Top Three Reasons to Adopt Take Note for Your Music Appreciation

advertisement

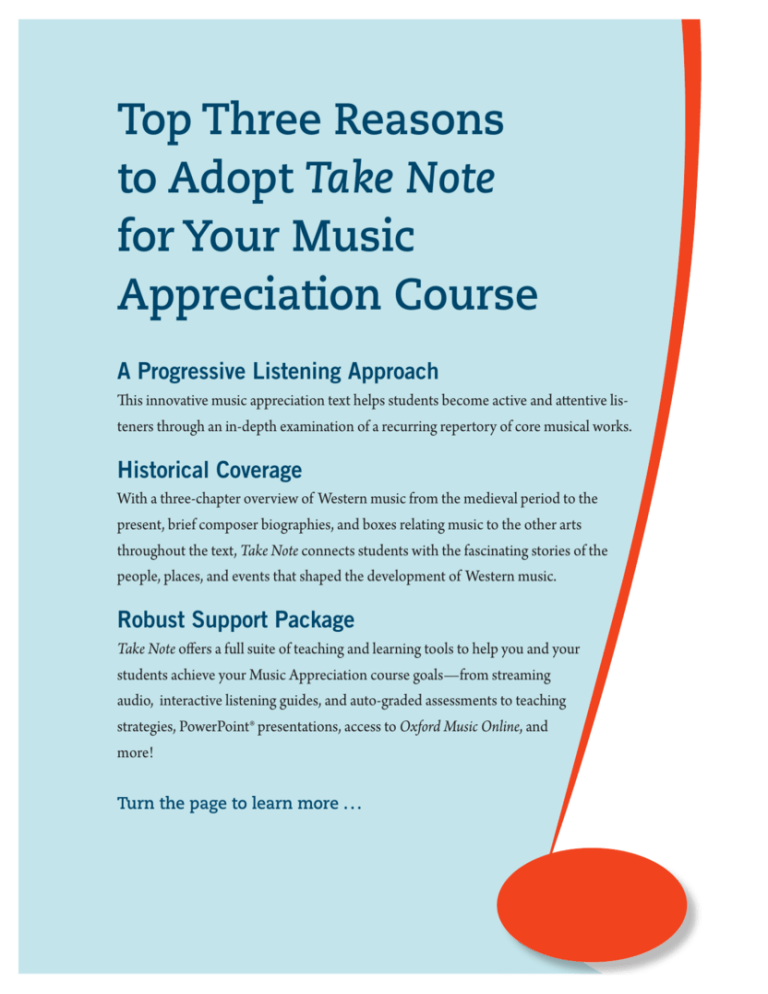

Top Three Reasons to Adopt Take Note for Your Music Appreciation Course A Progressive Listening Approach This innovative music appreciation text helps students become active and attentive listeners through an in-depth examination of a recurring repertory of core musical works. Historical Coverage With a three-chapter overview of Western music from the medieval period to the present, brief composer biographies, and boxes relating music to the other arts throughout the text, Take Note connects students with the fascinating stories of the people, places, and events that shaped the development of Western music. Robust Support Package Take Note offers a full suite of teaching and learning tools to help you and your students achieve your Music Appreciation course goals—from streaming audio, interactive listening guides, and auto-graded assessments to teaching strategies, PowerPoint® presentations, access to Oxford Music Online, and more! Turn the page to learn more . . . Progressive Listening Approach Emphasizing Core MusicalContents Works Contents in Brief v Take Note explores the elements of music through the lens of a select Contents vii group of musical works that were carefully chosen to reflect a variety Guide to the Core Repertory of Musical Works xxii of styles (piano, winds, brass, and percussion) and genres Letter from the Author xxiii (jazz, lieder, the Author xxiii world, and choral music). Starting withAbout simpler examples and progressPreface xxiv ing to more complex pieces, students will develop their listening skills Acknowledgments xxviii while getting to know these core selections. Full chapters devoted to each of the basic elements of the musical experience—form, timbre, rhythm, meter, melody, harmony, and texture—give students a deeper understanding of how all of these elements come together to make music work. Special chapters on Music in Context show how music and text are combined in Chapter vocal 9 Harmony andand Texture 235dramas. works musical ooperate. When consistent with evision, and two ct an argument. ons, which often rhaps you have eard that someat these, too, are ng that the piece e, known as the ay of explaining music on a grid, e horizontal eleo or more tones e feel increasing se are questions ether, but it perDoes each note mpanying role? ubordinate lines hod for crafting layed or sung at hey give music a n Western music he use of coun- ny will be front Chapter Objectives Define texture and harmony, and learn how their relationship has evolved through various musical periods. Distinguish between monophonic and polyphonic textures, as well as dissonance and consonance. Understand counterpoint as a significant musical development of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Recognize and distinguish between major and minor chords, and identify the way functional harmony serves as a building block for musical form. Hear how harmonic elements have evolved from the Romantic period to the present. Tonic: The main note and/or chord of a key, or of a piece written in that key. ChAPteR 1 Learning to Listen Actively 1 take Note 1 Chapter Objectives 2 Chronology of Music Discussed in this Chapter 2 Active Listening 2 The Listening Situation 2 A Core Repertory of Works 3 Key elements of Music 3 Form 4 Timbre 4 Rhythm and Meter Melody 5 Harmony 5 Texture 6 4 Music in Context 6 Music and Text 6 Music and Drama 6 Listening Practice 7 An Emotional Response to Music 7 Learning to Listen guide: Dvořák: Slavonic Dance in E minor, 72, no. 10 8 Chapter Objectivesop.open Focus On Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) 8 each chapter, providing a quick In History Dvořák’s Slavonic Dance in E minor, op. 72, no. 10 9 guide to the contents to beFrom covered Emotional to Active Listening 9 and the key ideas that students Learning to Listen guide: Mozart: Symphony no. 40 in G minor, K. 550 should learn. Focus On Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) 12 If You Liked This Music 12 Learning to Listen guide: Bach: Concerto in D minor for harpsichord and strings, BWV 1052 14 Focus On Original Instruments 15 Learning to Listen guide: Crumb: Black Angels Focus On George Crumb (b. 1929) 17 17 11 Chapter 4 The Twentieth Century and Beyond: Modernism and Jazz Learning to Listen Guides throughout the text give timed explanations of each recorded work to help students identify the basic musical elements. 97 LEARNING TO LISTEN GuIdE TAKE NOTE OF TIMBRE AND TEXTURE What to Listen For: The unusual orchestral sonorities; the often chant-like enunciation of the text. Streaming audio track 63. Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms I: Exaudi orationem date: 1930 Instrumentation: Large orchestra and four-part mixed choir Key: Variable key centers Meter: Variable meters Core Repertory Connection: Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms will be discussed again in Chapters 6 and 9. TIME ORIGINAL TExT TRANSLATION COMMENT 0:00 The introduction features the distinctive sound of Stravinsky’s orchestra, which includes two pianos. 0:34 Exaudi orationem meam, Domine Hear my prayer, O Lord 0:53 Et deprecationem meam. and give ear unto my cry; 1:03 The next phrase is sung by the full choir. A brief orchestral interlude features the oboe. 1:09 Audibus percipe lacrimas meas. 1:29 Ne sileas. 1:39 Quoniam advena ego sum apud te et peregrinus, For I am thy passing guest, Sicut omnes patres mei. a sojourner, like all my fathers. Remitte mihi, prius quam abeam et amplius non ero. Look away from me, that I may know gladness, before I depart and be no more. 2:27 The first phrase of text is sung by the altos alone. LEARNING TO LISTEN GuIdE hold not Thy peace at my The third phrase of the text is again sung by the tears! altos, followed by a resounding chord played by the full orchestra. The words “ne sileas” (“do not be silent”) are sung by the altos and basses with a faster-moving accompaniment. The accompaniment slows down again for the next two phrases, which are sung first by the altos and basses and then by the full choir. At the word “mei,” the orchestra becomes noticeably louder and more active. From this point on, the choir sings continuously, Chapter 9 Harmony and Texture although the texture of the orchestral accompaniment shifts several times. 253 Ps. 39: 12–13 (RSV) Online interactive listening guides available anything a 20th-century composition, just as there is no chance of mistaking The lack of harmonic resolution, which makes this What to Listen For:but a skyscraper for a cathedral spire. The short, detached chords at the opening, the music sound restless and unsettled. on the book’s Dashboard website percussive timbres of the pianos used in combination with the orchestral winds, Streaming audio track 51. dissonant the sudden shifts and changes heard throughout the Wagner: Tristanthe und Isolde,harmonies, Prelude, and beginning combine a visual representation piece all mark it as a product of its own time. date: 1859 of key works with running comInstrumentation: Large orchestra Key: A minor Meter: 6 (two slowly moving groups of three beats per measure) mentary to help students follow 8 along in real time while they TIME PROGRESSION COMMENT listen the bymusic. 0:00 Opening motive The motive representing Tristanto is stated the cello, with the winds adding TAKE NOTE OF MELODY AND HARMONY 04-Wallace-Chap04.indd 97 05/12/13 1:32 PM the harmonies that make up the famous “Tristan chord” progression. If You Liked This Music boxes encourage students to expand their playlists and listening skills beyond the core repertory by offering additional listening suggestions throughout the text. 0:21 Repetition The opening is repeated at a higher pitch. 0:41 Repetition and continuation It is repeated on yet a higher pitch and then extended. 1:35 Love theme The theme representing the love between Tristan and Isolde is played by the cellos. This is the first music heard so far that can be played on the white keys alone. If You Liked This Music . . . A Quick Listen to Wagner Wagner’s operas are long and daunting, but for a quick glimpse at his dramatic genius, the following are recommended: • Wotan’s Farewell from Die Walküre—The scene in which the king of the gods leaves his daughter Brünnhilde defenseless except for the ring of magic fire with which he surrounds her is deeply affecting, especially if you listen to the duet that precedes it (approximately the last 40 minutes of Act III). • The song contest from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. The conclusion of Act III of Wagner’s only mature comic opera contrasts Walther von Stolzing’s stunning prize song with a very funny misreading of it by his rival Beckmesser. • The Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde—Isolde’s “love death,” with which the opera concludes, is frequently paired with the prelude in performance. • After listening to these examples, you might also consider watching the Star Wars movies and paying particular attention to John Williams’s music. Williams deliberately imitated many of Wagner’s techniques, particularly the use of pregnant motives to represent characters and ideas in the plot. In technical terms, the harmony now contains more dissonance than consonance. Traditional musical syntax dictates