CALIFORNIA 4-HOUR

ANNUITY TRAINING COURSE

HOW FIXED, VARIABLE AND INDEX ANNUITY

CONTRACT PROVISIONS

AFFECT CONSUMERS

(2015 EDITION)

Researched and Written by:

Edward J. Barrett

CFP , ChFC , CLU, CEBS, RPA, CRPS, CRPC

Disclaimer

This course is designed as an educational program for financial advisors and insurance

professionals. EJB Financial Press is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional

advice and the reader should consult legal counsel as appropriate.

We have tried to provide you with the most accurate and useful information possible.

However, one thing is certain and that is change. The content of this publication may be

affected by changes in law and in industry practice, and as a result, information contained

in this publication may become outdated. This material should in no way be used as an

original source of authority on legal and/or tax matters.

Laws and regulations cited in this publication have been edited and summarized for the

sake of clarity.

Names used in this publication are fictional and have no relationship to any person living

or dead.

This presentation is for educational purposes only. The information contained within this

presentation is for internal use only and is not intended for you to discuss or share with

clients or prospects. Financial advisors are reminded that they cannot provide clients with

tax advice and should have clients consult their tax advisor before making tax-related

investment decisions.

EJB Financial Press, Inc.

7137 Congress St.

New Port Richey, FL 34653

(800) 345-5669

www.EJBfinpress.com

This book is manufactured in the United States of America

© 2015 EJB Financial Press Inc., Printed in U.S.A. All rights reserved

2

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Edward J. Barrett CFP®, ChFC®, CLU, CEBS®, RPA, CRPS, CRPC®, began his

career in the financial and insurance services back in 1978 with IDS Financial Services,

becoming a leading financial advisor and top district sales manager in Boston,

Massachusetts. In 1986, Mr. Barrett joined Merrill Lynch in Boston as an estate and

business-planning specialist working with over 400 financial advisors and their clients

throughout the New England region assisting in the sale of insurance products.

In 1992, after leaving Merrill Lynch and moving to Florida, Mr. Barrett founded The

Barrett Companies Inc., Broker Educational Sales & Training Inc., Wealth Preservation

Planning Associates and The Life Settlement Advisory Group Inc.

Mr. Barrett is a qualifying member of the Million Dollar Round Table, Qualifying

Member Court of the Table® and Top of the Table® producer. He holds the Certified

Financial Planner designation CFP®, Chartered Financial Consultant (ChFC), Chartered

Life Underwriter (CLU), Certified Employee Benefit Specialist (CEBS), Retirement

Planning Associate (RPA), Chartered Retirement Planning Counselor (CRPC) and the

Chartered Retirement Plans Specialist (CRPS).

About EJB Financial Press

EJB Financial Press, Inc. (www.ejbfinpress.com) was founded in 2004, by Mr. Barrett to

provide advanced educational and training manuals approved for correspondence

continuing education credits for insurance agents, financial advisors, accountants and

attorneys throughout the country.

About Broker Educational Sales & Training Inc.

Broker Educational Sales & Training Inc. (BEST) is a nationally approved provider of

continuing education and advanced training programs to the mutual fund, insurance and

financial services industry.

For more information visit our website at: www.bestonlinecourses.com or call us at 800345-5669.

3

This page left blank intentionally

4

BACKGROUND

Section 1749.8 of the California Insurance Code which took effect on January 1, 2005,

pursuant to subdivision (a) it requires that California resident and non-resident life agents

who sell annuity products must first complete eight (8) hours of annuity training that is

approved by the California Department of Insurance (CDI). In addition, pursuant to

subdivision (b), the law also requires life agents who sell annuity products to

satisfactorily complete an additional four hours of annuity training every two years prior

to their license renewal. For resident agents, this requirement is part of, and not in

addition to, their continuing education requirements.

On September 20, 2011, the governor signed into law, Assembly Bill (AB) 689 (Chapter

295, Statutes of 2011), an act to add Article 9 (commencing with Section 10509.910) to

Chapter 5 of Part 2 of Division 2 of the Insurance Code, relating to annuity transaction.

This act became effective January 2, 2012. AB 689 adds Section 10509.915(a) to the

California Insurance Code which states that an insurance producer shall not solicit the

sale of an annuity product unless the insurance producer has adequate knowledge of the

product to recommend the annuity and the insurance producer is in compliance with the

insurer’s standards for product training. Insurance producers may rely on insurerprovided product-specific training standards and materials to comply with the productspecific training requirement. Please note that AB 689 does not change the annuity

training requirements which are stated above in Section 1749.8 (a)(b) of the

California Insurance Code.

To assist California resident and non-resident agents meet Section 1749.8 (b), the fourhour ongoing annuity training requirement, this course has been filed an approved by the

California Department of Insurance (CDI). To receive continuing education credit for

this course you must complete either a paper exam or an online exam with a total of 50

questions and receive a passing grade of 70% or higher.

Disclaimer - The California Department of Insurance is released of responsibility for

approved course materials that may have a copyright infringement. In addition, no course

approved for either pre-licensing or continuing education hours or any designation

resulting from completion of such courses should be construed to be endorsed by the

Commissioner.

5

This page left blank intentionally

6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR .................................................................................................. 3 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 13 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 13 Learning Objectives .......................................................................................................... 13 Annuity Defined................................................................................................................ 13 History of Annuities .......................................................................................................... 14 Annuities in the U.S ...................................................................................................... 15 U.S. Individual Annuity Sales ...................................................................................... 16 Annuity Buyers ................................................................................................................. 17 Primary Uses of Annuities ................................................................................................ 17 Annuity Outlook ............................................................................................................... 18 Chapter 1 Review Questions ........................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 2 CLASSIFICATION OF ANNUITIES ................................................ 21 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 21 Learning Objectives .......................................................................................................... 21 Classification of Annuities................................................................................................ 21 Purchase Option ................................................................................................................ 22 Single Premium ............................................................................................................. 22 Periodic (Flexible) Payment ......................................................................................... 22 Date Benefit Payments Begin ........................................................................................... 22 Deferred Annuities ........................................................................................................ 23 Immediate Annuities ..................................................................................................... 24 Deferred Income Annuity ............................................................................................. 25 Investment Options ........................................................................................................... 26 Fixed Annuity ............................................................................................................... 26 Variable Annuity ........................................................................................................... 26 Sales of Annuities ......................................................................................................... 27 Payout Options .................................................................................................................. 27 Chapter 2 Review Questions ........................................................................................... 30 CHAPTER 3 FIXED ANNUITIES ........................................................................... 31 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 31 Learning Objectives .......................................................................................................... 31 Advantages of Fixed Annuities......................................................................................... 31 Disadvantages of Fixed Annuities .................................................................................... 32 Fixed Annuity Fees and Expenses .................................................................................... 32 Contract Charge ............................................................................................................ 32 Interest Spread .............................................................................................................. 32 Surrender Charges ......................................................................................................... 32 Fixed Annuity Sales .......................................................................................................... 33 Types of Fixed Annuities .................................................................................................. 33 Crediting Rates of Interest ................................................................................................ 34 Non-forfeiture Interest Rate .......................................................................................... 35 7

