Task Interdependence between Economic and Non

advertisement

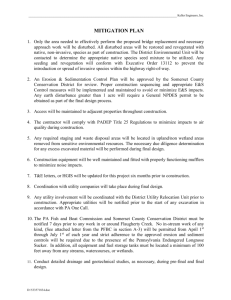

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IN ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT Task Interdependence between Economic and Non-economic Goals and the Family Owner’s Decision to Hire a Family or Nonfamily Manager: A Multitask Model Joern Block, Jenny Kragl, Guoqian Xi Discussion Paper No. 15-15 GERMAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION – GEABA Task Interdependence Between Economic and Non-economic Goals and the Family Owner’s Decision to Hire a Family or Nonfamily Manager: A Multitask Model Joern Block, Jenny Kragly, and Guoqian Xiz Preliminary and incomplete - do not cite or circulate. April 13, 2015 Corresponding author; Universität Trier, Faculty IV, Department of Business Administration, e-mail: block@uni-trier.de. y EBS Universität für Wirtschaft und Recht, Department of Management & Economics, e-mail: jenny.kragl@ebs.edu. z Universität Trier, Faculty IV, Department of Business Administration, e-mail: xgq.natalie@gmail.com. 1 1 Introduction Family …rms and family owners pursue both economic and non-economic goals, where the noneconomic goals are mostly related to family goals such as family harmony or family reputation (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008; Chrisman, Chua, Pearson, & Barnett, 2012). Managers in family …rms need to ful…ll both types of goals. The recruitment of top management team members in family …rms and the decision to hire a family or a nonfamily manager is therefore often a complex process and depends on various factors such as the availability of family managers, the importance of family goals, and the family’s risk attitude towards non-economic (family) goals (Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007). So far, however, prior research has not considered how the interdependence between the two types of goals in‡uences top management recruitment decisions in family …rms. Our paper makes a …rst step in this direction. We analyze how task interdependence between economic and non-economic goals in family …rms in‡uences the decision to hire a family or a nonfamily manager. The tasks of ful…lling economic and non-economic goals in family …rms can be either substitutes or complements. That is, they can either reinforce or exclude each other. As an example for the two tasks being substitutes consider the situation where the manager, for economic reasons, is forced shutting down a factory in the family’s and the family …rm’s home region. Shutting down the factory and laying o¤ its employees may help the …rm to survive and ful…ll the family’s economic goals but does harm to the family’s reputation in the public. Another example is when the manager spends a lot of time training and nurturing a potential family successor while being busy on expanding the business into a new market. As an example for the two tasks being complements consider the case where the manager helps to solve a family con‡ict which was visible in the public contributing to a negative public …rm image and creating mistrust in the …rm and between its stakeholders. By solving the family con‡ict, the family harmony is restored, decision-making becomes quicker, and the …rm looks more attractive as an employer for potential employees. The manager has limited time and e¤ort that he can put into doing the respective tasks. The interdependence between both tasks has an in‡uence on the manager’s distribution of his e¤orts towards the two tasks. Our study aims to understand how the family owner’s decision to hire a family or a nonfamily manager depends on whether the two tasks are substitutes or complements. We use a multitask principal-agent model to answer this research question. In the model, the family …rm owner (principal) chooses a family or a nonfamily manager (agent). The family owner values both economic and non-economic goals and the manager has the task to ful…ll both types of goals. Yet the manager’s work e¤ort is his private information so that a moralhazard problem arises. While the manager’s performance regarding non-economic goals cannot be objectively assessed, there is a measure of economic performance which the …rm owner uses in an incentive contract. We model two important characteristics