Volume) Journal of Hand Surgery (British and European

advertisement

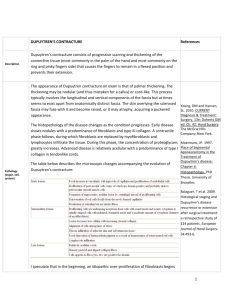

Journal of Hand Surgery (British and European Volume) http://jhs.sagepub.com/ The Early History of Contracture of the Palmar Fascia : Part 1: The origin of the disease: the curse of the MacCrimmons: the hand of benediction: Cline's contracture D. ELLIOT J Hand Surg [Br] 1988 13: 246 DOI: 10.1016/0266-7681(88)90078-2 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jhs.sagepub.com/content/13/3/246 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: British Society for Surgery of the Hand Federation of the European Societies for Surgery of the Hand Additional services and information for Journal of Hand Surgery (British and European Volume) can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jhs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jhs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://jhs.sagepub.com/content/13/3/246.refs.html Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 THE EARLY HISTORY OF CONTRACTURE OF THE PALMAR FASCIA Part 1: The origin of the disease: the curse of the MacCrimmons: the hand of benediction: Cline’s contracture D. ELLIOT From the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle-upon-Tyne The earliest reference in surgical history to the contracture of the palmar fascia which has become known as “Dupuytren’s disease” is in the writings of Felix Plater of Base1 in 1614. In the third volume of his Observations, he described the case of a stone-mason with this conditon (Fig. 1): the irrevocable drawing into the palm of the hand of the ring and little fingers and ridging of the palmar skin is pathognomonic. Plater’s stone-mason, like many patients since, associated the onset of the disease with a specific traumatic event, though the relative timing of this injury and the onset of the contracture are not recorded. Plater believed the tendons to have contracted and pulled out of their sheaths, so raising the palmar skin in ridges as they bowstringed across the palm, an interpretative error which was to persist for 200 years. It is surprising that no earlier reference to this condition has been found in the Scandinavian literature or in that of their subject races, since it has been suggested that the disease originated in North Europe. In Great Britain, this view is supported by the apparently high incidence of the condition today in those parts of the country which faced the Norsemen, namely north-east England and the north and west of Scotland both of which were invaded and subsequently colonised, the former permanently and the latter for nearly 500 years. Nothing of relevance has come to light in the archeological investigation of Fig. 1 Plater’s description of Dupuytren’s contracture, 1614. CONTRACTION OF THE FINGERS OF THE LEFT HAND INTO THE PALM. A certain well-known master mason, on rolling a large stone, caused the tendons to the ring and little fingers in the palm of the left hand to cease to function. They contracted and in so doing were loosed from the bonds by which they are held and became raised up, as two cords forming a ridge under the skin. These two fingers will remain contracted and drawn in forever. Translation by J. B. St. Clair, 1987. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine). r4p IN Mo~vs IMPBTENTI~ vitaeT;.j. Styracis 3, ij. Laricez 3.n. Cerz q.Cfiat vnguen turn. Man&dein fepofitk emplalttis,fomentatio hat adhibebatur: R.rad.Althele,Bryonia,lreos,Lilio. rum 4 recentium, inciforum, de fingulis quantum p&lum vulgare caperet, Abfynthij, Thymi,Saluiz an.M.j.Aor.Ch~morn,Meli~~.Sambuci an.P.j. feminumLiui,Focnog.ao.coch~~.vel quatuor,coz quaotur in deco&.2ointefiinorum Capitis & pe. dutnvituli, addita pauco Vine : Atquein deco&o manusfoueat hgulis matutinis. Interea licet omnia in melius tenderent,fpesri; jntegra5 ri$itutionis The Royal Victoria Infumary, tame0, quia tempus Nfignis artifex lapicida quidam,faxumimmenfum voluer,s, aded tendines in finif& maaus vola ad digitor, annularem & minimum definew tes, ei attra&i runt, vt illi h vinculis quib.retinErur laxati, rleuati+e, duaschordas fib cute ten& in alwn referrent, contrafii4ue duo hi digiti S; at- I tra&i,poReahnpcr Received: 12 April 1988 Mr. D. Elliot, F.R.C.S., upon-Tyne, NE1 4LP effh, pr&wm aderat , thermas difiantes procul, ma. gno Iabore & fumptu, lacp & alp&us iuperatis, adijt. Quorum vfu, digitiamphtis akingi potitis relaxari caeperunt. Et c&min reditu lacum num, naui traijceret, tanta vertigine car. e@,cum vomicu ab initio, vt necaare net GAerepoffet , fed le&ichve&us ad nos,indeG; do. mum duceretur. Vnde manus iterum relblutat lint. @arum curam poRea defperans, cdm etim puderet,denuci meovti confilio,cuinonadfineln