PDF - Political Comedy in Aristophanes

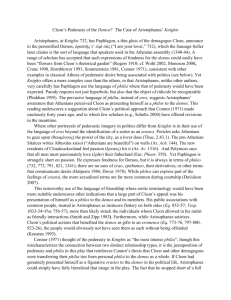

advertisement