ASTM C 476 grout. 4. Type S mortar tempered to the consistency of grout. Type N mortar did not provide acceptable results, primarily due to its low strength. Type S mortar performed better in the pull-out tests than the “pourable” mortars that are allowed in residential codes. However, based upon the tests results, Type S and Type M mortar could be an acceptable substitute for grout provided the mix achieves at least 2000 psi compressive strength when tested as a grout prism. Phase 2 full-scale testing is recommended using Type S and Type M mortars in a modified low-lift application. The test results suggest some topics for additional consideration. Some of these include: 1. The strength of the fill material (mortar, pourable mortar, or grout) that encases the reinforcement affects the development length of the reinforcement. MSJC formulas for lap splices do not adequately account for the strength of the fill material. 2. The shrinkage characteristics of the fill material should be evaluated to determine their importance in achieving adequate bond shear strength. iii INTRODUCTION The Masonry Standards Joint Committee (MSJC)1 requires grout for use in reinforced masonry for commercial construction. Grout is used to fill cells of hollow masonry and fill cavities of composite construction. However, the majority of its use is to encase reinforcement. For residential construction, some model codes allow the use of “pourable” mortars. “Pourable” mortars are created by adding sufficient water to the mortar so that the mix can be poured into the masonry. In spite of codes and standards, it is common in some regions of the United States for various masonry contractors to substitute mortar for grout in commercial construction. The mortar is used as traditionally mixed without additional water added. Dependent upon the jurisdiction, the mortar substitution requires the acceptance of the designer as well as the building official. The logic for the substitution is that mortar and grout have similar constituent materials and therefore should perform similarly. Masonry contractors who prefer to use mortar as grout along with the low-lift technique cite the following reasons: 1. Reduces installation costs for low-lift applications when the masonry is to be grouted. 2. Reduces the number of mixers used since industry standards generally require separate mixing of mortar and grout. 3. Eliminates contamination of core cells that can occur when using two different materials. 4. Increases the chance of placing consistent material by grouting course by course in walls when there are numerous mechanical trade penetrations, reduced overhead clearance, and general access restrictions to the top of the wall. 5. Improves delivery of materials on high-rise buildings for infill walls. Contractor distribution of different materials is reduced. For contractors that prefer the high-lift grouting technique, using mortar as grout is generally not done or limited to filling at openings with embedded hardware such as door jamb anchors. The material standard in the United States for masonry grout is ASTM C 4762. Within the standard, there are two types of grout: fine grout and coarse grout. Fine grout has sand aggregate, portland cement, and lime; coarse grout uses pea gravel in addition to the sand. The material standard for mortar is ASTM C 2703. The standard allows three cement options for mixing mortar. These include: 1. Portland cement and lime. 2. Masonry cement. 3. Mortar cement. In all three options, sand is used as the aggregate. Page 1 Purpose of this Report This report documents the research that was initiated to examine the performance of portland cement and lime-based mortars in reinforced masonry as an alternative for grout to encase vertical reinforcement. Portland cement and lime-based mortar is evaluated since it most closely replicates the constituent materials of fine grout. Natural sand was used as the aggregate. The study is limited to concrete masonry units (CMU) used in a modified low-lift grouting application. Page 2 BACKGROUND Historical A. Grouting began in the United States after the 1933 Long Beach California earthquake damaged many unreinforced brick buildings. The use of reinforcement in the walls made grout necessary. Initially, all grouting was performed course by course. Six-foot lengths of reinforcement were used; four feet were grouted each day and two feet were left for a lap splice. In northern California, masonry contractors wanted to speed up construction and proposed constructing the masonry full height and then grouting the wall full height. With limitations, the method was accepted by the State of California 4. From this beginning, two grouting techniques were developed for the United States: low-lift and high-lift. Low-lift grouting occurs incrementally with the installation of the masonry. Standards limit this grouting to a maximum pour of 5 feet. High-lift grouting allows the masonry to be constructed and grouted in pours greater than 5 feet using lifts that are a function of the grout type and the size of the cell or cavity to be filled. In the 2005, the MSJC changed its criteria so that the maximum lift heights could increase from 5 feet to as much as 12 feet 8 inches. Pour heights were not changed. B. Amrhein 5 reported that grout slumps for high-lift grouting were determined by the Office of the State Architect, Structural Safety Section, Circular Number 10, Clay Brick Masonry, High Lift Grouting Method. The circular stated “The slump of the grout should be varied depending upon the rate of absorption of the masonry units and temperature and humidity conditions. The range should be from 8 inches for units with a low rate of absorption (30 to 40 grams per minute) up to 10 inches for units with a high rate of absorption (80 to 90 grams per minute).” Thus, high-slump grout was developed for high-lift grouting to flow into the voids of the masonry units and around reinforcement. This became the grout standard for both low-lift and high-lift grouting. The absorption rates noted are interesting in that industry recommendations are to pre-wet bricks before construction whenever the initial rate of absorption (IRA) exceeds 30 grams per minute per 30 square inches 6. Thus, if the bricks are pre-wetted and the IRA is reduced to less than 30, the California information would seem to justify lower slump grouts. C. Isberner7 reported in 1982 that grout had not been extensively researched. He states “..it is unfortunate we disallow certain practices and materials on little or no evidence. Some past and recent research, however, shows there is much to be learned regarding the role of grout in reinforced masonry”. Furthermore, “Although many grouted reinforced masonry structures are now in existence, the specifics of grout design and use are relatively unfounded.” Page 3 He suggested that “Grouts be designed, specifically, to develop the specification strength at the required test age when acceptable test molds and specimens are used.” He also noted that test data indicates that low water content grouts (2 to 3 inch slump) could develop compressive strengths in the 2000 psi range. Lastly, Isberner recommended research to show alternative methods of grouting reinforced masonry. D. In many areas of the country, high-lift grouting is not commonly used. Thus, the question arises as to whether a high-slump grout is necessary for those applications that use low-lift grouting techniques. If not, is mortar satisfactory for grout for low-lift applications? There have been no reported incidences found in the literature of structural failures attributed to mortar being used as grout for vertical reinforcement. Failures associated with grouting are generally attributed to missing or inadequate filling of masonry. The properties of the grout were not reported. Codes and