that a dissonant chord be followed by a consonant one. To follow a dissonance with another dissonance, and then another— as Wagner does here—is like writing a sentence consisting almost entirely of verbs. Historical Coverage In order for students to fully appreciate and understand music, Take Note contains numerous chapters and features that explore the development of Western music over time. 266 Part 3 Bringing It All Together Chapters 2, 3, and 4 provide an overview of Western music from the Medieval period to the present. Chapter Objectives Describe the different ways music and text can work together. Consider what happens when a composer makes the text deliberately hard to understand, or when the music seems to subvert the text. Chapter 3 Distinguish among Classical and semantic, Romantic Music phonetic, and syntactic qualities of text, and understand how they may all Compositions from the Classical and Romantic periods illustrate the major be reflected a musical tendencies of classical music to create aesthetically pleasingin and expressive music. Although the historical period known as Romanticism ended long setting. ago, it continues to influence the culture and style of our time. Take NoTe Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (ca. 1525–1594) Chapter Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque Music 2 Indicate how music can suggest meanings that are less evident when one simply reads the words. In this chapter we will examine the historical periods in music commonly called Classical and Romantic, which roughly correspond to the late 18th and 19th centuries. Works from these periods still form the heart of the repertory performed by most classical musicians. There is also no clear dividing line between them, which is why Beethoven is often considered a part of both periods. 62 Take NoTe Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) History is a silent but supportive partner in the active listening process. Compositions from the Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods lay the back- 03-Wallace-Chap03.indd 62 ground for what has come to be the standard repertory of classical music. Although the performance of music always takes place in the present, music also represents the time in which it was created. This makes history another enormously important topic in the understanding of music. Knowing the factors that influence the creation of music—whether cultural, economic, technological, religious, or political—provides another dimension to one’s exploration of music. History is a silent but supportive partner in the active listening process. 33 to as the text. In opera, the lyrics are spoken text and words to be sung (se When music has words, the active tions. What is the relationship betw composer have for combining these the text? Is it possible for music and How might the skillful combinatio more effectively than either of these In this chapter, we will see how te in our mind and arouse emotional re spond to the sounds and structure o tion of the text’s meaning, perhaps b techniques were common in the Rom art song. Therefore, we will concent also looking at some music from oth music with text may challenge our ex Fitting Music and Some music is so elaborate that the t think of a well-known song in whic In many cases, the music also enhan Modernism and Jazz nique commonly known as text pai Little Star, for example, the phrase “u begins on a high note before it descen Chronology of Music melodic jump at the opening also i Discussed in this Chapter ascends far above the note it started manner that resembles an inverted Mid-14th century Guillaume de Machaut p. 271 painting upside down by having the Lasse! comment oublieray/Se indicated by the text. When Johnny C j’aim mon loyal/Pour quoy me bat mes maris?, motet in Ring of Fire, the notes are rising, notes dropping down. 1828 Franz Schubert p. 266, 280 Creating a purposeful connectio Winterreise: Der Lindenbaum; many art songs from the Romantic p Die Post; Der Leiermann work from the classical music reperto 1840 often provides a musical setting for a Robert Schumann cally feature a singer and piano acco Dichterliebe: Ich grolle nicht, p. 278; Die alten, bösen Lieder crucial role in reinforcing and interp p. 282 Chapter 05/12/13 12:39 PM Recognize the different The Twentieth voices (personas) from which Century Beyond: music texts can be and interpreted. 4 Take NoTe In the Modern period, the musical mainstream moved away from Western Timelines and Chronologies of Works place selections and key developments in music history in the context of world history. 