in which the two types of managers di¤er. First, we assume that the nonfamily manager has a higher ability than the family manager with regard to economic goals as he is drawn from a pool of suitable candidates 2 (Burkart, Panunzi, & Shleifer, 2003; Pérez-González, 2006). Second, we assume that, in contrast to the nonfamily manager, the family manager has a personal interest in the pursuit of noneconomic goals (Chrisman, Chua, Pearson, & Barnett, 2012). We argue that the valuation of non-economic goals is decreasing over the family generation, and the family manager’s valuation falls, however, below that of the …rm owner. We then analyze how the task interdependence between ful…lling economic and non-economic goals in‡uences how the manager distributes his e¤ort between the two tasks and how this a¤ects the family’s utility as an owner. Our main …ndings are threefold. First, we …nd that the nonfamily manager does not put any e¤ort into pursuing the family’s non-economic goals if the two tasks are substitutes. The reason is that any e¤ort the manager would put into non-economic goals not only decreases his incentive pay for economic performance but moreover impedes his work e¤ort in the latter task. Hiring the family manager is optimal if the family manager’s valuation of the non-economic goals is close to that of the …rm owner and/or the family manager’s ability in the economic task does not di¤er too much from that of the nonfamily manager. Secondly, if the two tasks are complements, the owner is more likely to choose the family manager, the more aligned the latter’s valuation of the non-economic goals with the former’s. Intuitively, with complementary tasks, both types of managers will allocate some e¤ort to both tasks although the non-economic goal is not explicitly rewarded. This occurs because enhancing non-economic goals at the same time facilitates raising economic performance and hence increases the expected incentive pay. However, the family manager moreover has an intrinsic incentive to pursue the non-economic goals. The stronger this incentive, the more valuable is the family manager to the …rm. Thirdly, if the two tasks are complements, the owner is more likely to choose the nonfamily manager as the complementarity of the two tasks increases. This is because strong task complementarities also induce the nonfamily manager to comprehensively engage for the non-economic goals. When hiring the nonfamily manager, the …rm owner additionally bene…ts from that manager’s higher ability in the economic task. The remainder of the study is structured as follows. The following section presents the model. We introduce the basic assumptions and then we solve the model for the optimal incentive contract. The fourth section presents our main …ndings regarding the optimal hiring decision. Section …ve o¤ers a discussion of our main results, and the …nal section concludes, thereby highlighting the avenues for further research. 2 2.1 The Model Assumptions We model a principal-agent relationship in which the family-…rm owner (principal) selects one out of two candidates (agents i = F; N ) to manage the …rm. The former has two options; hiring a family manager (i = F ), that is, a person with family ties to the …rm, or a nonfamily manager (i = N ), that is, somebody from outside the familiar context of the …rm. All parties are risk neutral. Managing the …rm requires ful…lling two tasks; enhancing the …rm’s economic 3 performance and the family’s non-economic goals such as preserving and fostering the family’s reputation. The tasks cannot be split between managers; that is, just one manager will be hired.1 By e¤ort ei1 we denote all activities manager i undertakes to raise the …rm’s economic performance xi , e.g., the stock price. E¤ort ei2 in the second task summarizes the manager’s e¤orts related to achieving the family’s non-economic goals yi . The manager’s exerted e¤ort levels are not veri…able by the …rm owner, implying a moral-hazard problem. Performance in the …rst task can, however, be assessed using the veri…able measure of economic performance xi : xi = ei1 + 1; 1 N (0; 2 1 ); i = F; N; (1) where 1 denotes the random shock to economic performance outside the manager’s control. By contrast, the non-economic outcome yi is not veri…able:2 yi = ei2 + 2; 2 N (0; 2 2 ); i = F; N; (2) where similarly 2 denotes the exogenous random term. For simplicity, we assume the random terms ( 1 , 2 ) to be independent. The …rm owner o¤ers the manager an incentive contract which speci…es a …xed wage i and an incentive rate i 0 per unit of economic performance xi .3 Accordingly, manager i’s wage is given by wi = i + i xi ; i = F; N: (3) The manager is …nancially constrained, hence no negative payment is allowed. When hiring manager i, the …rm owner’s utility is given by the sum of economic and non-economic outcome minus wage payments: wi ; i = F; N: (4) i = xi + yi According to the above speci…cation, for simplicity, we assume the …rm owner to value economic performance goal as important as the non-economic outcome.4 Manager i’s utility is Ui = i + i xi + i yi c (ei1 ; ei2 ) ; i = F; N; where c (ei1 ; ei2 ) denotes his cost of exerting e¤ort. In the utility function, (5) i denotes manager i’s 1 If the two tasks could be separated, the …rm owner could hire both managers, assigning one task to each of them, which is, however, not plausible in many management cases. Our interest lies in the understanding of the …rm owner’s choice when she faces the situation where she is forced to choose one out of two managers to conduct both tasks. 2 Note that non-economic goals are often hardly objectively measurable. On the one hand, non-economic goals frequently refer to "soft" criteria such as reputation. On the other hand, e¤orts related to these goals often take e¤ect only in the future. 3 That is, in line with most real-life cases, we exclude the theoretical possibility of punishing good performance. 4 This assumption greatly simpli…es the exposition of the model. A more general formulation allows for di¤erent valuations of economic and non-economic goals: i = axi + byi wi ; i = F; N , where a and b denote the respective weights the …rm owner assigns to the two goals. While such a model provides further results, assuming a = b = 1 does not change any of the main results of our paper. 4 personal valuation of the non-economic outcome. We assume that the nonfamily manager does not bene…t from pursuing non-economic goals, thus N = 0. By contrast, the family manager’s valuation of the non-economic outcome is positive. Moreover, we assume that his valuation falls below that of the …rm owner, hence F =: 2 (0; 1).5 Manager i’s e¤ort cost function is given by c (ei1 ; ei2 ) = 1 2 2Di ei1 + 12 e2i2 + cei1 ei2 ; i = F; N; (6) where Di 1 denotes manager i’s ability in the task related to economic performance. Specifically, we assume the nonfamily manager to have a higher ability in that task than the family manager.6 Accordingly, we assume DF = 1 and DN =: D > 1. In the cost function, p1 ; p1 c2 is a measure of task interdependence.7 If c > 0, the two tasks are substitutes, Di Di i.e., the tasks compete for the manager’s attention so that he …nds it harder to engage in one task when he is already working on the other. By contrast, if c < 0, tasks are complements. In that case, doing one task reduces the manager’s marginal e¤ort costs for the other task. Obviously, tasks are independent if c = 0.8 The timing is as follows. First, the …rm owner decides whether to hire the family or the nonfamily manager. Then she o¤ers that manager an employment (incentive) contract. Third, the manager decides whether to accept that contract or reject it. In the latter case, the manager obtains his outside option, which we, for simplicity, set to zero. If the manager accepts the contract, he chooses the e¤ort levels ei1 and ei2 . Fourth, economic performance xi and the non-economic outcome yi are realized. Finally, the manager is paid according to the contract. 2.2 First-best Solution As a benchmark, we …rst determine the e¢ cient e¤ort levels if e¤ort is contractible for both types of managers. The …rm owner’s optimization problem under the …rst-best solution is maximizing expected utility so that the manager participates in the contract. In the Appendix, we present the solution to this problem. The …rm owner’s …rst-best expected utility is given by: E( ~i ) = Di (1 2c (1 + i )) + (1 + 2(1 c2 Di ) i) 2 ; i = F; N: (7) 5 Recall that, by the …rm owner’s utility function, her valuation of non-economic goals is one. We argue that a family member’s valuation of non-economic goals is decreasing over the family generation. 