Standards In the 1982 Uniform Building Code 8, mortar was acceptable as a substitute for grout for chimneys and fireplaces. This was subsequently deleted in the 1985 edition. Residential codes from the Council of American Building Officials (CABO)9 allowed Type S or Type M mortar with water added to be used as grout. CABO became part of the International Code Council, and its International Residential Code (IRC)10 also allows Type S or Type M mortar with water added to be used as grout. Previous Research Work A. To support the use of mortars in residential construction, previous research11 was done in 1991 by the National Concrete Masonry Association (NCMA) to evaluate mortar as fine grout. They used Type S and Type M mortars with sufficient water added to create a “pourable” mixture that achieved a slump of 7 to 9 inches. The pourable mortars were compared to three grout mixes with similar slump. The three grout mixes contained only cement and sand. The aggregate ratios in the grouts were varied to achieve compressive strengths similar to the mortars. The test setup was not described; it was noted a No. 5 bar was pulled in tension from the specimens and tension bond strengths were calculated. Comparing the data for pourable Type S, PCL (portland cement- lime based) mortar and ASTM C 476 fine grout: 1. The compressive strength for the grout was 10 percent higher than for the pourable mortar. 2. The grout only achieved tension bond strengths 6 percent higher than the pourable Type S mortar. The report concluded that further research was necessary but that pourable mortars “could become an effective substitute for grout.” B. In 1998, a report prepared by Brown12 at Clemson University reported using mortar as grout in reinforced hollow clay walls. The tests obtained tension bond strengths between the Page 4 reinforcement and grout developed from three methods of filling the cell space around reinforcing in hollow clay units and compared them with each other. The three methods included grouting with standard grout, “slushing” with mortar, and “souping” with mortar. The author indicated that “slushing” involved filling the cells of the masonry with mortar as the walls were laid. “Souping” mortar involved adding sufficient water to produce a slump of about 10 inches. Specimens were tested in pull-out mode; some were tested in direct tension, and others were tested to evaluate lap splices. The direct tension pull-out tests developed flexural tension cracks in the masonry along the center of the rebar that clearly reduced the pull-out strength. The report noted that this phenomenon would not be expected in actual walls and was simply a result of using a test specimen that produced an effect that was not anticipated. They indicated the results of the pull-out tests should not be considered other than for comparison with each other. The mortar used to fill the masonry was a Type S masonry cement mortar. The compressive strength from mortar cubes was between 1,076 and 1,802 psi for the “slushed” mortar. The “souped” mortar tested as grout achieved a strength of over 4,500 psi. The grout strengths were unusually high at over 11,000 psi. No general conclusions were listed. However, a notable observation was that of the 36 tests conducted, 35 produced tension bond strengths that developed tensile bar strengths exceeding the allowable tensile strength of the rebar. The single test that did not achieve allowable stress was observed after testing to be poorly consolidated. The “slushed” mortar samples produced results in the pull-out tests slightly less than the “souped” mortar samples. The grout tests resulted in the highest pull-out results. However, the ratio of the compressive strength of the grout to the “souped” mortar was approximately 2.44, whereas the ratio of the pull-out strengths was 1.45. Thus, the mortars performed very well in comparison to the grout. Page 5 TESTING CONCEPT Goals While the compressive strength of masonry is important, the primary concern of this study is how the masonry, and in particular, the mortar that is used to fill the cells (referred to as mortar fill), is likely to respond to tension in the reinforcement. The ability of the masonry to develop tension in the reinforcement is related to the ability of the mortar fill to bond to the CMU and the reinforcement. This research is intended to study mortar as grout in reinforced masonry by testing the pull-out strength of vertical reinforcement and the bond strength of the mortar fill to the units. The study is being performed at an elemental level rather than with full wall tests. The results will be used to determine if further large-scale testing is appropriate and worthwhile. Definitions For the purpose of this research, the following definitions are used. Mortar fill: ASTM C 270 mortar used as mixed with no water added. Pourable mortar: ASTM C 270 mortar with water added to produce a pourable consistency. Grout: ASTM C 476 grout with a slump of 8 to 11 inches. Fill material: The generic term used for mortar fill, pourable mortar, and grout to make specimens. Tests Two types of tests were performed. A. Pull-Out Tests No specific ASTM test was used for this work. Small scale tests were developed in 1996 by Ryan-Biggs Associates (RBA) for specific projects to compare the performance of mortar fill to grout when prism-type samples containing a reinforcing bar are exposed to pull out of the reinforcement. That testing concept is the basis for this portion of the research and is similar to the procedure used by Richart 13 to test for tension bond strength. The tests used were not intended to represent actual wall performance but were selected as more representative than pure tension tests of lap splices. A key component of the current study is to create a test that forced a failure in the fill material under pull out mode. From those results, it would be possible to compare the performance of the mortar fill and pourable mortar with the grout. It was decided to place the masonry units in compression rather than use tension samples. While neither the previous tension tests nor this work adequately represents walls subjected to flexure, it was decided that the proposed tests would serve to adequately compare mortar fill, pourable mortar, and grout under similar test conditions. Therefore, from these tests a decision could be made as to whether further full-scale tests were warranted that represent flexural walls and tension tests for shear walls. Page 6 In this portion of the study, the performance of the mortar fill is to be judged based upon its: 1. Capacity to develop tension in the reinforcement. 2. Capacity to develop tension in the reinforcement relative to code requirements. 3. Capacity to develop tension in the reinforcement in comparison to grout. Testing was performed at Materials Characterization Laboratory, a commercial testing laboratory in Scotia, New York. Pull Out Procedure 1. Samples were prepared as shown in Figure 1 with two CMU stack bonded. They were prepared by a journeyman mason from Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers (BAC) Local #2 in Albany, New York. The jacking plate was added prior to the test and was set dry on the sample. Figure 1 Pull-Out Test Specimen Page 7 2. Samples were constructed inside the BAC facilities (Photograph 1). The air temperature at the time of construction was approximately 75°F, with a relative humidity of approximately 85 percent. Photograph 1 For consistency, all samples were made similar to ASTM C101914 prisms by rodding the fill material 25 times for each lift. Each sample had three lifts. 