Current Rate of Interest ................................................................................................. 35 Portfolio Rate ................................................................................................................ 35 New Money Rate .......................................................................................................... 36 Calculating the Rate ...................................................................................................... 37 Interest Rate Trends ...................................................................................................... 38 Interest Rate Projections ............................................................................................... 38 Bonus Annuities ............................................................................................................ 38 Two-Tiered Annuities ................................................................................................... 39 Fixed Annuitization: Calculating Fixed Annuity Payments ............................................ 39 Chapter 3 Review Questions ........................................................................................... 40 CHAPTER 4 VARIABLE ANNUITIES................................................................... 41 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 41 Learning Objectives .......................................................................................................... 41 VA Defined ....................................................................................................................... 42 The VA Market ............................................................................................................. 42 VA Product Features ..................................................................................................... 44 Separate Accounts ............................................................................................................. 44 Investment Options ....................................................................................................... 44 Accumulation Units ...................................................................................................... 45 VA Charges and Fees........................................................................................................ 46 Mortality and Expense (M&E) Charge ......................................................................... 47 Management (Fund Expense) Fees ............................................................................... 47 Contract (Account) Maintenance Fees.......................................................................... 48 Summary of Above Fees ............................................................................................... 48 Surrender Fees .............................................................................................................. 49 VA Sales Charges ......................................................................................................... 49 Premium Tax ..................................................................................................................... 50 Investment Features .......................................................................................................... 51 Dollar Cost Averaging .................................................................................................. 51 Enhanced Dollar Cost Averaging ................................................................................. 52 Fund Transfers .............................................................................................................. 52 Asset Allocation ............................................................................................................ 53 Asset Rebalancing ......................................................................................................... 53 Guaranteed Minimum Death Benefit ................................................................................ 53 Enhanced GMDB Features ........................................................................................... 54 Initial Purchase Payment with Interest or Rising Floor ................................................ 54 Contract Anniversary, Or “Ratchet” ............................................................................. 55 Reset Option.................................................................................................................. 55 Enhanced Earnings Benefits ......................................................................................... 55 Guaranteed Living Benefit (GLB) Riders......................................................................... 55 Types of GLB Riders .................................................................................................... 56 Guaranteed Minimum Income Benefit (GMIB) ............................................................... 56 GMIB Features and Benefits ........................................................................................ 56 GMIB Caveats .............................................................................................................. 57 GMIB Client Suitability................................................................................................ 58 Guaranteed Minimum Account Balance (GMAB) ........................................................... 58 8

GMAB Example ........................................................................................................... 58 GMAB Caveats ............................................................................................................. 58 GMAB Client Suitability .............................................................................................. 59 Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB) ...................................................... 59 GMWB Example .......................................................................................................... 59 GMWB Caveats ............................................................................................................ 59 GMWB Client Suitability ............................................................................................. 60 Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit for Lifetime .................................................. 60 GMWBL Features and Benefits.................................................................................... 61 GMWBL Client Suitability ........................................................................................... 61 Treatment of Withdrawals from GLB Riders ................................................................... 62 Dollar-for-Dollar ........................................................................................................... 62 Pro-Rata ........................................................................................................................ 62 Variable Annuitization: Calculating Variable Annuity Income Payouts ......................... 63 Annuity Units ................................................................................................................ 63 Assumed Interest Rate (AIR) ........................................................................................ 64 VA Regulation under the Federal Securities Laws ........................................................... 65 Securities Act of 1933 ................................................................................................... 65 Securities Act of 1934 ................................................................................................... 66 Investment Company Act of 1940 ................................................................................ 67 Regulation of Fees and Charges ................................................................................... 67 Outlook for Variable Annuities ........................................................................................ 67 Chapter 4 Review Questions ........................................................................................... 69 CHAPTER 5 INDEX ANNUITIES ........................................................................... 71 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 71 Learning Objectives .......................................................................................................... 71 Index Annuity Defined ..................................................................................................... 71 Index Annuity Market ....................................................................................................... 72 Profile of an IA Buyer....................................................................................................... 72 IA Basic Terms and Provisions......................................................................................... 73 Tied Index ..................................................................................................................... 73 Index (Term) Period ...................................................................................................... 74 Participation Rate .......................................................................................................... 74 Spreads or Margins ....................................................................................................... 75 Cap Rate ........................................................................................................................ 76 No-Loss Provision ........................................................................................................ 77 Guaranteed Minimum Account Value .......................................................................... 77 Liquidity ........................................................................................................................ 77 Fees and Expenses ........................................................................................................ 78 Surrender Charges ......................................................................................................... 78 Interest Calculation ....................................................................................................... 79 Exclusion of Dividends ................................................................................................. 79 Index-Linked Interest Crediting Methods ......................................................................... 79 Annual Reset (Ratchet) Method.................................................................................... 79 High-Water Mark Method ............................................................................................ 81 Point-to-Point Method .................................................................................................. 81 9

