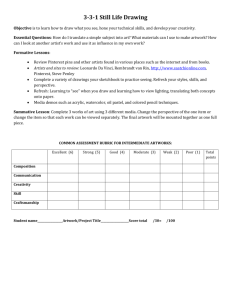

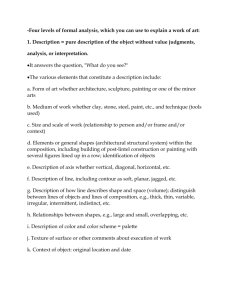

the Visual Arts Section of the Guide

advertisement