02-Wallace-Chap02.indd 33 05/12/13 12:35 PM 64 Timeline 3.1 The ClassiCal era (1750–1825) World evenTs MusiCal MilesTones Christoph Willibald Gluck (Bohemian/Austrian—1714–87) Joseph Haydn (Austrian—1732–1809) Johann Stamitz named director of instrumental music at Mannheim, home of the first modern symphonic orchestra (1750) 1750 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian—1756–1791) James Watt improves the design of the steam engine (1765) Ludwig van Beethoven (German/Austrian—1770–1827) American and French Revolutions (1776–89) Eli Whitney invents the cotton gin (1793) First documented performance of an opera in America, in New Orleans (1796) Napoleon is Emperor of France (1804–15) Robert Fulton invents practical steamboat (1807) Congress of Vienna (1815) The War of 1812 between the United States and United Kingdom (1812–15) 1800 American popular music rose to assert itself as a major counterforce to the European classical tradition. Works of jazz provide an excellent listening example for exploring the basic elements of music. 91 04-Wallace-Chap04.indd 91 Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (German—1714–1788) Seven Years War in Europe (1756–63) Europe to encompass composers from Eastern Europe and America. 1938–1941 Luigi Dallapiccola p. 284 Canti di prigionia (3 movements). 05/12/13 1:31 PM Schubert: Winterreise, D We have already examined one song an example of modified strophic for songs, was written by Wilhelm Müll of Schubert. Despite the text’s predi Müller’s imagery to create vivid em musical images, and Schubert’s mu Chapter 3 Classical and Romantic Music Clear and vivid maps help students connect each musical piece and artist with places around the world. 65 Baltic Sea North Sea Chapter 4 The Twentieth Century and Beyond: Modernism and Jazz 101 GERMANY Weimar Focus On boxes draw from Oxford’s own distinguished Grove Music Online reference site to offer students concise background information on composers and other music-related topics. Students who purchase a new copy of Take Note will have access to the entire contents of Grove Music Online within Oxford Music Online. Across the Arts boxes examine parallels between music and the other arts, allowing students to discover what music has in common with poetry, storytelling, painting, architecture, and drama. 200 Part 2 Listening Through Musical Elements Across the Arts The Medieval Worldview Focus On Erasbach Erasbac Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Salzburg French composer. One of the most important musicians of his time, his harmonic innovations had a profound influence on generations of Bay of Biscay composers. He made a decisive move away from Wagnerism in his only complete opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, and in his works for piano and for orchestra he created new genres and revealed a range of timbre and color that indicated a highly original musical aesthetic. (François Lesure and Roy Howat, Grove Music Online.) Vienna Rohrau AUSTRIA Claude Debussy (1862–1918). Debussy composed many volumes of colorful and evocative music for piano, as well as ensemble and vocal music. Adriatic Sea Grove Music Online. (© adoc-photos/Lebrecht Music & Arts) In 1948, 30 years after the death of Claude Debussy, American composer Virgil Thomson wrote, “Modern music, the full flower of it, the achievement rather than the hope, stems from Debussy. Everybody who wrote before him is just an ancestor and belongs to another time. Debussy belongs to ours.” Thomson’s essential insight still applies today. All great composers have broken rules, but Debussy was one of the few who have been able to reinvent the language of music. Like the Impressionist painters to whom he is often compared, he worked with colors, 272 Part 3 Bringing It All Together both instrumental and Musical harmonic, inElements ways that defied traditional of the Classical Repertory expectations. While hisWhile music has become it for hasitsnot lost Baroque music is“classical,” often known ornamental complexity, Classical music its edge; it still surprises us.straightforward, at least on the surface. On closer hearing, all canand be delights disarmingly Aegean Sea Composers of the Classical Era. Map 3.1 In History is not always as it seems. Classical forms may be clear and easily followed, but Classical composers delight in surprising the listener. You can expect to hear lots of short-term contrast andSchubert’s change in this Winterreise music, especially when compared to that of the Baroque. You mayWinterreise hear “flashes” of instrumental changes (Winter’s Journey),color; written only in timbre, or tone color, are one of the ways in which Classical composers to add interest months before Schubert’s death inlike 1828, was