3. Each sample was created from a sawn half unit of 8-inch CMU; units had either a square end or a sash block end. Construction was similar to ASTM C 1019 which contains information related to constructing prisms. Samples were first constructed two units high and allowed to cure for 21 days. They were subsequently filled with mortar fill, pourable mortar, or grout and allowed to air dry for 7 days; no moisture was applied. After 7 days, they were transported to the testing facility and allowed to continue air curing. Due to the large number of samples and the presence of reinforcement, the samples were air cured rather than being placed in a plastic bag as recommended by ASTM. The fill material in the samples were 31days old when tested. 4. Samples were tested in a tensile testing machine. Photographs 2 and 3 show the test configuration. The top jacking plate was fitted with spacer bars to allow the bearing of the steel on the face shells and webs of the CMU and not on the fill material so as not to restrict slippage of the fill material from the CMU. Page 8 Photograph 2 Photograph 3 Figure 2 shows the test setup graphically and the free-body diagram of the load application. Figure 2 - Pull-Out Specimen in Test Frame 5. Test results were recorded for load versus reinforcement slippage and elongation until maximum load was applied. The test equipment pulled the reinforcement at a constant rate of 0.2 inches per minute. 6. Samples were photographed and the types of failure categorized. Page 9 B. Tests of Bond Between Fill Material and CMU No specific ASTM test was available to measure this bond property. The test method in this study followed the procedure outlined in the Department of State Architect of California requirements in California State Chapter 2405(c)3.C. The test method is described in Concrete Masonry Association of California and Nevada document, “Recommended Grouting Procedure for Hollow Concrete Masonry Constructed Under CAC Title 24.” Prism samples were prepared similar to the pull-out test samples except without the reinforcing bar. After approximately 40 days, prisms were delivered to the National Concrete Masonry Association in Herndon, Virginia. Core samples (6-inch nominal) were taken from the prisms (Photograph 4) and tested in their laboratory. The intent was to test for bond shear strength between the fill material and the CMU. Theoretically, these results should correlate with the results of the pull-out tests that were observed to fail by pull out of the fill material. Photograph 4 The test is performed with a guillotine apparatus. Each face shell is sheared off in separate tests to derive the bond shear strength (Photograph 5). The arrows indicate the shearing plate elements. The right plate remains stationary; the left plate drops down and shears the face shell from the core sample. Photograph 5 Page 10 Variables Bedding Mortar: All samples were constructed with mortar mixed according to ASTM C 270, Type S, proportioned by volume. The proportions were one part portland cement to one-half part lime to four and onehalf parts sand by volume (1:0.5:4.5). Mortar Fill: Two variations were used with the Proportions method of ASTM C 270: Mix N: Mix S: Type N mortar mixed by proportions 1:1:6. Type S mortar mixed by proportions 1:0.5:4.5 (same as bedding mortar). These mixes were mixed with no additional water. This is similar to the “slushed” mortar in the Clemson research. The mortar fill was mixed in a gasoline-powered mortar mixer. Slump measurements were taken with a concrete slump cone in accordance with ASTM C14315. The mortar fill was placed into the prisms within 30 minutes of mixing. No retempering was done. Pourable Mortar: Two variations were used with the Proportions method of ASTM C 270. These included: Mix NSL: Mix SSL: Type N mortar mixed by proportions 1:1:6 with water added, producing a slump of 6 inches. Type S mortar mixed by proportions 1:0.5:4.5 with water added, producing a slump of 6 1/4 inches. These mixes had water added to create a pourable consistency. The previous research at NCMA used a 7 to 9 inch slump; the Clemson work used a 10 inch slump. The pourable mortar was mixed in a gasoline-powered mortar mixer. Slump measurements were taken with a concrete slump cone in accordance wtih ASTM C143. The pourable mortar was placed into the prisms within 30 minutes of mixing. Grout: Two variations were used: Mix G: Mix ModG: ASTM C 476 fine grout mixed by proportions 1:0.1:3.3 with a slump of 10 1/4 inches. The proportions are: portland cement, lime, and sand aggregates. ASTM C476 fine grout modified with extra lime to proportions of 1:0.4:4.2 with a slump of 9 ½ inches. Effectively, this is a Type S mortar with a grout slump. Page 11 Mix G is the basis for comparison for the other mixes since grout is currently recommended by codes and standards for commercial construction. However, recognizing that grout usually produces much higher strength than is normally associated with mortars, a modified mix (ModG) was created with increased lime content to produce a mix with a compressive strength close to 2,500 psi, which was anticipated for the Type S mortar mix. Mix ModG does not comply with the proportions method of ASTM C 476 by virtue of its higher lime content but does conform to the strength requirements of that standard. ASTM C 476 specifies a grout slump of between 8 inches and 11 inches. While ASTM allows the grout to be mixed by proportions, MSJC requires the grout have a minimum strength of 2,000 psi. Grout was mixed in a gasoline-powered mortar mixer. Slump measurements were taken with a concrete slump cone in accordance with ASTM C 143. The grout was placed in the prisms within 30 minutes of mixing. Concrete Masonry Units: Two types of 8-inch CMUs were used for the pull-out tests and bond shear tests. Both were manufactured by Zappala Block, Inc., of Rensselaer, New York. One type was a regular (normal weight) CMU meeting ASTM C 9016. The second type of CMU was the same as the first with the exception that Block Plus-W10, a liquid integral water-repellent admixture by Addiment Incorporated, Atlanta, GA, (now a subsidiary of W.R. Grace ) was included in the mix in an attempt to provide a lower water absorption rate. There is no ASTM test to evaluate the rate of absorption in CMU, only total absorption. Thus, it is not possible to quantify the effect of the integral water-repellent on the rate of absorption. The face shells of the units were tapered with the top 1 7/16 inches thick and the bottom 1 1/4 inches thick. The webs were also tapered with the top 1 1/4 inches thick and the bottom 1 1/2 inches thick. Page 12 MATERIAL CHARACTERIZATION Sand Test samples were prepared using natural sand from the sand pit of William M. Larned and Sons in Schenectady, New York. The sand is regularly used locally on masonry projects based upon the ASTM C14417 testing and certification by Construction Technologies Inc. of Schenectady, New York (Appendix A). Sieve analyes were performed on two additional samples by Ryan-Biggs Associates and Chemical Lime Company for conformance with ASTM C 144. Subsequently, the sand tests were compared to ASTM C 40418. All three analyses indicated a fine-grained sand. The test results by Construction Technologies Inc. and Ryan-Biggs Associates indicated the sand met C 144, while the Chemical Lime test indicated it did not. Copies of these analyes are included in Appendix A. The results are not inconsistent. Two sieve tests indicated the samples were at the high end of the range for nearly all sieve sizes. The third test indicated that the material exceeded the high end of the range on two sieve sizes. It is not unreasonable that the one sample would exceed the high end of the range for a specific sieve size for this material. Based upon the performance of the sand in the local market and the two passing tests, conformance with ASTM C 144 and its gradation requirements was assumed. While the mortar fill sand was tested for compliance with ASTM C 144, grout aggregates are required to meet ASTM C 404. By comparing