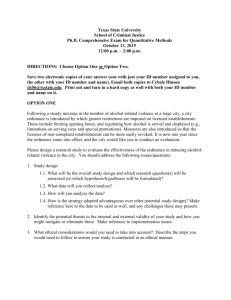

addressing the real problem of racial profiling

advertisement