and complexity to their music. As a piece progresses, a richer timbre may signal the second of his two genuine song cycles. an expressive high point. So mayit aand more complex or unexpected harmonic Both the earliertexture Die Schöne Müllerin (The changes. Beautiful Maid of the Mill) deal with unrequited love, one of the favorite subjects of the Romantics. They both consist of settings of a series of poems told from the point of view of a rejected lover and implicitly ending with his death. Winterreise, however, is particularly severe. The lover has already been rejected when the cycle begins, and his love is 03-Wallace-Chap03.indd 65 described only in retrospect. The images in the poetry are unrelentingly somber, and Schubert’s music follows suit. Landscape at Vétheuil, c. 1890, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. This painting by the French It is something of a cliché to say that this impressionist master shows the same experimentation with color effects and blurring subject is an expression of the alienation and of traditional lines that are widely associated with Debussy’s music. (Ailsa Mellon Bruce loneliness so frequently expressed in modern Collection) art of all kinds. In fact, similar images of isolation from a beloved occur in the troubadour poetry of the late Middle Ages. These songs can be linked in many ways, however, to their historical moment. One is their abundance of nature images, including the linden tree with its rustling leaves and the fierce winter wind. In his 101 poems, Müller treats nature as a place to escape the pressures of modern urban life. Readers of English literature often find this theme in the writing of the early Romantics, such as the poetry of William Wordsworth. Rest as a metaphor for death and release was also a favorite theme of the Romantics. In Ode to a Nightingale, for example, John Keats yearns “to cease upon the midnight with no pain,” much as Schubert’s singer-hero longs to lie down beneath the tree and its sheltering branches. The idea of the rootless wanderer as a heroic figure is also typical of Schubert’s time; his own The rhythm of Lasse! comment oublieray/Se j’aim mon loyal/Pour quoy me bat mes maris? is difficult for us to understand, but it made perfect sense to medieval listeners. In the medieval worldview, the universe itself was built in interlocking layers, thought to operate according to musical proportions. If you have trouble perceiving Machaut’s rhythms, consider that the proportions of the universe cannot be seen or heard 04-Wallace-Chap04.indd either, at least in ordinary terms. Yet in the medieval cosmology they dictate the terms on which life is lived in the visible world. In this photo, Music is personified in the panels on the left, while the panels on the right illustrate the three levels of the musical universe. On top is musica mundana, better known as the “music of the spheres,” showing that the universe is constructed according to musical proportions. In the middle is musica humana, the “music of human life.” Musica instrumentalis, sounding music, appears only in the bottom panel, and the female figure of Music points at it reprovingly, as though to remind it that it is only a pale imitation of the higher levels. This view of music was most notably expressed by Boethius (ca. 480–524), the late Roman philosopher who also provided the text for the second movement of Dallapiccola’s Canti di prigionia. Though it was based on ideas from the ancient world, This famous illustration shows the medieval view of the world Boethius’s musical worldview helped to define as consisting of three different kinds of music. (© Lebrecht Music and Arts) the way the universe was understood for centuries after his death. 06/12/13 1:39 PM Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840). Restlessness, longing, and the power of nature were primary of the Romantic spirit. (bpk/Berlin, 05/12/13 1:33components PM Art Resource, NY) song The Wanderer served as the basis of one of his most famous piano works, the Wanderer Fantasy. German artists such as Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) often depicted this figure as well. So if there is such a thing as the Zeitgeist, or “spirit of the times,” these songs convey it in a particularly poignant and powerful way. Schubert’s music, which does so much to amplify Müller’s texts, is a uniquely suitable vehicle for the outlook of the Romantic period. In History boxes discuss the greater cultural and social contexts of key works in history, compelling students to think beyond the music. 