Interest Crediting Method Comparison ........................................................................ 84 Averaging ...................................................................................................................... 85 Other Interest Crediting Methods ..................................................................................... 85 Multiple (Blended) Indices ........................................................................................... 85 Monthly Cap (Monthly Point-to-Point) ........................................................................ 85 Binary, Non-Negative (Trigger) Annual Reset ............................................................. 86 Bond-Linked Interest with Base ................................................................................... 86 Hurdle ........................................................................................................................... 86 Annual Fixed Rate with Equity Component ................................................................. 86 Rainbow Method ........................................................................................................... 87 Index Annuity Waivers and Riders ................................................................................... 88 Types of Riders ............................................................................................................. 89 IA’s with Bonuses ............................................................................................................. 89 Regulation of IA’s............................................................................................................. 90 FINRA Investor Alerts .................................................................................................. 91 Chapter 5 Review Questions ........................................................................................... 92 CHAPTER 6 ANNUITY CONTRACT STRUCTURE ........................................... 93 Overview ........................................................................................................................... 93 Learning Objectives .......................................................................................................... 93 Background ....................................................................................................................... 93 Structuring the Contract .................................................................................................... 94 Annuity Contract Forms ................................................................................................... 94 Owner-Driven ............................................................................................................... 95 Annuitant-Driven Contract ........................................................................................... 95 Parties to the Annuity Contract ......................................................................................... 95 The Owner ........................................................................................................................ 95 Rights of the Owner ...................................................................................................... 96 Changing the Annuitant ................................................................................................ 96 Duration of Ownership ................................................................................................. 96 Purchaser, Others as Owner .......................................................................................... 97 Taxation of Owner ........................................................................................................ 97 Death of Owner: Required Distribution ....................................................................... 97 Spousal Exception ......................................................................................................... 98 The Annuitant ................................................................................................................... 98 A Natural Person ........................................................................................................... 98 Role of the Annuitant .................................................................................................... 98 Naming Joint Annuitants/Co-Annuitants...................................................................... 98 Taxation of Annuitant ................................................................................................... 99 Death of Annuitant ........................................................................................................ 99 The Beneficiary ............................................................................................................... 100 Death Benefit .............................................................................................................. 100 Whose Death Triggers the Death Benefit ................................................................... 100 Changing the Beneficiary ........................................................................................... 101 Designated Beneficiary ............................................................................................... 101 Spouse or Children as Beneficiaries ........................................................................... 101 Non-Natural Person as Beneficiary ............................................................................ 101 10

Multiple Beneficiaries................................................................................................. 101 Taxation of Beneficiary .............................................................................................. 101 Death of Beneficiary ................................................................................................... 102 Maximum Ages for Benefits to Begin ............................................................................ 103 Chapter 6 Review Questions ......................................................................................... 104 CHAPTER 7 SUITABILITY OF ANNUITIES ..................................................... 105 Learning Objectives ........................................................................................................ 105 Licensing and Training Requirements ............................................................................ 105 CIC 1749.8 .................................................................................................................. 106 California Suitability Law............................................................................................... 106 CIC § 10509.910 ......................................................................................................... 106 CIC § 10509.911 ......................................................................................................... 107 CIC § 10509.912 ......................................................................................................... 107 CIC § 10509.914 ......................................................................................................... 107 CIC § 10509.914(i) ..................................................................................................... 108 CIC § 10509.914(e) .................................................................................................... 109 CIC § 10509.914(f)(D)(E) .......................................................................................... 109 CIC § 10509.916 ......................................................................................................... 110 CIC § 10509.917 ......................................................................................................... 110 CIC § 10509.918 ......................................................................................................... 111 The Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 .................................... 111 Chapter 7 Review Questions .......................................................................................... 113 CHAPTER 8 CIC CONTRACT PROVISIONS, RIDERS AND PENALTIES . 115 Overview ......................................................................................................................... 115 Learning Objectives ........................................................................................................ 115 CIC Contract Provisions ................................................................................................. 115 CIC §10540 ................................................................................................................. 116 CIC § 10127.10 ........................................................................................................... 116 CIC § 10127.12 ........................................................................................................... 116 CIC § 10127.13 ........................................................................................................... 117 Surrender Charge Waivers .............................................................................................. 117 Nursing Home ............................................................................................................. 118 Terminal Illness .......................................................................................................... 118 Unemployment ............................................................................................................ 118 Disability ..................................................................................................................... 118 Death ........................................................................................................................... 118 Charges and Fees ........................................................................................................ 118 Required Notice and Printing Requirements .............................................................. 118 Withdrawal Privilege Options..................................................................................... 119 Market Value Adjustment ............................................................................................... 119 Policy Administration Charges and Fees ........................................................................ 120 Life Insurance and Annuity Contract Riders .................................................................. 120 Long-Term Care Benefits Rider ..................................................................................... 120 Terms of Riders........................................................................................................... 120 Difference between Crisis Waivers & Long-Term Care Riders ................................. 120 Skilled Nursing Facility Rider .................................................................................... 121 11

Hospice Rider.............................................................................................................. 121 CIC Penalty Statutes ....................................................................................................... 121 CIC Section 780 .......................................................................................................... 121 CIC Section 781 .......................................................................................................... 122 CIC Section 782 .......................................................................................................... 122 CIC § 786 .................................................................................................................... 122 CIC § 789.3 ................................................................................................................. 123 CIC § 1738.5 ............................................................................................................... 123 CIC § 10509.9 ............................................................................................................. 124 CIC § 10509.916 ......................................................................................................... 124 Chapter 8 Review Questions .......................................................................................... 125 APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................... 127 APPENDIX B ................................................................................................................ 147 CHAPTER REVIEW ANSWERS............................................................................... 149 CONFIDENTIAL FEEDBACK .................................................................................. 151 12

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Overview

Many financial professionals think of the annuity as a modern day investment. However,

annuities were in use long before the Internal Revenue Code was enacted. The creation

of annuities was not tax driven; it was driven by our need for security in an uncertain

world. It was, and is, driven by our need for the insurance features that the annuity

contract provides. The principal insurance role of annuities is to indemnify individuals

against the risk of outliving their resources.

In this chapter, we will define the annuity and review the historical uses of the annuity.

In addition, we will examine the role of annuities in the U.S., their sales, who purchases

the annuity and the reasons for the purchase of an annuity. At the end of the chapter, we

will examine the future outlook for annuities.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Identify how an annuity is defined;

Demonstrate the mathematical concept of an annuity

Explain how annuities have been used throughout history;

Explain the reasons why people purchase annuities today; and

Understand the outlook for the future of annuities.

Annuity Defined

In general terms, an annuity is a mathematical concept that is quite simple in its most

basic application. Start with a lump sum of money, pay it out in equal installments over a

period of time until the original fund is exhausted, and you have an annuity. Expressed

differently, an annuity is simply a vehicle for liquidating a sum of money.

But of course, in practice, the concept is a lot more complex. An important factor

missing from above is interest. The sum of money that has not yet been paid out is

earning interest, and that interest is also passed on to the income recipient (the

“annuitant”).