6 This assumption is justi…ed by previous empirical evidence (see, e.g., the study by Pérez-González, 2006), and it is in alignment with the theoretical paper by Burkart, Panunzi, & Shleifer (2003). The respective argument is that nonfamily managers are chosen from a large sample pool of candidates who are thus likely to be superior than family managers with regard to managerial abilities. 1 c 7 The cost function can be written as c (ei1 ; ei2 ) = 21 eT Ce, where e = (ei1 ; ei2 )T and C = Di is the c 1 Hessian matrix. The restriction c 2 p1 ; p1 Di Di ensures that the cost function is strictly convex, and the matrix C is positive de…nite. In the model, we also assume that c > 0 is not too large to exclude the unrealistic cases of negative e¤ort levels. 8 In our analysis, we will focus on the more interesting cases in which c 6= 0. 5 By inspection of the …rst-best utility function, …rm pro…t is strictly increasing in when tasks are complements (c < 0). 3 i and Di Optimal Incentive Contract In this section, we analyze the case with non-veri…able e¤ort, hence the moral-hazard problem. The …rm owner’s maximization problem is given by: max ei1 ;ei2 ; s.t. i 0 ei1 + ei2 ( i + i ei1 ) 1 2 + i ei1 + i ei2 ( 2D e + 12 e2i2 + cei1 ei2 ) 0; i i1 1 ei1 ; ei2 = arg max i + i e^i1 + i e^i2 ( 2D e^i1 + 12 e^i2 + c^ ei1 e^i2 ); i 0 for all xi i + i xi i (8) The …rst constraint is the participation constraint, the second constraint is the incentivecompatibility constraint, ensuring that the manager maximizes his own expected utility for any given incentive rate i . The last constraint is the non-negativity constraint, guaranteeing that negative payments cannot arise. The formal solution to the problem is again relegated to the Appendix. We assume that ei1 ; ei2 ; i 0, i.e., c is not too large. Recall, that, for the family manager, it holds that F = and DF = 1 while, for the nonfamily manager, it holds that N = 0 and DN = D. Accordingly, the above results yield the …xed wage, incentive rate and e¤ort levels for the two types of manager under the optimal incentive contract, respectively. For the family manager, we obtain: F = 0; F = eF 1 eF 2 (9) 1 + c( 1) ; 2 1 c(1 + ) = ; 2(1 c2 ) 2 + ((1 )c = 2(1 c2 ) 6 (10) (11) 1)c : (12) For the nonfamily manager, i = N , we have:9 N N eN 1 eN 2 = 0; 8 < 1 c if c 0 = ; 2 : 1 if c > 0 2 8 < D(1 c) if c 0 2(1 c2 D) ; = : D if c > 0 2 8 cD(1 c) < if c 0 2 2(1 c D) = : : 0 if c > 0 (13) (14) (15) (16) The following lemma highlights a …rst interesting insight regarding the nonfamily manager’s e¤ort choice under the optimal incentive contract as formally stated in the above results. Lemma 1 If the two tasks are substitutes, c > 0, the nonfamily manager does not put any e¤ ort into pursuing the family’s non-economic goals; eN 2 (D; c > 0) = 0. The manager’s e¤ort in pursuing the family’s non-economic goals is not monetarily incentivized by the …rm owner. In contrast to the family manager whose name is tied to the family …rm, the nonfamily manager has no intrinsic motivation to achieve the non-economic goals. If the two tasks are substitutes, doing a task such as nurturing a potential family successor makes working in the other task related to produce economic performance more di¢ cult and costly. Hence, the nonfamily manager would rather focus on the economic goals only. Using the results above, we calculate the …rm owner’s utility under the optimal incentive contract. For the family manager ( F = , DF = 1) and the nonfamily manager ( N = 0, DN = D), the …rm owner’s respective levels of expected utility are given by: c2 ( 1)2 2c( + 1) + 1 + 4 ; 4(1 c2 ) 8 2 < D(1 c) if c 0 4(1 c2 D) E( N ) = : : D if c > 0 4 E( F) = (17) (18) In the following section, we take a closer look at the …rm owner’s utility, depending on the managers’characteristics ( ; D) and the task interdependence as characterized by c. Then we derive the optimal hiring decision, depending on the foregoing parameters. 4 Whom to Hire: Family versus Nonfamily Manager In order to determine which manager the …rm owner should optimally hire, we analyze the di¤erence in utility between hiring a family and a nonfamily manager. That di¤erence is given 9 We derive N ; eN 1 ; eN 2 explicitly in the Appendix. 