uCqueparuerat,neglexit. manferint. Queen Victoria Road, Newcastle- 2A6 THE Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 JOURNAL OF HAND SURGERY REVIEW ARTICLE: THE EARLY HISTORY OF CONTRACTURE Hadrian’s wall (stretching across the northern border of England) to suggest that it was the Romans, and not the North Europeans, who brought this disease to northeast England. However, the Anglo-Saxon medical writings available to us make no mention of the condition, though the monks recorded treatments for other hand conditions and of some recognisable diseases of the skin and superficial tissues. The omission of any reference to contracture of the palmar fascia may simply be a result of the fragmentary nature of the record which has survived. When life expectancy was short, by comparison with today, the incidence of this disease of late middle and old age may have been small and the disease considered comparatively trivial. Had it affected a younger age group, one might have expected more medical interest and, possibly, discussion of it in the social literature, as flexion contracture of the fingers would have been more than a little inconvenient to fighting men. The prevalence of the disease in the Western Isles of Scotland is acknowledged in the legendary “Curse of the MacCrimmons”. The MacCrimmons held land from the clan MacLeod of Skye (themselves of Norse descent) and were musicians to the chieftains of this clan. They were recognised to be pre-eminent among players of the bagpipes. At the end of the 15th century, the 8th chief of MacLeod endowed a college of piping on Skye under the tutelage of the MacCrimmons and, for the next 300 years, the chiefs of the Highland clans sent their young pipers to Skye for periods of several years to perfect their skills. Much of the ancient pibroch music which has survived to the present time came from this school and was composed by the MacCrimmons. The MacCrimmons were believed to have been cursed with a condition which bent the little finger - the socalled “cruimein curse” - making the playing of the bagpipes impossible, for the little finger of the right hand is singularly important in playing this instrument. It is assumed that this curse must have been Dupuytren’s disease, and not camptodactyly, since it affected accomplished, and therefore mature, adult pipers. The origin of the family and of the curse are lost in the mists of time and no member of the clan now survives. The available records in the Scottish National Library contain no factual evidence that any of the major figures in the clan suffered from this curse. However, these records are also fragmentary in that they only detail the lives of the best pipers of the family, for the best piper of each generation would have been selected as head of the family (in accordance with the Celtic principle of Tanistry, whereby the successor to this position was chosen by family election and not by descent). In a society in which Dupuytren’s disease was, and is, common and in which pipers stood second only to the chieftain (a relationship which altered only after the defeat of the Jacobites at Culloden, when the VOL. 13-B No. 3 AUGUST OF THE ?ALMAR FASCiA Heritable Jurisdiction Abolition Act of 1747, introduced to abolish the clan system, degraded pipers “to the level of ordinary musicians”), it is understandable that affliction of these men, with the associated loss of their prestigious position, would have been a matter of some note. The incidence of the disease among pipers would have become correspondingly magnified in the eyes of the local populace. Just as all the pipers of the MacCrimmon family were unlikely to have escaped the condition (by virtue of their ancestry), many of today’s pipers have been similarly afflicted and Dupuytren’s disease remains common among pipers, to whom it is still known as the “Curse of the MacCrimmons”. However, there is no evidence that they are more prone to this disease than any other of their clansmen. Another interesting but unsubstantiated relationship is that of the hand of benediction and Dupuytren’s disease. Illustrations of Dupuytren’s disease by the hand of a saint are common: La Main de ieu from the church of San Clement de Taul, in Catalonia, adorns the most recent version of the G.E.M. monograph and the Manus Apostolicus from the monastery of San Bruno, in Terassa, Spain, illustrated an article by Dr. Juli Bruner on Dupuytren’s disease in 7% Hand in 1970. recent discussion of this subject by Dr. Redfern (1986), in a correspondence newsletter of the Ameri.can Society for Surgery for the Hand, dismissed the suggestion that an early Pope who suffered from Dupuytren’s disease might, by force of character, have stamped his own disability on the church for