standards, natural sands meeting ASTM C 144 also meet the standards for fine aggregates in accordance with ASTM C 404. Grout Grout prisms were made in accordance with ASTM C 1019 to determine compressive strength. The air temperature was approximately 70°F with a relative humidity of approximately 55 percent at the time of grout mixing and placement. Prisms were kept moist with damp paper towels until block molds were removed after two days. The prisms were then wrapped with damp paper towels and placed in plastic bags, palletized, and transported to the lab by RBA. At the lab, they were placed in a water storage tank in accordance with ASTM C 51119 to finish the curing process. Three samples of each mix were tested at 7, 14, 28, and 90 days. A summary of the results is shown below in Table 1. Individual test results are in Appendix B. All mixes achieved approximately 85 percent of their 28-day strength within 7 days. Between 28 and 90 days, the mixes gained less than10 percent greater strength. Mix G, the typical grout mix, averaged 3,677 psi at 28 days. The modified grout, Mix ModG, averaged 2,323 psi at 28 days. Both mixes had one unusually low test with the 28-day strengths that can not be explained. The table gives values denoted with a * that ignore the low values. These values seem more representative of the actual strength when compared to the 7, 14, and 90 day strengths. At 90 days, the average values (low values) were 4,187 (4,140) and 3,073 (2,940), respectively. Both mixes, G and Mod G, easily surpass the 28-day minimum compressive strength of 2,000 psi recommended in the MSJC. The modified grout mix (Mod G) was originally selected to develop a mix that was a high-slump Page 13 grout with a strength close to 2,500 psi at 28 days. That was achieved. Mix 7 Days 14 Days 28 Days 90 Days 3080 4050 3010 4200 3160 3460 4180 4220 2790 3950 3840 4140 Mean 3010 3820 3677 (*4010) 4187 Std Deviation 195 316 602 34 COV (%) 6.5 8.3 13.3 1.0 2490 2470 2760 3240 2400 2630 1380 3040 2360 2400 2830 2940 Mean 2416 2500 2323 (*2795) 3073 Std Deviation 67 118 818 153 COV (%) 2.8 4.7 35.2 5.0 G ModG Table 1 - Grout Compressive Strengths Mortar Fill and Pourable Mortar Since the mortar fill and pourable mortar are being used as grout, samples were also made in accordance with ASTM C 1019, which is intended for grout and is not the traditional method for testing mortars. The air temperature was approximately 70°F with a relative humidity of approximately 55 percent at the time of mortar fill mixing and placement. Prisms were kept moist with damp paper towels until the block molds were removed after two days. The prisms were then wrapped with damp paper towels and placed in plastic bags, palletized, and transported to the lab by RBA. At the lab, they were placed in a water storage tank in accordance with ASTM C 511 to finish the curing process. Three samples of each mix were tested at 7, 14, 28, and 90 days. A summary of results are shown below in Table 2. Individual tests results are in Appendix B. Page 14 Of the mortar fills, Mix S meets the MSJC minimum compressive strength of 2,000 psi for grout; Mix N does not. Of the pourable mortars, neither Mix NSL nor Mix SSL meets the MSJC minimum compressive strength of 2,000 psi for grout. Mix 7 Days 14 Days 28 Days 90 Days 1190 1450 1550 1460 1240 1460 1220 1360 1320 1320 1530 1620 Mean 1250 1410 1433 1480 Std Deviation 66 78 185 131 COV 5.3 5.5 12.9 8.9 1270 1460 1680 1620 1300 1560 1360 1590 1320 1350 1570 1140 Mean 1297 1457 1537 1450* Std Deviation 25 105 163 269 COV 1.9 7.2 10.6 18.6 2040 2010 2600 2160 2020 2000 2620 2550 2180 2400 2420 2160 Mean 2080 2137 2547 2290* Std Deviation 87 228 110 225 COV 4.2 10.7 4.3 9.8 1780 2010 1690 2230 1800 1720 1890 2250 1690 1940 1820 2140 Mean 1757 1890 1800* 2207 Std Deviation 59 151 101 59 COV (%) 3.4 8.0 5.6 2.7 N (%) NSL (%) S (%) SSL Table 2 - Mortar Fill Compressive Strengths Tested in Accordance with ASTM C 1019 None of the mixes meet the minimum slump requirements of ASTM C 476. The increase in water content going from a mortar consistency to a pourable mixture had little affect Page 15 on the strength of the N mix going to the NSL mix. However, the increase in water content reduced the compressive strength in the SSL mix from the S mix. Individual results did not conform to the usual strength gain trend for Mix NSL at 90 days, Mix S at 90 days, and Mix SSL at 28 days. These could not be explained and either raised or lowered the mean values. These values are noted with a * in Table 2. The mortar used as bedding mortar and mortar fill was also characterized by Chemical Lime Company. The results are part of Appendix A. They provide mortar cube strengths that will be discussed later. Concrete Masonry Units The units were normal weight and manufactured in accordance with ASTM C 90. Manufacturer’s data indicates the average net compressive strength is approximately 3,138 psi based upon ASTM C 14020 testing (Appendix C). Reinforcement Twenty-four-inch lengths of No. 5 reinforcement meeting ASTM A 61521 were used for the pull-out tests. The fabricator reported that the actual yield strength was 61,500 psi and the actual tensile strength was 98,500 psi. For analysis purposes, the yield capacity was based upon 60,000 psi yield strength and 90,000 psi tensile strength consistent with ASTM A 615 minimum requirements. This produces a yield capacity of 18.6 kips and a tensile capacity of 27.9 kips. Compressive Strength of Masonry Using the Unit Strength method, Section 1.4B.2.b., Table 2 of the 2002 MSJC Specifications22, the compressive strength of the masonry was determined based upon Type S mortar in combination with the CMU unit strength of 3,138 psi. This gives a calculated compressive strength of the masonry equal to 2,178 psi. While the grout strength is not included in the development of this value, the MSJC Specification requires that the grout meets either ASTM C 476 or the grout compressive strength equals or exceeds f'm but not less than 2,000 psi. Page 16 For this study, the compressive strength of the masonry ( f'm) was taken conservatively as 2,178 psi or the mortar fill strength, whichever is less, as shown in Table 3. Mix Compressive Strength (psi) from Tables 1 and 2 Assumed f'm (psi) (Compressive Strength of Masonry) Mortar fill N 1,433 1,433 Mortar fill S 2,547 2,178 Pourable mortar NSL 1,537 1,537 Pourable mortar SSL 1,800 1,800 Grout G 4,010 2,178 Grout ModG 2,795 Table 3 - Compressive Strength of Masonry 2,178 Page 17 TESTING RESULTS Pull-Out Tests Loads Complete results are provided in Appendix D. Photographs of the tests are included on a disk that accompanies this report. Figure 3 shows a summary of the test results for the regular CMU with the various mixes. For reference, the yield strength of the reinforcement is plotted. As previously noted, the reinforcement has a minimum yield strength of 18.6 kips and a minimum tensile strength of 27.9 kips. Figure 3 - Pull-Out Loads versus Mix Type for Regular CMU Figure 4 shows the summary of the results for the CMU with water-repellent admixture. Individual test results are in Appendix D. Page 18 Mix G and Mix ModG gave comparable results. Figure 4 - Pull-Out Loads versus Mix Type for Water-Repellent CMU Page 19 Figure 5 superimposes the results for all tests. In all tests, the CMU with water-repellent admixture gave higher results. Figure 5 - Pull-Out Loads versus Mix Type for CMU Page 20 Failure Types Failure mechanisms took several forms. For the purpose of these descriptions, fill material is either mortar fill, pourable mortar, or grout. Failures can be classified as: 1. CMU cracking; fill material cracking (Photograph 6). Photograph 6 2. CMU cracking; little or no fill cracking but slippage of the fill material from the core (Photograph 7). 