7 by: E( F) E( N) = 8 (1 > > < > > : c)2 (1 c2 ( D) + (1 Dc2 )( 2 c2 2 c2 2c + 4 ) 4(1 c2 )(1 c2 D) 1)2 2c(1 + ) + 1 + 4 D(1 c2 ) 4(1 c2 ) if c 0 : (19) if c > 0 We initially consider the case where economic and noneconomic goals are substitutes (c > 0). Proposition 1 If the two tasks are substitutes, c > 0, the …rm owner’s utility when hiring a family manager exceeds the utility when hiring a nonfamily manager if > 1 ;where 1 = p 1 (c c+ 2 c 1) (c + 1) ( 4c + c2 D + 4) + c2 2 : Proof. See the Appendix. The result shows that should be su¢ ciently large to ensure the di¤erence of utility to be positive.10 Moreover, it is easily checked that the di¤erence of utility E( F ) E( N ) is decreasing in D: Accordingly, we can draw a conclusion for the optimal hiring decision. Corollary 1 If the tasks are substitutes, c > 0, the family …rm owner might be better o¤ by choosing the family manager although the nonfamily manager has a higher ability in the task related to economic goals. That case is more likely to arise if the family manager’s valuation of non-economic goals is close to that of the …rm owner and/or the family manager’s ability is not too di¤ erent from that of the nonfamily manager. The family manager is more likely to be chosen by the …rm owner if his valuation of the non-economic goals is su¢ ciently large. In our case, this signi…es that the family manager’s goal is aligned with the …rm owner’s. Family managers who view family reputation or …rm image as a re‡ection of their own public image exert e¤orts in protecting the family’s non-economic goals from being harmed. When the manager’s valuation is su¢ ciently strong, the e¤ort he exerts will be higher, then the …rm owner’s total utility achieving from both economic and non-economic goals will increase. Now consider the case where the tasks are complements (c < 0). Inspection of the …rm owner’s utility di¤erence given in (19) yields the following result. Proposition 2 If the two tasks are complements, c < 0, the …rm owner’s utility when hiring a family manager exceeds the utility when hiring a nonfamily manager if > 2 ;where 2 = (c 1) 4 c D c2 Proof. See Appendix c+ p (c2 D 1) (c + 1) (3c2 D + c3 D 10 4) + 2c2 D + c3 D 2 : Recall that, cannot not exceed 1; as we assume that the family manager’s valuation of the non-economic goals is smaller than that of the …rm owner, . 8 Similar to the substitute case, the di¤erence of utility is positive if is su¢ ciently large. Again, E( F ) E( N ) is decreasing in D: Accordingly, we can draw a conclusion for the optimal hiring decision in the case of task complementarities. Corollary 2 If the two tasks are complements, c < 0, the family …rm owner is more likely to choose the family manager the more aligned the latter’s valuation of the non-economic goals with the former’s. The family manager has an intrinsic motivation to ful…ll the family’s non-economic goals even though he does not receive any monetary compensation for this task. The more the family manager cares about family reputation or family harmony, the more e¤ort he will put into doing both tasks, hence increasing the …rm owner’s total utility. We now analyze how the complementarity of the tasks a¤ects the …rm owner’s decision, that is, how the …rm owner’s utility varies in c: Proposition 3 If the two tasks are complements, c < 0, the …rm owner’s di¤ erence of utility E( F ) E( N ) is decreasing in the complementarity of the two tasks. Proof. See the Appendix. Based on this …nding, we conclude the following for the …rm owner’s hiring decision. Corollary 3 If the two tasks are complements, c < 0, the family …rm owner is more likely to choose the nonfamily manager as the complementarity of the two tasks increases. Our model shows that, although the family manager personally cares for the non-economic goals, the …rm owner might favor the nonfamily manager over the family manager if tasks are complements. This is the case when the complementarity of the tasks is su¢ ciently strong and/or the nonfamily manager is much better than the family manager at task related to economic goals. Even though the nonfamily manager does not receive any compensation from the …rm owner, he will put e¤ort into pursuing the family’s non-economic goals when the two tasks are complements. The more complementary the two tasks are, the more likely it is that doing one task reduces the marginal cost of another task, thus the nonfamily manager will put more e¤ort into both tasks. Hence, the …rm owner’s utility increases. 