all time. She explained how the raised hand of benediction is represented differently in the Western and Eastern traditions of Christian art, the Greek form being more explicit in that the fingers are held in the position of the letters IC XC, abbreviated from IHCOYC XPICTOC or Jesus Christos. The Latin form is less easily explained. She supports the theory that its origin is much older than Christianity, and probably represents the superimposition of a oman gesture, from earlier times, on the Christian church, with the adoption of this religion by the Empire in the 4th century. This view is reinforced by a 4th century representation of Pope Xystus II (257-258 A.D.) on a gold glass, in the Museo Sacro in the Vatican: the Pope faces another man called Timotheus whose hand is held in the position of benediction, indicating that the symbolic gesture was already in use at this early stage in Church history. When this ornament was made, the Church of Rome had barely survived the most systematic attempt to destroy Christianity which the Roman state ever mounted, namely the persecution of the emperors Decius, Aurelian and Diocletian (Xystus himself was executed with the whole diaconal college in August 258). The bishops of Rome were struggling to gain ascendancy over the great eastern sees of Antioch and Alexandria: the period seems an unlikely setting for 1988 247 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 D. ELLIOT the origin of religious symbolism. The temporal power of the papacy only became a significant feature in European politics from the reign of Gregory I (590-604) and the imperialistic Popes, such as Gregory VII (1073-1085), Innocent III (1198-1216) and Boniface VIII (1294-1304), were many centuries too late to have imposed any deformity of the hand which they might have suffered upon the Church. A further feature of the hand of benediction which makes the Dupuytren’s disease theory of origin unlikely is the great variation of hand postures recorded in religious art throughout the ages: the exact positions of the ring and little fingers differ considerably, as can be seen in the illustrations mentioned above and by examination. of other early ecclesiastical statues and paintings. For example, the dominant hand posture of many of the statues in the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris is more like the clawed hand of ulnar palsy than that of Dupuytren’s disease. In contrast, the blessing of the present Pope is given with an open hand held sideways to the audience, with very little exaggeration of flexion of the little and ring fingers. Whatever the truth, it enhances the association that a statue of a saint, with his hand held appropriately, adorns the church which has replaced the house in the Place du Louvre which was occupied by Dupuytren during the latter part of his professional life. The advent in Europe of the anatomist-surgeons of the late 18th century sparked a revolution in surgery. What had happened before is reflected in Cruveilhier’s criticism of their predecessors as having seen many diseased people but almost no diseases. The massive determination of the new men to explain their observations of both normal and abnormal bodily functions by morbid dissection is the foundation of modern surgery. Foremost among these were the Hunter brothers, and John Hunter is considered to be the father of British surgery. Surprisingly, the voluminous works of the Hunters contain few preparations of diseased hands and none of contraction of the palmar fascia. However, it was one of John Hunter’s pupils, Henry Cline senior, who first dissected a hand with this condition in 1777 and described its treatment by palmar fasciotomy soon after. Though little-known today, Henry Cline was a prominent medical figure in London in his time. He was born in 1750 and was apprenticed at the age of 17 to Thomas Smith, surgeon to St. Thomas’s Hospital. On the death of Thomas Else in 1781, Cline was appointed Lecturer in Anatomy and Surgery to the hospital. Three years later, he succeeded Smith as consulting surgeon to St. Thomas’s. Cline dominated this hospital for 30 years, at a time when it was predominant among the London hospitals, and his teaching played an important part in the spread of the new discipline of surgery throughout England. In 1811, at the age of 61, he retired from his teaching appointment and, in the following year, resigned his clinical post in favour of his son. Having been appointed to the Court of Assistants of the Surgical Company in 1796, he continued to serve on the Court of the new College of Surgeons of England from its inception in 1800. He was a member of the Court of Examiners in 1810 and Master of the College in 1814. He served as President of