13

Anyone can provide an annuity as long as they can calculate the payment based upon

three factors:

A sum of money

Length of payout period, and

An assumed interest rate

However, there is one important element absent from this simple definition of an annuity,

and it is the one distinguishing factor that separates insurance companies from all other

financial institutions. While anyone can set up an annuity and pay income for a stated

period of time, only an insurance company can do so and guarantee income for the life of

the annuitant.

The insurance companies, with their unique experience with mortality tables, are able to

provide an extra factor into the standard annuity calculation, a survivorship factor. The

survivorship factor provides insurers with the means to guarantee annuity payments for

life, regardless of how long that life lasts.

Don’t get confused between an annuity and a life insurance contract. Annuities are not

life insurance contracts. Even though it can be said that an annuity is a mirror image of a

life insurance contract—they look alike but are actually exact opposites. Life insurance

is concerned with how soon one will die; life annuities are concerned with how long one

will live.

But did you know that annuities existed long before the existing of insurance companies.

As you will see, annuities have a long and illustrious history going back thousands of

years. In fact, annuities can actually trace their origins back to Roman times.

History of Annuities

There is some evidence that shows that one of the first life annuity ever purchased (or

invested), would have been around 1700 BCE. According to research by Moshe

Molevsky, he uncovered evidence that a life annuity was purchased by a prince ruling the

region of Sint in the Middle Kingdom (1100-1700 BCE). The annuitant’s name was

Price Hepdefal, but little else is known about the annuity itself, in what units it was paid

for and whether it ended up being a good investment for him.

Around the sixth century BCE, within the Old Testament, 2 Kings 25:30 makes reference

to the (life) annuity that was granted to Jehoiakim, king of Judah, by the king of Babylon

upon on his release from prison. By the second and third centuries CE, life annuities

became quite popular in Rome, where mutual aid societies of the Roman legions granted

them to soldiers who retired from military service at age 46. In addition, it has been

reported that during that time ancient Roman contracts known as annua (or “annual

stipends”) promised an individual a stream of payments for a fixed term, or possibly for

life, in return for an up-front payment. Such contracts were apparently offered by

14

speculators who dealt in marine and other lines of insurance. A Roman, Domitius

Ulpianus, compiled the first recorded life table for the purpose of computing the estate

value of annuities that a decedent might have purchased on the lives of his survivors.

During the 17th century, governments in several nations, including England and Holland,

sold annuities in lieu of government bonds, to pay for massive, on-going battles with

neighboring countries. The governments received capital in return for a promise of

lifetime payouts to the annuitants. The governments would then create a “tontine”,

promising to pay for an extended period of time if citizens would purchase shares today.

The United Kingdom, locked in many wars with France, started one of the first group

annuity contracts called the State of Tontine of 1693. Participants in these early

government annuities would purchase a share of the Tontine for ₤100 from the UK

Government. In return, the owner of the share received an annuity during the lifetime of

their nominated person (often a child). As each nominee died, the annuity for the

remaining proprietors gradually became larger and larger. This growth and division of

wealth would continue until there were no nominees left. Proprietors could assign their

annuities to other parties by deed or will, or they passed on at death to the next of kin.

Annuities in the U.S

In the United States, annuities made their first mark in America during the 18th century.

In 1759, Pennsylvania chartered the Corporation for the Relief of Poor and Distressed

Presbyterian Ministers and Distressed Widows and Children of Ministers. It provided

survivorship annuities for the families of ministers. Ministers would contribute to the

fund, in exchange for lifetime payments. In Philadelphia in 1812, the Pennsylvania

Company for Insurance on Lives and Granting Annuities was founded. It offered life

insurance and annuities to the general public and was the forerunner of modern stock

insurance companies. The Pennsylvania Company for Insurance on Lives and Granting

Annuities was the very first American company to offer annuities to the general public.

Annuities constituted a small share of the U.S. insurance market until the 1930s, when

two developments contributed to their growth. First, concerns about the stability of the

financial system drove investors to products offered by insurance companies, which were

perceived to be stable institutions that could make the payouts that annuities promised.

Flexible payment deferred annuities, which permit investors to save and accumulate

assets as well as draw down principal, grew rapidly in this period. Second, the group

annuity market for corporate pension plans began to develop in the 1930s.

The entire country was experiencing a new emphasis saving for a “rainy day.” The New

Deal Program introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) unveiled several

programs that encouraged individuals to save for their own retirement. Annuities

benefited from this new-found savings enthusiasm.

By today’s standard, the first modern-day annuities were quite simple. These contracts

guaranteed a return of principal, and offered a fixed rate of return from the insurance

15

company during the accumulation period (Fixed Annuity—see Chapter 3 for a full

discussion of Fixed Annuities). When it was time to withdraw from the annuity, you

could choose a fixed income for life, or payments over a set number of years. There were

few bells and whistles to choose from.

That all changed beginning in 1952, when the first variable annuity was created by the

College Retirement Equities Fund (CREF) to supplement a fixed-dollar annuity in

financing retirement pensions for teachers. Variable annuities credited interest based on

the performance of separate accounts inside the annuity. Variable annuity owners could

choose what type of accounts they wanted to use, and often received modest guarantees

from the issuer, in exchange for greater risks they (the owner) assumed. This type of

annuity was then made available to any individual, when the Variable Life Insurance

Company (VALIC) in 1960, began to market its own nonqualified variable annuity (See

Chapter 4 for a full discussion of Variable Annuities). It was the variable annuity that

boosted the popularity of annuities. Then in 1994, Keyport Life Insurance Company

introduced a new type of a fixed annuity called an index annuity (see Chapter 5 for a full

discussion of Index Annuities). And the rest is history.

U.S. Individual Annuity Sales

According to the Life Insurance Marketing Research Association (LIMRA), for full year

2014, total U.S. Individual Annuity sales were $235.8 billion, a 3 percent increase over

2013. Assets under management in annuities reached a record-high of nearly $2.7 trillion

(see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Total U. S. Individual Annuity Sales and Assets, 2000 – 2014 (billions)

Year

Sales

Assets

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

$190.0

187.6

218.3

218.0

221.0

217.0

238.0

257.0

265.0

235.0

222.0

238.0

219.0

230.0

235.8

$1,279

1,237

1,217

1,484

1,633

1,751

1,916

2,028

1,707

2,009

2,035

2,220

2,454

2,589

2,730ͤ

Source: LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute, U.S. Individual Annuities Survey

(based on data from 60 companies, representing 96 percent of total sales, March 2015).