5 Discussion Our economic model shows that it can be an optimal and rational choice for family owners to hire a family manager with a low ability regarding the ful…llment of economic goals. This situation occurs when the tasks of ful…lling economic and non-economic goals are substitutes and the non-economic goals are di¢ cult to measure. In such a situation a highly quali…ed nonfamily manager would rationally choose to put all his e¤orts in the ful…llment of economic goals and neglect the non-economic goals such as family harmony or family reputation, which the family cares about. 9 With this result, our paper contributes to prior research about the top management hiring decisions in family …rms (Chrisman, Memili, & Misra, 2013; Vandekerkhof, Steijvers, Hendriks, & Voordeckers, in press; Salvato, Minichilli, & Piccarreta, 2012). In contrast to prior research, our model shows that it can be a rational and utility-maximizing choice of family owners to recruit a member of their own family into a top management position even though he is less quali…ed in terms of economic goals than a nonfamily manager drawn from a larger pool of potential candidates (Burkart, Panunzi, & Shleifer, 2003). It should be noted that the preference for the family candidate is not due to other reasons such as nepotism (Jaskiewicz, Uhlenbruck, Balkin, & Reay, 2013), exploitation of minority shareholders (Morck &Yeung, 2003), the family …rm’s inability to attract good nonfamily candidates (Chrisman, Memili, & Misra, 2013) or irrational decision making of family owners (Kets de Vries, 1993). Thus, our model o¤ers a new explanation why family …rms stick to family members as top managers even though they are not as well quali…ed (in terms of economic goals) than outside nonfamily candidates are. The situation di¤ers, however, when the tasks of ful…lling economic and non-economic goals are complements and the ful…llment of one task helps to ful…l the other task. In such a situation, the hiring decision should be based primarily on the ability of managers to ful…ll economic goals. The ful…llment of economic goals helps also to ful…ll non-economic (family) goals. In such a situation, the likelihood that the family manager is the best candidate from the family owner’s perspective decreases strongly as the family manager is drawn from a much smaller pool of quali…ed candidates and usually has less outside …rm and industry experience than comparable nonfamily managers. This result helps to understand why in some industries and some family contexts the family manager is the preferred and optimal choice whereas in other industry and family contexts the nonfamily manager is preferred. The more the tasks of ful…lling economic and non-economic goals are complements and not substitutes, the better the chances of the nonfamily manager to get hired by a family …rm. Next to the literature about the top management hiring decisions in family …rms, our paper also contributes to the discussion how family owner’s economic and non-economic goals interrelate with each other and how this in‡uences family …rm decision making. This point was raised by Berrone et al., (2012) in their summary of open questions related to the concept of socio-emotional wealth. 6 Further Research The model o¤ers several interesting avenues for further research. Our model is about the selection of a single family or nonfamily manager. The model could be extended to the case of management teams, where both family and nonfamily managers prevail (Patel & Cooper, 2014). In this case, the family owner being principal hires two or more managers. Another avenue would be to extend the model to the case where several principals with di¤erent objectives exist. This case refers to family …rms with minority nonfamily owners. 