the College in 1823 (the title of Master having been changed to that of President in 1821). He delivered the Hunterian orations in 1816 and again in 1824. He died in 1826 at the age of 76. Cline senior was a fervent supporter of John Hunter at a time when the surgeons of London mostly considered the latter’s manners uncouth, his speech archaic and his lectures boring. Cline had scant respect for Else, his predecessor in St. Thomas’s, and is reputed to have said, on first hearing Else lecture, that “he thought he should soon be able to do better than that”. By contrast, after attending Hunter’s first course of lectures in 1775, Cline wrote: “Having heard Mr. Hunter’s lectures on the subject of disease, I found them so far superior to everything I had conceived or heard before, that there seemed no comparison between the great mind of the man who delivered them and all who had gone before him.” Whether this respect was mutual is not recorded. An anecdote related by Palmer, in his Works of John Hunter, F. R. S. (1835), says something of their very different temperaments: “The late Mr. Cline once excited his [Hunter’s] ire by an offence of this kind. He had engaged Hunter to meet him in consultation on a case in the afternoon, but in the course of his morning rounds saw another patient, respecting whom he wished to take Hunter’s opinion, and accordingly, without giving him previous notice, appointed to call with him after the former engagement was ended. When the first visit was over, Cline mentioned the second appointment, on hearing of which Hunter got into a towering passion, and asserted that Cline had acted in the most unjustifiable manner in thus deranging the whole of his arrangements for the afternoon.” Though Cline’s contribution to the expansion of surgery in his time was by no means modest, perhaps his most lasting influence on the development of the speciality in England was as a link between John Hunter and Astley Cooper. In 1784, the wayward Cooper was sent by his parents, who despaired of his ever settling to any profession, to his uncle, William Cooper, then senior surgeon of Guy’s Hospital. At the time Guy’s and St. Thomas’s hospitals were closely associated (and were known as the “United Borough Hospitals” or the “United Hospitals”) and William Cooper lodged his nephew with Cline, newly appointed to the staff of St. THE JOURNAL OF HAND SURGERY 248 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 REVIEW ARTICLE: THE EARLY HISTORY OF CONTRACTURE OF THE PALMAR FASCIA Thornas’s. The younger Cooper quickly caught Cline’s enthusiasm for anatomy, surgery, and for John Hunter. He established a pace of work, both in the clinical practice of surgery and in anatomical research, which, continuing as it did for nearly 60 years, until shortly before his death in 1841, was phenomenal. What Hunter lacked in good manners and as an orator, the handsome and pleasant Cooper possessed in abundance. His industry and gift of communication were to extend and spread Hunter’s work and philosophy in a manner of which the dour Scot had himself been incapable. In 1789, after an apprenticeship of five years, Cooper was invited by Cline to share his lectures. This partnership dominated surgical teaching in London for 22 years and, on the retirement of Cline in 1811, Cooper continued to lecture with Cline’s son until the premature death of the latter in 1820. However, Henry Cline junior was a poor substitute for his father and was said to have been a shy, sickly man and a monotonous lecturer. Cooper frequently paid tribute to his teacher as the origin of ideas which he, Cooper, popularised. He dedicated his celebrated treatise on hernias to his “Master in Surgery, Henry Cline” and asked that Cline assist him in performing the operation on King George IV of England for which he himself was knighted. The King is reputed to have said “Well, I respect Cline and I dare say he respects me, although we do not set our horses together in politics”; (Cline was well-known to have Republican leanings at a time when sympathy with the new regime in France would not have found favour in English court circles). Cooper is said to have graciously handed the scalpel to the older surgeon to complete the operation: Cooper’s own description is slightly less gracious, “On the side on which Cline stood I begged him to detach it which he did but it took up a great deal of time on the whole”, and indicates a degree of irritation which is inconsistent with Cooper’s image in history and suggests that he had forgotten that Cline was, by now, 71 years old and had been retired from clinical practice for ten years! Sadly, the controversy which led to the split of the United Hospitals (which was precipitated by a difference of