3. No CMU cracking; reinforcement and Photograph 7 Page 21 spalling around reinforcement slippage (Photograph 8). Photograph 8 Cracking was identified as outwardly visible cracking. In some samples, cracking occurred internal to the fill material. This was evident in those samples where the face shells broke away exposing the fill material and the tensile failure of the fill material near the mortar joint level. Cracking of the CMU is considered a preferred method of failure in that the stress is being transferred to the units. Referring back to Figure 2, it is noticeable that the CMU has tapered face shells. For the fill material to be pulled out of the top of the specimen, it is possible some of the masonry cracking results from the “wedging” action of the fill material as it slips within the tapered core. Had the sample been constructed upside down, the fill material would have been locked into the lip created by the overhanging upper unit at the bed joint. In either configuration, there would have been some mechanical advantage to preventing the fill material from pulling through. Fill material slippage or slippage of the reinforcement is not a preferable mode of failure. Fill material slippage was a dominant mode of failure for Mix N with regular CMU (four tests) and also occurred with Mix SSL (two tests) and Mix ModG (one test). With the water-repellent CMU, Mix N (one test) and Mix S (one test) also had fill slippage. Fill material slippage is a result of bond failure between the fill material and the units. Shrinkage of the fill material reduces the bond to the CMU and increases the possibility of fill material slippage from tension in the reinforcement. Reinforcement slippage, independent of significant cracking, was the dominant mode of failure for Mix NSL with water-repellent CMU (six tests) and also occurred with Mix N with water-repellent CMU (one test). Visible in Photograph 7 is shrinkage at the interface of the CMU and fill material. This may have occurred because the samples were initially air dried before being sent to the lab for moist curing and not covered with a plastic bag as recommended by ASTM C 1019. However, it is more indicative of how real samples are constructed and may perform. Page 22 Bond Tests Six-inch-diameter core samples were taken from the prisms as recommended by the California standard. The cells of the CMU were narrow and did not have sufficient width to take the 6-inch cores without coring a portion of the unit. Photograph 9 shows one of the samples after testing; the embedded portion of the web is visible in the sample. Photograph 9 Twelve prisms were made, one for each fill material type and CMU type. One core was taken from each prism. Each core produced two samples. This resulted in 24 bond shear test samples. Subsequently, two additional tests were taken from the Mix S prism of the water-repellent CMU. Loads Table 5 shown later has a summary of test results. Photographs of tests are provided on the disk. The test results were highly variable. Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions with only two shear values for each type of fill material. Failure Types Failure mechanisms took several forms and can be classified as interface or combined. The specimens exhibiting interface failures sheared at the joint between the fill material and unit. The surface was generally smooth with little mortar fill, pourable mortar, or grout remaining. This was the predominant mode of failure. For the combined failure, the mortar fill, pourable mortar, or grout remained partially intact with the CMU and the shearing went through both the fill material and the interface. There were combined failures observed in 5 of the 24 samples. The initial Mix S samples from the water-repellent CMU tested lower than expected, and a second set of samples was retested. During the retest, one face shell debonded during the coring operation and was conservatively recorded as a zero-capacity sample. Page 23 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS Pull-Out Tests 2002 MSJC - Allowable Stress Method Equation 2-8 of the MSJC gives the development length for the reinforcement, l d = 0.0015dbFs ⋅ This value assumes a minimum grout strength of 2,000 psi. For the No. 5 reinforcing bar, the bar diameter db = 0.625 inches. For the Grade 60 reinforcement with the allowable stress, Fs = 24,000 psi, the calculated ld = 22.5 inches. The test specimens had an actual embedment for the reinforcement of 15.6 inches. This length was selected to try to produce the failure mechanism in the fill material. There is no MSJC procedure within the Allowable Stress method for calculating the capacity of a partially developed reinforcing bar. However, we assumed that there is a linear relationship between embedment length and the stress in the reinforcement. Therefore, using Equation 2-8 with our reduced actual embedment of 15.6 inches, we solved for the reduced allowable stress, fs = 16,640 psi. This results in a reduced allowable force in the bar of 5,159 lbs. A factor of 2.5 is used to obtain an anticipated ultimate load of 12,898 lbs. Figures 7 and 8 replicate the test results shown in Figures 3 and 4 and superimpose the anticipated ultimate loads that were calculated. Mix S, Mix SSL, and the grout mixes achieved the anticipated ultimate load. Mix N in water-repellent CMU achieved the anticipated ultimate load also. Page 24 Figure 7 - Pull-Out Loads versus Mix Type for Regular CMU Page 25 Figure 8 - Pull-Out Loads versus Mix Type for Water-Repellent CMU Page 26 2002 MSJC - Strength Design With the introduction of a Strength Design method in the 2002 edition of the MSJC, a new formula for development length was produced. It includes factors for the size of the reinforcement (( ) and cover over the bars (K). Bar diameter (db) and specified compressive strength (f'm) are also 2 variables. The new formula is l d = 0.13db f y γ / φK f' m . ( = 1.0 for a No. 5 bar. K = clear cover or five bar diameters, whichever is less. In this case, the five bar diameters criteria applies and K = 3.13 inches. The capacity reduction factor, N, equals 0.8. Figure 9 shows the variation in required development length versus masonry strength for the No. 5 bar. The six mixes are superimposed along with the actual embedment length of the sample. Since three mixes (Mix S, Mix G, and Mix ModG) had compressive strengths that exceeded the maximum f'm previously determined by the unit strength method, they are plotted also. However, by the standard, the development length for those three mixes would be based upon the maximum f'm value in the figure. Using the 2002 MSJC - Strength Design criteria, all of the mixes required a development length that exceeds the actual length used in the test samples. Theoretically, the ultimate load capacity of the reinforcement should not have been developed and the failure should have occurred in the fill material. Page 27 Figure 9 - Required Development Length versus Compressive Strength of masonry (f’m) for No. 5 Reinforcement Centered in 8-inch CMU Based Upon MSJC Strength Design Page 28 2005 MSJC Recent developments in the MSJC have again resulted in changes to the development length. The development length is the same for both Allowable Stress and Strength Design. The new formula 2 is l d = 0.13db f y γ / K f' m . For the No. 5 bar used in the test, the variables are the same as used in the 2002 Strength Design. The primary changes are that the capacity reduction factor was dropped and ( was changed to 1.3 for No. 6 and No. 7 bars. Figure 10 shows the variation in the required development length versus specified compressive strength for the No. 5 bar. The six mixes are again superimposed along with the actual embedment length of the sample. As with the 2002 MSJC - Strength Design criteria, the strengths of three mixes (S, ModG, and G) exceeded the maximum f'm previously determined by the unit strength method. While