10-Wallace-Chap10.indd 272 Most later music also has multiple rhythmic layers, even if they are not as predictable as Machaut’s. In Dvořák’s Slavonic Dance, for example, the measures are grouped in pairs, and the pairs of measures are grouped in pairs as well, as are the pairs of pairs, resulting in regular phrases (a term used to describe musical thoughts, which are much like phrases in language) of four and eight measures and even regular groups of such phrases. Such large-scale metrical patterns are Robust Support Package www.oup.com/us/wallace serves as the gateway to everything that you and your students will need for your Music Appreciation course. Dashboard for Take Note Streaming audio, interactive listening guides, musical instrument videos, and a wealth of additional resources for Take Note are available in Dashboard by Oxford University Press. Dashboard delivers quality content, tools, and assessments to track student progress in an intuitive, web-based learning environment. A streamlined interface connects instructors and students with the functions that they perform the most and simplifies the learning experience by putting student progress first. Interactive Listening Guides and Streaming Audio put students in full control of the listening experience. Interactive listening guides combine a visual representation of key works with running commentary to help students follow along in real time while they listen to the music. Additionally, all of the audio examples discussed in the text are available in streaming audio format. • Discover View offers an overview of the piece, including the basic structure of each section. • Listen Closely View displays all the information about the piece, including the melodic “shape” for each instrument so that students can follow the music as it unfolds. Auto-graded assessments allow instructors to easily check students’ progress as they complete their assignments. The color-coded gradebook illustrates students’ strengths and weaknesses at a glance, allowing instructors to adapt their lectures to student needs. Instrument videos bring individual pieces of the orchestra to life, giving students a closer look at the instruments and actions behind what they hear. A bonus, online Chapter 13, “Actively Listening to Additional Works,” is available for students who would like to practice active listening skills on additional works. Access to Dashboard can be packaged with the text at a discount (978-0-19-938588-1), stocked separately by your college bookstore (978-0-19-934282-2), or purchased directly at www.oup.com/us/wallace. Actively Listening to Additional Works Special Supplement to Take Note by Robin Wallace Bonus Online Chapter 13 Th is bonus chapter provides supplementary listening activities for Take Note by Robin Wallace. It is only available online from the Take Note companion website. It is provided for those students and instructors who would like to practice active listening skills on additional works. Th is chapter introduces four major works spanning Medieval to Modern music. TAKE NOTE Active listening skills can be applied to any musical experience. Draw upon the fundamental elements of music to appreciate familiar and unfamiliar works. Take Note Bonus Online Chapter 13, Actively Listening to Additional Works © 2014 Oxford University Press USA 13-Wallace-Chap13.indd 1 W1 31/10/13 3:05 PM Robust Support Package Oxford Music Online A free 12-month subscription to Oxford Music Online is included for students with all new copies of this text. Within Oxford Music Online, students will have access to Grove Music Online, the leading online resource for music research with thousands of articles to search or browse. Throughout Take Note, you and your students will find reference to specific articles in Grove that offer more in-depth information on the topics covered in the text. Additional Teaching Tools Instructor’s Manual, PowerPoint Slides, and Test Bank are available online (www.oup.com/us/wallace) or on CD. Instructors who adopt Take Note will be given an access code allowing them to view the instructor’s manual for the text, which features chapter summaries, teaching strategies, sample test and essay questions, sample in-class and assignable activities, and links to websites featuring related materials. In addition, a downloadable set of PowerPoint ® slides is offered to accompany in-class lectures or for posting on class websites for student review. An automated test bank, that can be used to create custom exams, is available to adopters. Questions can be edited or rewritten, and additional questions can be added to the bank. An ebook is available through CourseSmart © (www.coursesmart.com) Visit www.oup.com/us/wallace for links to and additional information on all of these resources for Take Note.