opinion over the appointment of Cooper’s successor) also led to the estrangement of these two great friends. Though Cooper was eventually to eclipse his mentor and Cline’s name has submerged beneath those of Hunter and Cooper, it was nevertheless Cline who first recognised the true nature of the condition now known as Dupuytren’s disease. In 1777, by coincidence the year of Dupuytren’s birth, he dissected two cadaveric hands with this contracture of the fingers. The entry in his note-book (Fig. 2) records the involvement of the palmar fascia and the effect of dividing it. He recognised the disease as one of “laborious people”. In one of his dissections, the disease involved all the fingers. The record of his long career as a lecturer in anatomy and surgery is fragmentary and the earliest indication that his observations were passed. on to his students are the lecture notes of Thomas Smart in 1787 (Fig. 3): here, Cline proposed an operative cure (by palmar fasciotomy) though he had not performed the procedure at this time. Smart also records Cline’s description of traumatic cure of the disease by sudden extension of the fingers. This has subsequently been reported “for the first time” on two occasions: in 1879 by William Adams, the leading figure in the surgery of Dupuytren’s disease in the second half of the 19th and much more recently by Grace, century, McGrouther and Phillips (1984). Only a few of the preserved notes from the Cline/Cooper lectures of the period 17841811 mention the finger contracture and then only as an aside in a lecture series which, though expanding each year, was a fairly standardised course of anatomy and surgery, Having recognised the nature of the disorder and devised a treatment for it, their discussion of it is dismissive, suggesting that it was little more than a curiosity in their clinical practice. Thus, the lecture notes of John Windsor, who came to London from Manchester to learn his trade from the surgeons of the United Hospitals and from Abernethy of Rarts. and later returned to his native city as a surgeon to the Eye Hospital, described the state of the art in 1808. After a brief description of the anatomy of the palmar fascia, the lecturer, Henry Cline junior, comments that: “One or more of these tendinous columns of the aponeurosis palmaris sometimes becomes contracted and thickened; most generally one only but sometimes more, and is affected, proportionally so many fingers are bent into the palm of the hand. The treatment is easy and efficacious; it consists in cutting through the aponeurosis with a common knife. In performing the operation, carefully dissect through, fibre by fibre, the aponeurosis palmaris, in order to avoid the blood-vessels and nerves beneath; the finger or fingers may be kept extended afterwar splint, for the flexor muscle has in some degree become shortened, and without this the disease might be reproduced.” There follows a brief discussion of the differential diagnosis from Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture. Cline echoes Plater’s description of the stone-mason’s hand, reiterating what is the clinical hallmark of Dupuytren’s disease: “. . . the latter (aponeurosis palmaris) feels like a very hard cord raising the skin.. .” He then adds “... but the flexor are too low to start thus, and are also bound down by the ligamenturn annulare”, so excluding the flexor tendons from further involvement in this disease in England. Cooper, writing again of this condition in 1822, was equally brief, but, perhaps, considerably more astute VOL. 13-B No. 3 AUGUST 1988 249 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 D. ELLIOT Fig. 2 Henry CIine’s note-book, 1777. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Library of St. Thomas’ Hospital Medical School, London). than has been realised. In a chapter on dislocations of the fingers and toes in his book A Treatise on Dislocations and Fractures of the Joints, Cooper wrote: “The fingers are sometimes contracted in a similar manner (he had been discussing the treatment of hammer toes) by a chronic inflammation of the thecae (the flexor tendon sheaths) and aponeurosis of the palm of the hand, from excessive action of the hand, in the use of the hammer, the oar, ploughing, etc. etc... When the thecae is contracted, nothing should be attempted for the patient’s relief, as no operation or other means will succeed; but when the aponeurosis is the cause of the contraction, and the contracted band is narrow, it may be with advantage divided by a pointed bistory, introduced through a very small wound in the integument. The finger is then extended, and a splint is applied to preserve it in the straight position.” (In the paragraph which follows, he describes the successful