all of the mixes are plotted, the development length for the three mixes (S, ModG, and G) would again be based upon the maximum f'm value in the figure. Therefore, using the 2005 MSJC criteria, all of the mixes required a development length that exceeds the actual length used in the test samples and the ultimate load capacity of the reinforcement should not have been developed. Using the actual strength of Mix G as the criterion, it is conceivable that the ultimate load capacity of the reinforcement could be achieved by pull out. Page 29 Figure 10 -Required Development Length versus Compressive Strength of masonry (f’m) for no. 5 Reinforcement Centered in 8-inch CMU Based upon 2005 MSJC Page 30 CODE SUMMARY For the No. 5 bar, Table 4 indicates the results for the three versions of the MSJC standard. The Length column is the required development length for the specific standard. The Load is in kips and represents the force that would be expected to be developed by the actual embedment. The masonry compressive strengths from Table 3 were used to calculate the development lengths for the 2002 MSJC - Strength Design and 2005 MSJC methods. Mix 2002 MSJC - ASD 2002 MSJC Strength 2005 MSJC Length (inches) Load (kips) Length (inches) Load (kips) Length (inches) Load (kips) Mortar fill N 22.5 12.8 32.0 9.1 25.6 11.3 Mortar fill S 22.5 12.8 26.0 11.2 20.8 14.0 Pourable mortar NSL 22.5 12.8 30.9 9.4 24.7 11.7 Pourable mortar SSL 22.5 12.8 28.6 10.2 22.9 12.7 Grout G 22.5 12.8 26.0 11.2 20.8 14.0 Grout ModG 22.5 12.8 26.0 11.2 20.8 14.0 Table 4 - Development Lengths Figure 11 superimposes the tested pull-out values with the calculated values from the three code criteria. By all criteria, pull-out loads obtained with Mix S, Mix SSL, Mix G, and Mix ModG exceeded the calculated capacities for all three design methods. In addition, the pull-out loads obtained with Mix G and Mix ModG exceeded the yield strength of the reinforcement as well. Mix N with water-repellent units achieved the calculated capacities for the three design methods; Mix NSL did not. Page 31 Figure 11 - Pull-Out Loads versus Mix Types Page 32 Tests of Bond Between Fill Material and CMU These test results are provided in Appendix E and are summarized in Table 5. The Average Bond Shear Stress is calculated from the individual test results on the front and rear face shells. The Effective Pull-out Capacity is calculated from the Average Bond Shear Stress times the surface area of the perimeter of the CMU cell for the sample (358.64 in2). The Tested Pull-out results from Figures 3, 4, and 5 are listed along with the calculated Pull-out Bond Stresses resulting from the pull-out tests. Bond Shear StressFront Shell (psi) Bond Shear Stress Rear Shell (psi) Average Bond Shear Stress (psi) Effective Pull-Out Capacity (lbs) Tested Pull-out (lbs) Pull-out Bond Stress (psi) Mix Masonry Unit N Reg 29.6 37.4 33.5 12,015 12,297 34.3 N WR 28.8 24.9 26.9 9,630 14,257 39.8 S Reg 144.8 105.9 125.4 44,956 15,261 42.6 S WR#1 49.1 63.1 56.1 20,120 16,265 45.4 S WR#2 0 93.1 46.5 16,677 16,265 45.4 NSL Reg 141.7 9.3 75.5 27,078 9,682 27.0 NSL WR 17.9 167.4 92.7 33,228 11,402 31.8 SSL Reg 21.8 197.8 109.8 39,379 14,333 40.0 SSL WR 191.6 70.9 131.3 47,072 15,816 44.1 G Reg 204 105.1 154.6 55,428 21,924 61.1 G WR 206.4 338 272.2 97,623 21,977 61.3 ModG Reg 199.3 24.9 112.1 40,204 20,665 57.6 ModG WR 160.4 88.8 124.6 44,687 19,656 54.8 Table 5 - Bond Shear Tests This testing is not incorporated into ASTM. It is primarily used in California where the recommendation from the Office of the Architect of the State of California is that 100 psi is an acceptable bond shear stress. Overall, the bond shear stress results were highly variable. The bond shear stress for tests exceeded 100 psi for Mix S with regular units and Mix G with Page 33 regular and water-repellent units. Mixes NSL, SSL, and ModG with regular and water-repellent units all had one of the two tests exceed 100 psi. The average bond shear stress of Mix S with regular units and Mixes SSL, G, and Mod G with regular and water-repellent units exceed 100 psi. Two sets of samples were tested for Mix S with water-repellent units (WR) because the results of the first tests appeared to be lower than anticipated. The second test gave one higher result, but the other test from the front face shell debonded during the coring operation. In all cases except for Mix N, the average bond shear stress exceeded the calculated bond stresses from the pull-out tests. That correlated well with the pull-out tests in that most did not fail in bond. That was interesting because most of the samples when viewed from the top appeared to have shrinkage around the perimeter of the fill material. From observations of the pull-out tests, we note that there were fill material pull outs (bond shear failure with the CMU) for individual samples comprised of N Reg, N WR, S WR, SSL Reg, and ModG Reg. Page 34 COMMENTS General 1. Pourable mortar Mix SSL is currently allowed by the International Residential Code. 2. The pull-out tests for Mix S versus Mix SSL indicate that mortar fill performs better than “pourable” mortars with a 6 inch slump. 3. The bond tests for Mix S versus Mix SSL indicate that mortar fill performs better than “pourable” mortars with a 6 inch slump with regular CMU but not the CMU with waterrepellent. 4. In the Clemson tests, “pourable” mortars had higher compressive strengths than the mortar fills. As was seen in Table 3, in this study there was little difference in compressive strength for Mix N as a result of adding water to make it pourable (Mix NSL). In contrast to the Clemson study, this study produced a significant reduction in the compressive strength of Mix S by adding water to create a pourable consistency (Mix SSL). 5. Test results indicate that Mix G performed the best of all mixes. While mortar fill Mix S achieved 64 percent of the grout strength of Mix G, it had 70 percent of the pull-out strength for regular CMU and 74 percent of the pull-out strength for the CMU with water-repellent. 6. Table 6 compares the 28-day strengths of Mix N and Mix S when tested as mortar cubes versus the grout prisms. The results are included in Appendix A from Chemical Lime Company. The mortar cubes tested in accordance with ASTM C 78023 overstate the strength of mortar used as fill material. Mortar (mixed by proportions) Mortar Cubes (ASTM C 780) Grout Prisms (ASTM C 1019) Ratio Type N 2421 psi 1433 psi 0.59 Type S 4132 psi 2547 psi 0.61 Table 6 - 28-Day Compressive Strengths for Type N and Type S Mortars This is not unexpected. ASTM C 780 indicates that mortar samples made as cylinders will test to approximately 85 percent of the values obtained using cubes due to the variation in aspect ratio of the samples. In this study, the prisms tested to approximately 60 percent of the cube samples made in compliance with ASTM C 780. The reduction can generally be explained as a result of the increased water content of the prisms providing lower compressive strengths. Therefore, mortar fill should be evaluated in accordance with ASTM C 1019. 7. The use of sand meeting ASTM C 144 appears to be acceptable for mortar fill. Page 35 Based upon the Pull-out Tests: 1. The mortar fill performed better than the “pourable” mortars with a 6 inch slump that are allowed by residential codes for the conditions tested in this study. 2. The mortar fill mixes achieved higher pull-out values when the CMU contained the waterrepellent admixture. The pull-out strengths of the grout mixes were relatively unchanged by the use of CMU with water-repellent admixture. 3. The pull-out load results increased with increasing compressive strength of the fill material. 4. The compressive strengths of Mix N and Mix NSL were less than 1,600 psi when measured by ASTM C 1019. In general, these mixes did not achieve adequate pull-out values. 