16

Annuity Buyers

In a survey conducted by LIMRA, more than three-quarters of recent annuity buyers are

satisfied with their purchase of an annuity. LIMRA published this finding in a summary

of results from a survey of 1,200 consumers age 40 or over who purchased retail deferred

annuities within the past three years. The study was conducted in the third quarter of

2011.

Nearly 9 in 10 buyers of traditional fixed annuities are happy with their purchase, new

research reveals. The survey reveals that 86% of traditional fixed annuity buyers are

satisfied with their deferred annuity purchase. Likewise, most buyers are variable

annuities (75%) and indexed annuities (83%) are also satisfied with the purchases, the

survey reveals.

LIMRA observes that, of those who are satisfied, two-thirds of the VA households (61%

for indexed and half for traditional fixed) own two or more annuities. The study also

discloses that five of six deferred annuity buyers would recommend an annuity to their

friends or family.

Primary Uses of Annuities

The top reason consumers give for buying an annuity is to supplement their Social

Security or pension income. The second most popular reason is to accumulate assets for

retirement; this is especially true for individuals under age 60 (see Table 1.2).

Receiving guaranteed lifetime income is also a concern, especially for buyers aged 60

and older, the survey says. Annuity buyers’ single most important financial objective is to

have enough money to last their and/or their spouse’s lifetime.

Table 1.2

Intended Uses for Annuities

Source LIMRA Study, The “Deferred Annuity Buyer Attitudes and Behaviors” 2012

17

Annuity Outlook

Over the past few years, we saw some companies have slowed down or eliminated new

annuity sales, for various reasons. Many thought these departures would mark the

beginning of the end for the annuity market. Instead, it has created opportunities for

other companies to attract new customers and expand their holdings in one of the safest

investment options available today. We have seen an influx of private equity firms

entering the annuity market, specifically by purchasing interests in fixed-indexed

companies, as well as variable annuity blocks. Additionally, companies are innovating

with new products that are less capital-intensive, which may increase the capacity at

certain companies. The prognosis for 2015 and beyond shows increased investment in

annuities and new players in the marketplace.

18

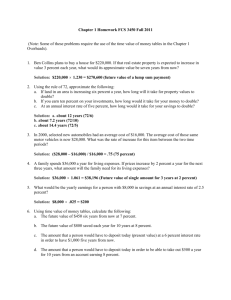

Chapter 1

Review Questions

1. What is the principal role of annuities?

(

(

(

(

) A. Indemnify individuals against market declines

) B. Indemnify individuals against the risk of dying too soon

) C. Indemnify individuals against the risk of outliving their resources

) D. Indemnify individuals against interest rate risk

2. What is the name of the extra factor that insurance companies can provide with the

means to guarantee annuity payments for life, regardless of how long that life lasts?

(

(

(

(

)

)

)

)

A.

B.

C.

D.

Survivorship factor

Gross interest factor

Annuity factor

Morbidity factor

3. In 1952, the first variable annuity was created by:

(

(

(

(

) A. The Romans

) B. College Retirement Equities Fund (CREF)

) C. Presbyterian ministers

) D. Variable Annuity Life Insurance Company (VALIC)

4. In 1960, the first non-qualified annuity was issued by:

(

(

(

(

) A. The Pennsylvania Company for Insurance on Lives and Granting Annuities

) B. The Teachers Insurance Association of America (TIAA)

) C. Variable Life Insurance Company (VALIC)

) D. College Retirement Equities Fund (CREF)

5. According to the Life Insurance Marketing Research Association (LIMRA), what is

the major reason why an individual purchases an annuity?

(

(

(

(

) A. Pay for LTC premiums

) B. Pay for emergencies only

) C. Leave an inheritance

) D. Supplement Social Security or pension income

19

This page left blank intentionally

20

CHAPTER 2

CLASSIFICATION OF ANNUITIES

Overview

Annuities can be categorized along many dimensions. In this chapter we will examine

the various ways annuities are classified. It also describes the age-old problems that

annuities attempt to solve and explains how annuities have been used over the years.

Finally, the chapter discusses how important annuities are to our society today.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Identify the various classifications of annuity contracts.

Demonstrate an understanding of the differences between a deferred annuity and

an immediate annuity;

Distinguish between an immediate annuity and a deferred income annuity;

Recognize the key elements of a variable annuity and fixed annuity; and

Identify the various payout options of an annuity in the distribution phase

Classification of Annuities

Annuities are flexible in that there are a number of classifications (options) available to

the purchaser (contract holder/owner) that will enable him or her to structure and design

the product to best suit his or her needs. Those options are:

Purchase Option

Date Benefit Payments Begin

Investment Options

Payout Options

Let’s review each of these classifications in greater detail beginning with the purchase

option.

21

Purchase Option

An annuity begins with a sum of money, called principal. Annuity principal is created

(or funded) in one of two ways; immediately with a single premium or over time with a

series of flexible premiums.

Single Premium

A single premium annuity is basically just what the name implies; an annuity that is

funded with a single, lump-sum premium, in which case the principal is created

immediately. Usually, this lump sum is fairly large.

Periodic (Flexible) Payment

But not everyone has a large lump sum with which to purchase an annuity. Annuities can

be funded through a series of periodic premiums that, over time, will amass an amount

large enough to buy a significant annuity benefit. At one time, it was common for

insurers to require that periodic annuity premiums be fixed and level, much like insurance

premiums. Today, it is more common to allow contract owner’s flexibility as to allowing

premiums of any size (within certain minimums and maximums, such as none less than

$25 or more than $1,000,000) and at virtually any frequency.

Date Benefit Payments Begin

The annuity is the only investment vehicle that has two phases based upon when the

income payment begins. The phases are:

Deferred (Accumulation Phase); or

Immediate. (Pay-out/Distribution Phase)

The main difference between deferred and immediate annuities is when annuity payments

begin. Every annuity has a scheduled maturity or annuitization date (usually age 90 or

age 95), which is the point the accumulated annuity funds are converted to the payout

mode and benefit payments to the annuitant are to begin.

According to LIMRA SRI, total sales of deferred annuities in 2014 were $218.0 billion

and immediate (income) annuities totaled $17.8 billion, (which includes $9.7 billion of

immediate annuities, $2.7 billion of deferred income annuities and $5.4 billion of

structured settlements).