conclusion to an operation on a Lincolnshire farmer by his nephew, Bransby Cooper: this paragraph ends with the comment “... he perfectly recovered the use of his foot” which is confusing unless interpreted as a return to the main topic of this section of the chapter, viz. the surgical correction of hammer toe.) Cooper’s discussion of the treatment of Dupuytren’s disease was to be misquoted again and again in the French literature, first by Dupuytren and then by those who followed him, as an absolute statement that the disease was incurable. In fact, Cooper had realised, presumably as a result of long clinical experience (this description of the management of the condition was written 14 years after the lecture recorded by John Windsor), that only disease of the palm was amenable to fasciotomy and then only if the bands were narrow. Surgery of the hand was undertaken at that time only when injury and infection demanded attention. Without anaesthesia, and with death from sepsis a not infrequent sequel to surgery, there can have been few candidates for elective hand surgery and few surgeons willing to attempt more than the smallest of procedures. This may explain the seeming lack of interest of the London surgeons in this condition, and the limitations which they set on the use of surgery for its cure. It is of interest to speculate on why Dupuytren was THE JOURNAL OF HAND SURGERY 250 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 REVIEW ARTICLE: THE EARLY HISTORY OF CONTRACTUREOF THE PALMAR FASCIA Fig. 3 Notes of Thomas Smart, student, from a lecture by Henry Cline, 1787. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Library of St. Thomas’ Hospital Medical School, London). unaware of this work by the surgeons of the United Hospitals, when most of the surgeons in England had probably heard, directly or indirectly, of Cline’s treatment of the condition, and when Astley Cooper and Dupuytren communicated with and visited each other on several occasions during the period which preceded the latter’s famous lecture of 5 December 183 1, (Fig. 4). In this lecture, he admitted to having seen 30 or 40 cases himself over the previous 20 years of practice. That he did not treat these surgically suggests that, as he stated, he was unaware of the true cause of the contracture before 1831. In 1822, he was the senior editor of the second edition of Sabatier’s Mddicine Opkratoire. Though he used this publication to introduce his classification and management of burns, and discussed at length the treatment of the burned hand, he made no mention of contracture of the palmar fascia. He would have been conversant with the Trait4 des Maladies Chirurgicales, the massive work in eleven volumes written by his first patron and teacher, Baron Alexis Boyer, personal surgeon to Napoleon Bonaparte. This work remained the main surgical text in France until supplanted by the teaching of Dupuytren himself, in the Lepns Orales..., in 1832. In the eleventh and final volume, written in 1826, Boyer summarised French surgical opinion of that time: he attributed this VOL. 13-B No. 3 AUGUST contraction of the fingers to a drying, harclening and stiffening of the flexor tendons and the overlying skin, a condition which had been called “Crispatura Tendinum” by earlier writers. (Boyer has been frequently misquoted as the source of this descriptive Latin phrase: in keeping with most of his Trait&,which was an aggregation of current surgical opinions rather than a treatise of original ideas, the phrase was not Boyer’s nor did he lay claim to it.) That Dupuytren expressed no contrary view to the theory of Crispatura Tendinum suggests that, in 1826, he concurred with the popular view of the condition in Paris. Whereas Dupuytren worked in an environment in which the newly-introduced medium of medical journalism had flourished to the extent that Paris had at least three weekly and two monthly medical journals, Cline belonged not only to a different generation but also to a less medically cosmopolitan city: even by 1830, London had a much smaller medical press. Chne’s active surgical life largely pre-dates medical journalism. He wrote virtually nothing: his medium was the lecture and it is only through the notes of his students and the writings of his younger contemporaries, particularly Cooper, that his work is known It is likely that the only knowledge Dupuytren had of Cline was that gleaned in conversation with Cooper, In an era of great surgical i988 251 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 D. ELLIOT “ Sir Astley’s Episode for a Guy’s Pageant. fame was European, so that distinguished foreign surgeons never failed to visit him at the . . . . When he took leave he s&l tted Hosp ital. We read of Dupuytren going round the wards with him. the Mrorthy baronet on each cheek. The manner in which Sir Astley submitted to the ceremony affordedI no small amusement to the pupils standing round.