5. The pull-out loads achieved with mortar fill Mix S exceeded the required calculated loads for all three design methods in the codes. The compressive strength of the mix exceeded 2,000 psi and was closer to 2,500 psi. 6. The pull-out loads achieved with pourable mortar Mix SSL exceeded the required calculated loads for all three design methods. The compressive strength of the mix was approximately 1,800 psi. 7. The pull-out loads achieved with grout mixes Mix G and Mix ModG exceeded the required calculated loads for all three design methods. The compressive strength of the mixes exceeded 2,800 psi. 8. The pull-out loads achieved with the grout mixes (Mix G and Mix ModG) exceeded the yield strength of the reinforcement. This was well beyond what was anticipated or required based upon the three MSJC design methods. All three methods had calculated pull-out loads well below the yield value. 9. The use of water-repellent admixture in the CMU had little affect on the pull-out test results for the grout mixes. It appears the grout water content was sufficiently high that the difference in loss of water through absorption into the units had a negligible effect. 10. While Type M mortar fill was not tested, it is likely that, based upon the results for mortar fill Mix S, it too would have produced pull-out loads that exceed the three design methods. 11. The 2002 and 2005 MSJC formulas produced results for development length that are more conservative when based upon the compressive strength of the masonry (f'm) as determined by the unit strength method rather than the fill material strength. 12. Pull-out strengths for Mix S and Mix SSL were acceptable in spite of the observed shrinkage of the fill material. Based upon the Bond Tests: Page 36 1. The coring operation to obtain the bond shear samples is highly operator dependent. Based upon the speed of the coring, the angle of the core relative to the surface, and the quality of the core drill, it is possible to introduce stress into the sample and, in the extreme case, to “spin-off” the face shell. The reduction in the tested shear stress due to the sampling is unknown. Standard procedure is to take a second sample if one is damaged by the coring operation. 2. The fill material exhibited shrinkage, but the mortar fill shrinkage seemed greater. The shrinkage and the coring operation apparently resulted in significant shear stress differences from one face shell to the other in samples Mix NSL, Mix SSL, Mix G, and Mix ModG with regular CMU and Mix NSL, Mix S, Mix SSL, Mix G, and Mix ModG with waterrepellent units. 3. While the California standard does not have a minimum standard for its grout bond test, 100 psi is considered acceptable. The grout mixes developed the highest bond shear stresses. The other mixes did not give consistent results. 4. The effect of coring a portion of the web of the CMU was considered insignificant. The results were not consistently greater due to a portion of the unit in the sample. 5. With only two bond shear tests for each mix, there was too much variability in the results to draw any reliable conclusions about the shear bond characteristics of the fill materials. Page 37 CONCLUSIONS/RECOMMENDATIONS Overall, the goals of the research were achieved. Mortar fill was evaluated to compare it with pourable mortar and grout as a means to encase reinforcement in vertical applications. The results are: 1. The elemental test results indicate that mortar fill could be an acceptable alternative to fine grout for modified low-lift applications of reinforced masonry. The specifics of the modifications for installation techniques need to be developed but could include the lift height, the method of consolidating the mortar fill, the board life of the mortar, retempering, and splicing the reinforcement. 2. While high-slump grout may be necessary for high-lift grouting operations, the high-slump material may not be required for low-lift grouting applications. Type S and Type M mortar fill and “pourable” mortars offer an alternative worth further consideration. Mix N and Mix NSL did not perform adequately. It appears the compressive strength of the material is too low for use as a fill material. The minimum MSJC value of 2,000 psi for the grout seems reasonable. 3. Mortar fill performed better than “pourable” mortar in the pull-out tests. 4. The development length of reinforcement based upon the MSJC criteria (2002-Strength Design and 2005) should be based upon the lesser of the compressive strength of the masonry (from unit strength method or prism test method) or the 28-day mortar fill strength. The minimum mortar fill strength should be 2,000 psi. 5. A reduction in the absorption of the concrete masonry units improved the pull-out strength of the mortar fill. Lower absorption of the units was created by the use of an integral waterrepellent additive. The improved strength is likely due to the higher compressive strength of the fill due to reduced water loss from the mix. Whereas the grout has excess water to release to the units, the water retention from the mortar fill is helpful in the hydration of the mortar. It could also be due to reduced shrinkage. This is somewhat consistent with Isberner’s statements that low slump material can provide adequate strengths. However, the mix needs to be appropriately designed. 6. No definite conclusions can be drawn from the grout bond shear stress tests based upon the variability of the results and the small sampling. 7. The sampling process for the bond shear stress test weakens the sample. The results seem to be affected by the sampling. A test program that compares the bond shear test method to push-through samples of fill material might provide some insight into the effects of the coring operation. Page 38 8. Full-scale wall tests that evaluate flexural and axial capacity should be performed based upon the following criteria. A. B. C. D. E. 9. Mortar fill with a minimum compressive strength of 2,000 psi when tested in accordance with ASTM C 1019. This should be Type S and Type M mortars. For consistency with this study, the mortar fill would be portland cement and limebased mortar meeting ASTM C 270. Wall specimens should be constructed in a modified low-lift application. A procedure should be developed for the installation that should be considered mandatory if the use of mortar as grout is proposed to MSJC. The procedure should include lift height, consolidation method, board life of the mortar, retempering, and reinforcement splicing. Consolidation of the mortar fill must be complete and consistent. The results should be compared to those for walls constructed using the low-lift method using fine grout. The bond shear strength tests should be repeated with a larger sampling to further examine the shrinkage characteristics of the mortar fill and its impact on bond shear stress. Several additional issues became evident during this research and should be evaluated further. A. B. C. D. E. The performance of the ModG mix indicates that Type S and Type M portland cement and lime mortars mixed to a grout consistency could provide a suitable substitute for ASTM C 476 grout. The unit strength method for determining the compressive strength of the masonry is based upon the CMU strength and the mortar type. It does not involve the mortar fill or grout strength. This study indicates that the development length and lap lengths for reinforcement should be evaluated using the mortar fill or grout strength. In this study, the reinforcement always developed in a shorter length than calculated using the compressive strength of the masonry based upon the unit strength method. One distinct possibility is that the unit strength underestimates the compressive strength of the masonry sufficiently to require significantly longer laps than would be necessary had the