10 Appendix First-best Solution With contractible e¤ort and in the absence of …nancial constraints, the …rm owner o¤ers manager i a …xed wage w ~i to be paid i¤ the manager exerts at least the pro…t-maximizing e¤ort levels e~i1 ; e~i2 . The …rm owner’s maximization problem is given by11 : max ei1 ;ei2 0;wi s.t. ei1 + ei2 wi + i ei2 wi 1 2 e + 12 e2i2 + cei1 ei2 ) ( 2D i i1 (20) 0 The constraint to the problem is the participation constraint since it ensures that the manager accepts the contract. As the …xed wage negatively enters the …rm owner’s objective function, she will reduce it as much as possible so that the constraint becomes binding at the optimum. Hence, we obtain: 1 2 e + 21 e2i2 + cei1 ei2 (21) w ~i = 2D i ei2 : i i1 Substituting w ~i into the …rm owner’s utility maximization problem and calculating the …rst-order conditions yields: Di (1 c(1 + i )) ; i = F; N; 1 c2 Di 1 + i cDi e~i2 = ; i = F; N: 1 c2 Di e~i1 = (22) (23) We assume e~i1 ; e~i2 0, hence c not too large. The …rm owner’s …rst-best utility becomes: E( ~i ) = Di (1 2c(1 + i )) + ( 2(1 c2 Di ) i + 1)2 ; i = F; N: (24) Recall, that, for the family manager, i = F , it holds that i = and Di = 1. Hence, for the …rst-best e¤ort and …rm pro…t when hiring the family manager, we obtain: c(1 + ) ; 1 c2 1+ c e~F 2 = ; 2 1 c 1 + (1 + )(1 + E( ~F ) = 2(1 c2 ) e~F 1 = 1 For the nonfamily manager, i = N , it holds that 11 i (25) (26) 2c) : (27) = 0 and Di = D. Hence, for the …rst-best We assume that i is small enough so that w ~i is non-negative. In other words: We focus on the most plausible case where the family manager does not enjoy working for non-economic goals so much that he would accept even a negative wage. 11 e¢ cient e¤ort and …rm pro…t when hiring the nonfamily manager, we obtain: D(1 c) ; 1 c2 D 1 cD e~N 2 = ; 1 c2 D D(1 2c) + 1 E( ~N ) = : 2(1 c2 D) (28) e~N 1 = (29) (30) Comparing the …rm owner’s expected utilities for i = F; N , respectively, veri…es that hiring the family manager yields higher pro…t if: (1 + (1 + )(1 + c2 D) > (1 + D (1 2c)) 2(1 2c)) 2(1 c2 ) (31) Solution to the Optimal Incentive Contract (Second-best Solution) Manager i maximizes his expected utility: max i ei1 ;ei2 0 + i ei1 + i ei2 1 2 e + 12 e2i2 + cei1 ei2 ) ( 2D i i1 (32) The …rst-order conditions are given by: Di ( i c i ) ; i = F; N; 1 c2 Di c i Di i i = F; N: ei2 = 1 c2 Di ei1 = (33) (34) Hence, the …rm owner’s problem becomes: max ei1 ;ei2 ; s.t. i 0 ei1 + ei2 ( i + i ei1 ) 1 2 + i ei1 + i ei2 ( 2D e + 12 e2i2 + cei1 ei2 ) i i1 (33); (34) 0 for all xi : i + i xi i 0; (35) Since we have i 0, the ex-post wage payment as given in the last constraint is continuously increasing in xi . Accordingly, if the constraint holds for the lowest possible realization of xi , it holds for all xi . This implies that we must have i 0. As the …xed wage i negatively enters the …rm owner’s objective function, she will choose it as small as possible so that the constraint becomes binding in the optimum, hence i = 0. After substituting i , ei1 , ei2 into the …rm owner’s maximization problem, the …rst-order condition with respect to i is given by: i = 1+( i 1) c 2 12 ; i = F; N: (36) Substituting i into equations (33),(34) yields the optimal e¤ort levels: Di (1 (1 + i )c) ; i = F; N; 2(1 c2 Di ) 2 i + ((1 1)cDi i) c ei2 = ; i = F; N: 2 2(1 c Di ) ei1 = As before, we assume ei1 ; ei2 0, hence c is not too large. Substituting owner’s utility under the optimal incentive contract becomes: E( i ) = cDi (c( i 1)2 2( i + 1)) + Di + 4 i ; 4(1 c2 Di ) (37) (38) i , ei1 , ei2 , the …rm i = F; N: (39) Using that F = ; DF = 1; we obtain the optimal …xed wage, incentive rate and e¤ort levels for the family manager as given in equations (9), (10), (11) and (12). For the nonfamily manager ( N = 0; DN = D), we get: eN 1 eN 2 1 c ; 2 D(1 c) = ; 2(1 c2 D) cD(1 c) = : 2(1 c2 D) = N (40) (41) (42) Note that, by the convexity condition of the cost function, we have 1 c2 D > 0 for all c. First, consider the case c 0. In that case, we have N ; eN 1 ; eN 2 0, and the solutions N ; eN 1 ; eN 2 are given by the terms above. Now turn to the case c < 0 and …rst consider eN 2 . Observe that p D > 1 together with c < 1= D implies 1 c > 0. Hence, for c > 0, the numerator of the fraction in equation (42) gets negative and, due to the restriction to non-negative e¤ort, the solution to eN 2 is given by the corner solution eN 2 = 0. Accordingly, for c > 0, the nonfamily manager’s expected-utility maximization problem becomes max eN 1 0 N eN 1 1 2 e 2D N 1 (43) The …rst-order condition yields eN 1 = N D: (44) The …rm owner’s expected utility maximization problem then is max ND 2 ND (45) N 1 D The …rst-order condition yields N = : This implies eN 1 = D 2 and E( N ) = 4 for c > 0. The 2 complete solution to the second-best contract in the case of hiring the nonfamily manager is summarized in equations (13), (14), (15), and (16). 