22

Table 2.1

Annuity Industry Total U.S. Sales

Deferred vs. Immediate Annuities; 2000 - 2014 ($ billions)

YEAR

DEFERRED

IMMEDIATE

TOTAL

2000

$ 181.1

$ 8.8

$189.9

2001

175.0

10.3

185.3

2002

208.6

11.3

219.9

2003

207.5

8.3

215.8

2004

209.2

11.6

220.8

2005

204.9

11.5

216.4

2006

226.3

12.4

238.7

2007

243.8

13.0

256.8

2008

250.6

14.4

265.0

2009

225.4

13.2

238.6

2010

209.0

13.5

221.3

2011

227.1

13.2

240.3

2012

207.0

12.7

219.7

2013

216.0

14.1

230.1

2014

218.0

17.8

235.8

Source: LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute, U.S. Individual Annuities Survey

(based on data from 60 companies, representing 96 percent of total sales, March 2015).

Deferred Annuities

Deferred annuities are designed for long-term accumulation and can provide income

payments at some specified future date. A deferred annuity can be funded with either

periodic payments, commonly called flexible premium deferred annuities (FPDAs), or

funded with a single premium, in which case they’re called single premium deferred

annuities, or SPDAs. While a deferred annuity has the potential of providing a

guaranteed lifetime income at some point in the future, the current emphasis in a deferred

annuity is on accumulating funds rather than liquidating funds. An advantage that

deferred annuities have over many other long-term savings vehicles is that there are no

taxes (tax-deferral) paid on the accumulated earnings in an annuity until withdrawals are

made.

23

Immediate Annuities

An immediate annuity is designed primarily to pay income benefit payments one period

after purchase of the annuity. Since most immediate annuities make monthly payments,

an immediate annuity would typically pay its first payment one month (30 days) from the

purchase date. If, however, a client needs an annual income, the first payment will begin

one year from the purchase date. Thus, an immediate annuity has a relatively short

accumulation period. As you might guess immediate annuities can only be purchased

with a single premium payment and are often called single-premium immediate annuities,

or SPIA’s. The SPIA is the simplest individual annuity contract. In return for a single

premium payment, the annuitant receives a guaranteed stream of future payments that

begin immediately. These types of annuities cannot simultaneously accept periodic

funding payments by the owner and pay out income until the annuitant dies (a simple life

annuity), or when both the annuitant and a co-annuitant, such as a spouse, have died (a

joint life survivorship annuity). A simple life annuity is primarily designed to insure

annuitants against outliving their resources; a joint life survivorship annuity addresses

this risk and also provides retirement income for dependents. The average age of a SPIA

buyer is 73.

A once-snubbed annuity product—the immediate income annuity—appears to be gaining

a foothold in the broad annuity marketplace and in the practices of advisors who serve the

boomer and retirement income markets. According to LIMRA SRI, immediate income

annuity sales jumped 17 percent in 2014; totaling $9.7 billion (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2

Total Sales of Immediate Annuities 2000 – 2014 ($ billions)

YEAR

VARIABLE

FIXED

TOTAL

2000

$ 0.6

$ 8.0

$ 8.6

2001

0.6

9.6

10.2

2002

0.5

10.7

11.2

2003

0.5

4.8

5.3

2004

0.4

6.1

6.5

2005

0.6

6.3

6.9

2006

0.8

6.3

7.1

2007

0.3

6.7

7.0

2008

0.4

8.6

9.0

2009

0.1

7.5

7.6

2010

0.1

7.6

7.7

2011

0.1

8.1

8.1

2012

0.1

7.7

7.7

2013

0.1

8.3

8.4

24

2014

0.1

9.6

9.7

Source: Morningstar Inc. and LIMRA International, March 2015. Not including $5.3 of Structured Settlements.

Deferred Income Annuity

In recent years, a new form of retirement income annuity solution has been gaining

visibility: Deferred Income Annuity (DIA), also known as the longevity annuity.

According to LIMRA, deferred income annuities experienced record growth in 2014,

reaching $2.7 billion. This was 22 percent higher than sales in 2013. Like immediate

annuities, DIA’s suffered from falling interest rates in the fourth quarter. DIA sales were

$680 million in the fourth quarter 2014, 4 percent lower than fourth quarter 2013 results.

A "cousin" to the more familiar immediate annuity discussed above, the goal of the DIA

is similar - to provide income for life - but the payments do not begin until years (or even

decades) after the purchase. As such, these "deferred income annuities" can provide

significantly larger payments when they do begin - e.g., at age 85 - in light of both the

compounded interest and the mortality credits that would accrue over the intervening

time period.

Example: A couple both age 65, purchase a $100,000 DIA contract and stipulate that

payments will not begin until they reach age 85. However, the couple does reach age

85, payments of $2,656.20 will commence and be payable for as long as either

remains alive. Notably, the trade-off here is rather “extreme” – if the couple dies

anytime between now and age 85 (assuming both pass away), the $100,000 is lost.

However, if they merely live half way through age 88, they will have recovered their

entire principal, and from there will continue to receive $31,874.40/year thereafter, a

significant payoff for “just” $100,000 today.

Of course, the payout rates will vary depending on the starting age. If the 65-year-old

couple begins payments at age 75 instead of 85, the monthly payments are only

$934.18/month, instead of $2,656.20. The couple could also purchase a single premium

immediate annuity (SPIA) at age 65 with payments that start immediately, but the

payouts would only be $478.91/month. Thus, in essence, by introducing a 10-year

waiting period, the payments more than double; by waiting 20 years, the payments more

than quintuple! And if the couple starts even earlier, the payments are greater; a longevity

annuity purchased for $100,000 at age 55 with payments that don’t begin until age 85

receive a whopping $4,054.10/month ($48,649.20/year!) if at least one of them remains

alive to receive the payments! Alternatively, the couple could include a return-ofpremium death benefit (to the extent the original $100,000 is not recovered in annuity

payments, it is paid out at the second death to the beneficiary), which would drop the

payments to a still-significant $3,690.30/month. (Quotes are from Cannex, as of

7/8/2014)

In essence, the concept of the DIA is to truly hedge against longevity; while the couple

may receive limited payments if they don’t survive, the payments are very significant

25

relative to the starting principal if they do live long enough; in fact, the payments can be

so “leveraged” against mortality that the couple doesn’t actually need to set aside very

much in their 50s and 60s to fully “hedge” against living beyond age 85 (which also

makes it easier to invest for retirement when the time horizon is known and fixed to just

cover between now and age 85!).