compressive strength of the masonry been determined using the prism test method. MSJC should reconsider the lap lengths and development lengths for reinforcement. To avoid overly conservative lap lengths, the compressive strength of the masonry used in the determination of lap lengths should not be based upon the unit strength method; it should be based upon grouted prisms. It is the author’s opinion that research on lap lengths is needed that tests samples in flexure in comparison to pure tension samples. It would be appropriate to determine different lap lengths based upon the application. Shrinkage effects of mortar fill and grout should be evaluated further relative to bond with regular and low absorption units. Grout aids or other admixtures could be considered that increase bond. Page 39 F. G. The use of water-repellent additives or other admixtures in mortar fill should be evaluated for their affect on the material when used as a grout. The importance of the bond shear strength should be evaluated in light of the existence of core insulation that has received the acceptance of BOCA Evaluation Services for grouted masonry. The insulation is U-shaped and debonds the grout from the face shells and one web leaving the grout only bonded to one web. Page 40 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Peer Review Group The peer review team for the research program: John Buck , Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers Local 2. Brian Trimble PE, Brick Industry Association (formerly International Masonry Institute - MidAtlantic Region). Gene Abbate, International Masonry Institute - Empire State Office. Diane Throop PE, Consultant; Chair of MSJC Construction Practices Subcommitee. Robert Thomas, National Concrete Masonry Association. Margaret Thomson, Chemical Lime Co.; MSJC member. Dr. Arturo Schultz, University of Minnesota; MSJC member. Tom Murray, Colonie Masonry Corporation of Albany, Inc. Arthur Del Savio, Del Savio Construction Corp. Donations Major funding for this research was provided by: International Masonry Institute, represented by Mr. Gene Abbate. National Lime Association, represented by Mr. Eric Males and Ms. Margaret Thomson. Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers, Local No.1, New York, New York. National Concrete Masonry Association Research and Education Foundation represented by Mr. Robert Thomas, P.E., Vice President of Engineering. Donated materials and services were provided by: Dimension Fabricators, Scotia, New York, represented by Mr. Scott Stevens, President reinforcement. V. Zappala and Co., Rensselaer, New York, represented by Ralph Viloa Jr. - concrete masonry units. Glens Falls Lehigh Cement Co., Glens Falls, New York, represented by Mr. Peter Maloney portland cement. Graymont Dolime (OH), Inc., Genoa, Ohio, - hydrated lime. Chemical Lime Co., Henderson, Nevada, - mortar characterization represented by Ms. Margaret Thomson and Mr. Richard Godbey. Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers - Local No. 2, Albany, New York, represented by Mr. John Buck and Mr. Bart McClellan - masonry sand; fabrication of samples. Subcontractors Page 41 Evergreen Testing and Environmental Services, Inc., Menands, New York, - compression testing. Materials Characterization Laboratory Inc., Scotia, New York, - pull-out tests. National Concrete Masonry Association, Herndon, VA - grout bond shear tests. Ryan-Biggs Associates, P.C. Thanks to Don Trojak for coordinating the testing and assisting with the sample preparation; Ross Shepherd for graphics; Jill Shorter for report preparation assistance; Jack Healy for reviewing the report; and Barbara Meagher for editing. Page 42 APPENDIX A - SAND TEST RESULTS RYAN-BIGGS ASSOCIATES, P.C. MATERIAL SOURCE: Mason Sand from Wm. Larned & Sons Inc. MATERIAL DESCRIPTION: Sand, fine/medium, trace Silt/Clay MATERIALPROJECT USE: Mortar and Mortar Fill RBA Project Number: 8379 DATE: October 15, 2004 Sieve Percent Size Retained #4 0 #8 0 #16 4 #30 27 #50 67 #100 86 #200 96 C-144 C-144 Percent Low High Passing 100 100 95 100 100 70 100 96 40 75 73 10 35 33 2 15 14 0 5 4 100 C-144 Low 80 60 C-144 High 40 Percent Passing 20 #5 0 #1 00 #2 00 #3 0 #1 6 #8 0 #4 Percent Passing ASTM C144: Size Distribution of Sand: Sieve Analysis Sieve Sizes A-1 A-2 A-3 A-4 A-5 A-6 APPENDIX B - GROUT AND MORTAR FILL TEST RESULTS B-1 B-2 B-3 B-4 APPENDIX C - CONCRETE MASONRY UNIT TEST RESULTS C-1 APPENDIX D - PULL-OUT TEST RESULTS D-1 D-2 D-3 D-4 D-5 D-6 APPENDIX E - BOND TEST RESULTS E-1 APPENDIX F - REFERENCES 1. Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures (ACI 530-02 / ASCE 5-02 / TMS 40202), Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2002. 2. ASTM C 476-02, “Standard Specification for Grout for Masonry,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 3. ASTM C 270-02, “Standard Specification for Mortar for Unit Masonry,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 4. 2005 Personal correspondence from James E. Amrhein, former Executive Director of Masonry Institute of America, Los Angeles, CA 5. Grout...The Third Ingredient, James E. Amrhein, MASONRY INDUSTRY magazine, June 1980 6. Technical Note 9B - Manufacturing, Classification, and Selection of Brick, Part 3 Revised December 2003, Brick Industry Association, Reston, VA 7. Grout for Reinforced Masonry, A.W. Isberner, Jr., ASTM STP: Masonry: Materials, Properties, and Performance, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA., 1982 8. 1982 Edition, Uniform Building Code, International Code Council, Falls Church, VA. 9. One and Two-Family Dwelling Code, Council for American Building Officials, International Code Council, Falls Church, VA. 10. 2000 International Residential Code, International Code Council, Falls Church, VA, 2000. 11. Reinforcement Bond Strengths in Portland Cement-Lime Mortars, Masonry Cement Mortars, and Fine Grout, NCMA research and Development Laboratory, Hedstrom and Thomas, June 1991. 12. Feasibility of Using Mortar in Lieu of Grout for Reinforced Hollow Clay Wall Construction, Russell Brown, Clemson University, 1998. Unpublished, but cited with permission of the Wall Committee of the National Brick Research Center. 13. Bond Tests Between Steel and Mortar in Reinforced Brick Masonry, F.E. Richart, Structural Clay Products Institute, February, 1949. 14. ASTM C 1019-02, “Standard Test Method for Sampling and Testing Grout,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 15. ASTM C 143-03, “Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic Cement Concrete,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 16. ASTM C 90-02, “Standard Specification for Loadbearing Concrete Masonry Units,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. F-1 17. ASTM C 144-02, “Standard Specification for Aggregate for Masonry Mortar,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 18. ASTM C 404-97, “Standard Specification for Aggregates for Masonry Grout,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 19. ASTM C 511-03, “Standard Specification for Mixing Rooms, Moist Cabinets, Moist Rooms, and Water Storage Tanks Used in the Testing of Hydraulic Cements and Concretes,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 20. ASTM C 140-02a, “Standard Test Methods for Sampling and Testing Concrete Masonry Units and Related Units,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 21. ASTM A 615, “Standard Specification for Deformed and Plain Billet-Steel Bars for Concrete Reinforcement,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 22. Specifications for Masonry Structures (ACI 530.1-02 / ASCE 6-02 / TMS 602-02), Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2002. 23. ASTM C 780-02, “Standard Test Method for Preconstruction and Construction Evaluation of Mortars for Plain and Reinforced Unit Masonry,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. F-2