13 Proof of Proposition 1 Consider the case where c > 0. Then the …rm owner’s utility di¤erence between hiring a family and a nonfamily manager becomes: E( F) E( N) = f (c > 0; ; D) = c2 ( The function f (c > 0; ; D) is positive when 1 = p 1 c+ (c 2 c 1)2 > 1, 2c(1 + ) + 1 + 4 4(1 c2 ) D(1 c2 ) (46) where 1) (c + 1) ( 4c + c2 D + 4) + c2 2 : (47) Proof of Proposition 2 For c < 0, the di¤erence of the …rm owner’s utility between hiring a family and a nonfamily manager is given by: E( F) E( N) = g(c < 0; D; ) = (1 c)2 (1 D) + (1 4(1 Dc2 )( 2 c2 2 c2 c2 )(1 c2 D) 2c + 4 ) (48) The …rm owner chooses the family manager when the above function is positive. This is the case if > 2 , where 2 = (c 1) 4 c D c2 c+ p (c2 D 1) (c + 1) (3c2 D + c3 D 4) + 2c2 D + c3 D 2 : (49) Proof of Proposition 3 We use a graphical illustration for this proof and set D = 2 for expository purpose. Note that, by the convexity condition of the cost function, we then have p12 < c < 0. The following …gure plots the function g(D = 2; c; ) for di¤erent values of c < 0 in the aforementioned range. In particular, c ranges from 0:1 to 0:6. Recall that 0 < < 1. The solid curve depicts the di¤erence in utility when c = 0:1, the dashed curve is for c = 0:3, and the dotted curve depicts the case where c = 0:6: 14 g(c,gamma) 1 -0.2 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 gamma -1 -2 -3 -4 Impact of a variation in c on g (c; D; ) As c decreases from 0:1 to 0:6, the function g(c; D; ) moves downwards. This implies that the …rm owner’s utility di¤erence E( F ) E( N ) is decreasing in the absolute value of c for any 2 (0; 1). References [1] Astrachan, J. & Jaskiewicz, P. (2008). Emotional returns and emotional costs in privately held family businesses: Advancing traditional business valuation. Family Business Review, 21(2), 139-149. [2] Bennedsen, M., Nielsen, K. M., Pérez-González, F., & Wolfenzon, D. (2007). Inside the family …rm: The role of families in succession decisions and performance. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 647-691. [3] Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gómez-Mejía, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family …rms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279. [4] Bloom, N. & Van Reenen, J. (2006). Measuring and explaining management practices across …rms and countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4), 1351-1408. [5] Burkart, M., Panunzi, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Family …rms. Journal of Finance, 58(5), 2167-2201. [6] Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family in‡uence, and family-centered non-economic goals in small …rms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267–293. [7] Chrisman, J. J., Memili, E., & Misra, K. (2013). Nonfamily managers, family …rms, and the winner’s curse: The in‡uence of noneconomic goals and bounded rationality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(5), 1103-1127. [8] Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & MoyanoFuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled …rms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106. [9] Jaskiewicz, P., Uhlenbruck, K., Balkin, D. B., & Reay, T. (2013). Is nepotism good or bad? Types of nepotism and implications for knowledge management, Family Business Review, 26(2), 121-139. 15 [10] Kets de Vries, M. (1993). The dynamics of family controlled …rm: the good and the bad news. Organizational Dynamics, 21(3), 59-71. [11] Morck, R. & Yeung, B. (2003). Agency problems in large family business groups. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 367–382. [12] Patel, P. & Cooper, D. (2014). Structural power equality between family and non-family TMT members and the performance of family …rms. Academy of Management Journal, 57(6), 1624-1649. [13] Salvato, C., Minichilli, A., & Piccarreta, R. (2012). Faster route to the CEO suite: Nepotism or managerial pro…ciency? Family Business Review, 25(2), 206-224. [14] Vandekerkhof, P., Steijvers, T., Hendriks, W., & Voordeckers, W. (in press). The e¤ect of organizational characteristics on the appointment of nonfamily managers in private family …rms: The moderating role of socioemotional wealth. 16