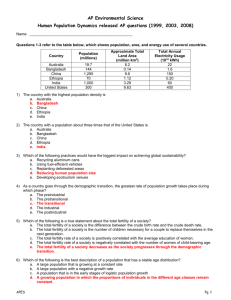

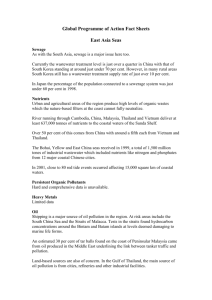

The Population of Southeast Asia - Nus ari

advertisement