In theory, a longevity annuity could be purchased with after-tax dollars (a non-qualified

annuity), or within a retirement account. After all, the reality is that for many people, the

bulk of their retirement savings is currently held within retirement accounts, and if there’s

a goal to use a longevity annuity to hedge against long life, those are the dollars to use!

Unfortunately, though, there’s a major problem with holding a longevity annuity inside of

a retirement account: how do you have a contract that doesn’t begin payments until age

85 held within an account that has required minimum distributions (RMDs) beginning at

age 70 ½!

We’ll that was settled when the IRS issued final regulations (T.D. 9673) that now permits

participants of IRAs and 401(a) qualified retirement plans, 403(b) plans and eligible

governmental 457 plans to purchase a “Qualified Longevity Annuity Contracts

(QLACs),” using a certain amount of their account balance, without having these

amounts count for calculating required minimum distributions (RMDs).

Investment Options

An annuity can be classified by two types of investment options. They are:

Fixed and

Variable

Fixed Annuity

A fixed annuity is an insurance contract in which the insurance company guarantees both

the earnings and principal (See Chapter 3 for a full discussion of fixed annuities).

Variable Annuity

A variable annuity, on the other hand, is an insurance contract where the contract holder

decides how to invest the money invested in sub-accounts (essentially mutual funds)

offered within the annuity. The value of the sub-accounts depends on the performance of

the funds chosen. The most popular type of annuity sold is the variable annuity (see

Chapter 4 for a full discussion of Variable Annuities).

26

Sales of Annuities

Table 2.3 illustrates the total U.S. Sales of Annuities between Variable Annuities and

Fixed Annuities. As you can see for the full year 2014, VA total sales fell 4 percent in

2014, totaling $140.1 billion. This represents the lowest annual VA sales since 2009. On

the other side, Fixed Annuity (FA) sales were $95.7 billion in 2014, improving 13

percent compared with 2013.

Table 2.3

Annuity Industry Total U.S. Sales

Variable vs. Fixed 2000 - 2014 ($ billions)

Year

Variable

Fixed

Total

2000

$ 137.3

$ 52.7

$190.0

2001

113.3

74.3

187.6

2002

115.0

103.3

218.3

2003

126.4

84.1

215.8

2004

133.0

88.0

221.0

2005

137.0

80.0

217.0

2006

160.0

78.0

238.0

2007

184.0

73.0

257.0

2008

156.0

109.0

265.0

2009

128.0

111.0

239.0

2010

140.0

82.0

222.0

2011

158.0

80.0

238.0

2012

147.0

72.0

219.0

2013

145.0

85.0

230.0

2014

140.1

95.7

235.8

Source: LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute, U.S. Individual Annuities Survey

(based on data from 60 companies, representing 96 percent of total sales, March 2015).

Payout Options

Another way to classify an annuity is the payout option chosen. Once an annuity matures

and its accumulated fund is converted to an income stream, a payout schedule is

established (see Table 2.4). There are a number of annuity payout options available:

Straight (Single) Life Income Option. A straight life income option (often called a

life annuity or single life annuity) pays the annuitant a guaranteed income for his

or her lifetime. This is the purest form of life annuitization. The straight life

27

income option pays out a higher amount of income than any other life with period

certain or a joint and survivor option, but they might not be higher than other

options (such as cash refund, installment refund, or pure period certain). At the

annuitant death, no further payments are made to anyone. If the annuitant dies

before the annuity fund (i.e., the principal) is depleted, the balance, in effect, is

“forfeited” to the insurer. It is used to provide payments to other annuitants who

live beyond the point where the income they receive equals their annuity

principal.

Cash Refund Option. A cash refund option provides a guaranteed income to the

annuitant for life and if the annuitant dies before the annuity fund (i.e., the

principal) is depleted, a lump-sum cash payment of the remainder is made to the

annuitant’s beneficiary. Thus, the beneficiary receives an amount equal to the

beginning annuity fund less the amount of income already paid to the deceased

annuitant.

Installment Refund Option. Like the cash refund, the installment refund option

guarantees that the total annuity fund will be paid to the annuitant or to his or her

beneficiary. The difference is that under the installment option, the fund

remaining at the annuitant’s death is paid to the beneficiary in the form of

continued annuity payments, not as a single lump sum.

Life with Period Certain Option. Also known as the life income with term certain

option, this payout approach is designed to pay the annuitant an income for life,

but guarantees a definite minimum period of payments. For an example, if an

individual has a ten-year period certain annuity, and receives monthly payments

for six years before dying, his or her beneficiary will receive the same payments

for four more years. Of course, if the annuitant died after receiving monthly

annuity payments for ten or more years, his or her beneficiary would receive

nothing from the annuity.

Joint and Full Survivor Option. The joint and full survivor option provides for

payment of the annuity to two people. If either person dies, the same income

payments continue to the survivor for life. When the surviving annuitant dies, no

further payments are made to anyone. There are other joint arrangements offered

by many companies:

o Joint and Two-Thirds Survivor. This is the same as the above

arrangement, except that the survivor’s income is reduced to two-thirds of

the original joint income.

o Joint and One-Half Survivor. This is the same as the above arrangement

except that the survivor’s income is reduced to one-half of the original

joint income.

Period Certain. The period certain option is not based on life contingency;

instead it guarantees benefit payments for a certain period of time, such as 5, 10,

15, or 20 years, whether or not the annuitant is living. At the end of the specified

term, payments cease.

Table 2.4 illustrates the comparison of the monthly settlement cash flow options for a

Male and Female age 65 with $100,000 purchase payment and income begins one month

after purchase date (as of February 9, 2015). As you can see the single life income with

28

no payments to beneficiaries pays out the highest amount of income at $550 for a male

and $512 for a female per month. Notice as well, the 5-year period certain payment of

$1,703, a payment of both principal and interest of 20.44%.