“--Wxrxs AND BETTAKY’S HISTORY. Fig. 4 DWUJrtren’s visit to (Rel:produced by Guy’s Hospital, London, in 1826. kind permission of the Editor of the Guy’s Hospital Gazette). THE JOURNAL OF HAND SURGERY 252 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010 REVIEW ARTICLE: THE EARLY HISTORY OF CONTRACTURE discovery with these two men pioneering the treatment of aneurysms, Dupuytren the first to resect the lower jaw and Cooper performing a hind-quarter amputation (without anaesthesia) in 35 minutes - the two men must have had so much to discuss that Cooper may have forgotten even to mention this condition of the hand about which he was consulted little, on which he operated even less and for which the treatment was considered to be “easy and efficacious.” This paper is based on the first part of the Essay which was awarded the Pulvertaft prize of the British Society for Surgery of The Hand in 1987. The second and third parts will appear in our next two issues. References ADAMS, W. Observations on contractions of the fingers (Dupuytren’s Contraction). London, J. & A. Churchill, 1879: 11, BOYER, A. Trait4 des Maladies Chirurgicales, Volume Il. Paris, Migneret, 1826: 55-56. BROCK, R. C. The life and Work of Astley Cooper. Edinburgh, E. & S. Livingstone, 1952. BRUNER, J. M. (1970). The dynamics of Dupuytren’s disease. The Hand, 2: 2: 172.177. CLINE, H. (Senior) Notes on Pathology and Surgery, Manuscript 28, London, St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School Library, 1777: 185. CLINE, H. (Senior) Notes of Thomas Smart (student) from a lecture by Henry Cline senior, Manuscript 29, St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School Library, 1787. CLINE, H. (Senior) - bibliographical sources. See South, J. F., 1884. Parsons, F. G. 1934. Manuscript Collections - Guy’s Hospital, London. St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School, London. Royal Society of Medicine, London. OF THE PALMAR FASCIA CLINE, H. (Junior) Notes of John Windsor (student) from a lecture by Henry Cline junior, Manuscript Collection, Manchester, John Rylands University Library, 1808: 486-489. COOPER, A. P. On Dislocations of the Fingers and Toes - Dislocation from Contraction of the Tendon. In: A Treat5e on Dislocations and Fractures of the Joints. London, Longman & Co., 1822: 524-525. (Translated by Chassaignac, E. et Richeiot, G. as: Oeuvres Chirurgicales compl&es de Sir Astley Cooper. Paris, Btchet, 1837: 122-123.) COOPER, A. P. - bibliographical sources. See Editorial, Lancet, 1826, 10: 861-862. Wilks, S. and Bettany, Cl. T., 1892. Power, D. A., 1933. Parsons, F. G., 1934 and 1936. Brock, R. C., 1952. Manuscript collections - Guy’s Hospital, London. Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh” Royal College of Surgeons of England. Royal Society of Medicine, London. St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School, London. DUPUYTREN, G. Legon Orales de Ciinique Chirurgicalefaitessd i’H@elDieu de Paris M. le Baron Dupuytren, Chirurgien en chef. 1st Edition, Vohune 1, Paris, Germer Bailhere, 1832. (Translated by Doane, A. S. as Clinica/ Lectures on Surgery delivered at Hotel Dieu New York, Collins & Hannay, 1834.) GRACE, D. L., McGROUTHER, D.A. and PHILLIPS, H. (1984). Traumatic correction of Dupuytren’s contractme. The Hand, 9-B: 1: 59-60. HUNTER, J. The Works of John Hunter, F. R. S. edited by Palmer J. F., Volume 1, London, Longman & Co., 1835: 53. HUNTER, J. - bibliographical sources. See Manuscript coilections. Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Royal College of Surgeons of England. PARSONS, F. G. The History of St. Thomas Hospital3 Volumes 2 and 3. London, Methuen &Co. Ltd., 1934 and 1936. PLATER, F. Observationurn in Hornin& Affectibus, Volume 3. Basel, Konig & Brandmyller, 1614: 140. POWER, D’A. (1939). Some Bygone Operations in Surgery. XI The removal of a sebaceous cyst from King George IV. British Journal of Surgery, 20: 1. REDFERN, A. B. (1986). Correspondence Newsletter of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 1986-71. SABATIER, R. B. De la Midicine Opt+aioire, 2nd Edition, Volume I. Paris, Bechet, 1822: 475-482 & 507-512. SOUTH, J. F. Memorials of John Flint Sourh. London, Murray, 1884. TUBIANA, R. and HUESTON, J. ‘I. La maladie de Dupuytren, 3rd Edition, Monographies du Groupe d’Etudes de lz Main, Paris, Expansion Scientifique Francaise, 1987. WILKS, S. and BETTANY, G. T. A Biographical Hislory of Guy’s Hospital, London, Ward & Co., 1892. VOL. 13-B No. 3 AUGUST 1988 253 Downloaded from jhs.sagepub.com by guest on December 22, 2010