Table 2.4

Comparison of Monthly Settlement Options

Cash

Flow

Female

Estimated

Monthly

Income

Cash

Flow

$542

6.50%

$517

6.20%

Single life w/10 years certain

$526

6.31%

$506

6.07%

Single life w/20 years certain

$482

5.78%

$469

5.63%

Single Life w/Installment (Cash) Refund

$492

5.90%

$472

Income Payment Options

Single life

beneficiaries

income

no

payments

Male

Estimated

Monthly

Income

to

5.66%

Income Payment Options

Estimated Monthly

Income

Cash Flow

Joint Life 100% Survivor (no payments to

beneficiaries)

$441

5.29%

Joint Life 100% Survivor (10 year certain)

$439

5.27%

5-Year Period Certain

$1,703

20.44%

10-Year Period Certain

$910

10.92%

Source: http://www.immediateannuities.com/; Date 3-22-2015. Cash flow –monthly income times twelve divided by

the deposit amount. Cash flow percentage is significantly higher than the internal rate credited to the premium.

Contract options dramatically change the pay-out on an IA, as shown by the projected monthly payout on a $100,000

annuity purchased by a hypothetical 65-y.o. M/F.

29

Chapter 2

Review Questions

1. What is the most popular type of annuity sold?

(

(

(

(

2.

)

)

)

)

A.

B.

C.

D.

Fixed Annuity

Deferred Annuity

Immediate Annuity

Variable Annuity

Which of the following types of annuities is basically a single premium deferred

annuity with an income annuity component?

(

(

(

(

)

)

)

)

A.

B.

C.

D.

Fixed Annuity

Deferred Annuity

Immediate Annuity

Deferred Income Annuity

3. What is the average age of a SPIA buyer?

(

(

(

(

)

)

)

)

A.

B.

C.

D.

55

73

60

63

4. Which type of annuity will begin to make annuity payments one month after

the purchase payment?

(

(

(

(

) A. Index Annuity

) B. Period Certain Annuity

) C. Single Premium Immediate Annuity

) D. Deferred Income Annuity

5. Which annuity payout option is the purest form of life annuitization?

(

(

(

(

)

)

)

)

A.

B.

C.

D.

Straight (single) life income

Joint and survivor

Life with 10 years certain

Life with 20 years certain

30

CHAPTER 3

FIXED ANNUITIES

Overview

Fixed annuities place the investment risk on the insurer. One of the major features of a

“fixed” annuity is safety of principal and also safety in that the rate of return is certain.

Over the past several years, we have seen the sales of fixed annuities decline drastically

due to the overall low interest rate in the financial markets. However, as interest rates

begin to tick up, we certainly are seeing an insurgence of interest in fixed annuities with

both deferred and income payout annuities.

In this chapter, we will examine the basic advantages and disadvantages of fixed

annuities, the sales of fixed annuities as well as the various types of fixed annuities. We

will also examine how fixed annuities are credited with interest payments.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Identify the advantages and disadvantages of fixed annuities;

Identify the various expenses of a fixed annuity;

Explain the various types of fixed annuities;

Explain the various interest crediting methods of fixed annuities;

Demonstrate differences between portfolio rate and new money rate; and

Demonstrate the payout options of a fixed annuity.

Advantages of Fixed Annuities

One of the major features of a “fixed” annuity is safety. Safety of principal and also

safety in that the rate of return is certain. The fixed aspect of the annuity also offers

safety in that the annuity holder does not take on responsibility for making any decisions

about where or in what amount the funds in his or her annuity should be invested. This is

in contrast to a variable annuity in which the annuity holder does take on this type of

responsibility.

31

Premiums made to a fixed annuity are invested in the insurance companies’ general

account. The company then invests the premiums it receives in a manner that will allow

it to credit the rates it has stated it will pay. The interest rate chosen by the insurance

company during the first year is meant to be competitive with rates currently offered on

other financial vehicles.

Disadvantages of Fixed Annuities

Like everything else in life, even though fixed annuities offer several advantages, they

also have their disadvantages. Probably the most significant disadvantage is that by

locking in the fixed annuity’s fixed rate of interest, the policyholder might lose out on

any potentially greater gains that could be realized if the same funds were invested in the

stock market.

A second potential disadvantage of the fixed annuity involves the fact that the benefit

payout amount will be a fixed amount. While this fixed payout amount will be viewed

by some annuity holders as a decided advantage, others will realize that, over time, the

fixed benefit amount will lose ground against inflation with the potential reduction of

spending power over time. For example, at an inflation rate of 3 percent per year, the real

value of annuity payouts in the first year of an annuity liquidation period is more than

twice that of the name nominal payout 24 years later. At an inflation rate of 4 percent,

the purchasing power of the fixed monthly payment would be halved in only 18 years.

Fixed Annuity Fees and Expenses

Fixed annuity fees and expenses generally cover the insurance company's administrative

expenses, the cost of offering the annuitization guarantee and profits to the insurance

company and sales agent.

Contract Charge

The rate quoted is the rate paid. Some fixed annuities may assess an annual contract fee,

typically around $30 to $40.

Interest Spread

Just like other investments fixed annuities have fees and expenses. Most fees and

expenses of a fixed annuity are factored into the stated annual percentage rate (APR) the

investor is quoted, this is known as the interest spread.

Surrender Charges

Most fixed annuity contracts impose a contract surrender charge on partial and full

surrenders from the contract for a period of time after the annuity is purchased. This

32

surrender charge is intended to discourage annuity holders from surrendering the contract

and to allow the insurance company to recover its costs if the contract does not remain in

force over a specific period of time.

Fixed Annuity Sales

According to LIMRA SRI, total U.S Fixed Annuity sales increased 13 percent in 2014,

totaling $95.7 billion (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

Fixed Annuity Sales and Assets, 2000 - 2014 ($ billions)

YEAR

TOTAL SALES

NET ASSETS

2000

$ 52.7

$ 322

2001

74.3

351

2002

103.3

421

2003

84.1

490

2004

86.7

497

2005

77.0

520

2006

74.0

519

2007

66.6

511

2008

106.7

556

2009

104.3

620

2010

82.0

659

2011

81.0

675

2012

72.0

692

2013

85.0

715

2014

95.7

745ͤ

Source: LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute, U.S. Individual Annuities Survey

(based on data from 60 companies, representing 96 percent of total sales, March 2015).

Types of Fixed Annuities

The basic types of deferred fixed annuities can be broken down into the following

categories. They are:

Book value deferred annuity products earn a fixed rate for a guaranteed period.

The surrender value is based on the annuity’s purchase value plus a credited

33

interest, net of any charges. Book value products are the predominant fixed

annuity type sold in banks.

Market value adjusted annuities are similar to book value deferred annuities but

the surrender value is subject to a market value adjustment based on interest rate