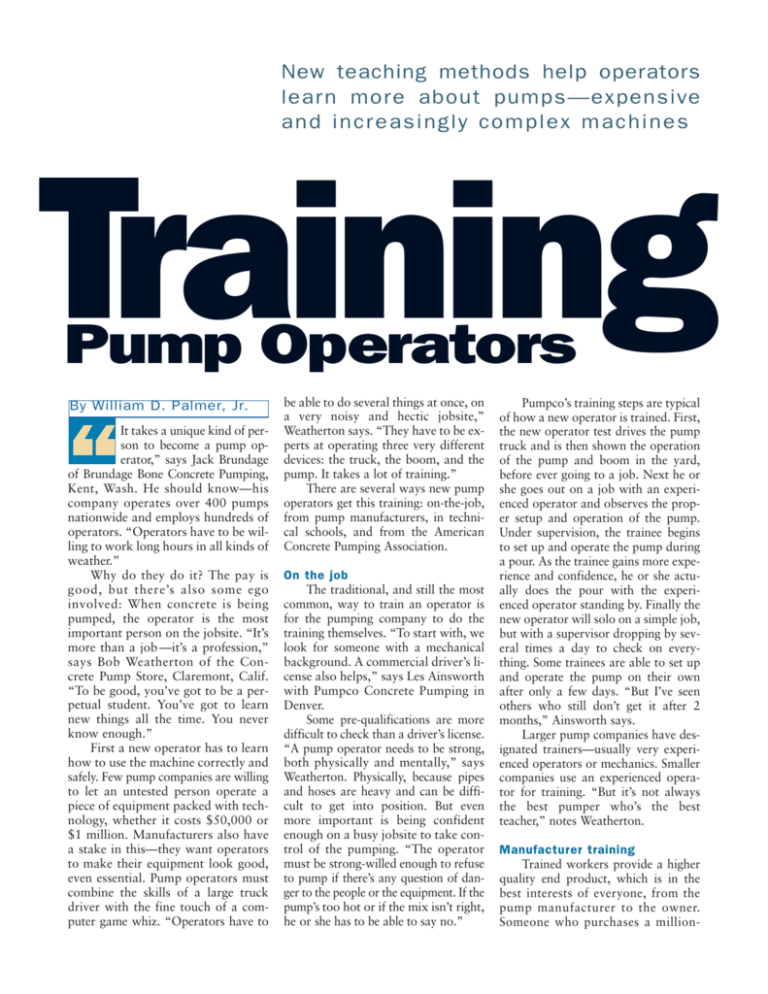

New teaching methods help operators

lear n more about pumps—expensive

and incr easingly complex machines

Training

Pump Operators

By William D. Palmer, Jr.

“

It takes a unique kind of person to become a pump operator,” says Jack Brundage

of Brundage Bone Concrete Pumping,

Kent, Wash. He should know—his

company operates over 400 pumps

nationwide and employs hundreds of

operators. “Operators have to be willing to work long hours in all kinds of

weather.”

Why do they do it? The pay is

good, but there’s also some ego

involved: When concrete is being

pumped, the operator is the most

important person on the jobsite. “It’s

more than a job —it’s a profession,”

says Bob Weatherton of the Concrete Pump Store, Claremont, Calif.

“To be good, you’ve got to be a perpetual student. You’ve got to learn

new things all the time. You never

know enough.”

First a new operator has to learn

how to use the machine correctly and

safely. Few pump companies are willing

to let an untested person operate a

piece of equipment packed with technology, whether it costs $50,000 or

$1 million. Manufacturers also have

a stake in this—they want operators

to make their equipment look good,

even essential. Pump operators must

combine the skills of a large truck

driver with the fine touch of a computer game whiz. “Operators have to

be able to do several things at once, on

a very noisy and hectic jobsite,”

Weatherton says. “They have to be experts at operating three very different

devices: the truck, the boom, and the

pump. It takes a lot of training.”

There are several ways new pump

operators get this training: on-the-job,

from pump manufacturers, in technical schools, and from the American

Concrete Pumping Association.

On the job

The traditional, and still the most

common, way to train an operator is

for the pumping company to do the

training themselves. “To start with, we

look for someone with a mechanical

background. A commercial driver’s license also helps,” says Les Ainsworth

with Pumpco Concrete Pumping in

Denver.

Some pre-qualifications are more

difficult to check than a driver’s license.

“A pump operator needs to be strong,

both physically and mentally,” says

Weatherton. Physically, because pipes

and hoses are heavy and can be difficult to get into position. But even

more important is being confident

enough on a busy jobsite to take control of the pumping. “The operator

must be strong-willed enough to refuse

to pump if there’s any question of danger to the people or the equipment. If the

pump’s too hot or if the mix isn’t right,

he or she has to be able to say no.”

Pumpco’s training steps are typical

of how a new operator is trained. First,

the new operator test drives the pump

truck and is then shown the operation

of the pump and boom in the yard,

before ever going to a job. Next he or

she goes out on a job with an experienced operator and observes the proper setup and operation of the pump.

Under supervision, the trainee begins

to set up and operate the pump during

a pour. As the trainee gains more experience and confidence, he or she actually does the pour with the experienced operator standing by. Finally the

new operator will solo on a simple job,

but with a supervisor dropping by several times a day to check on everything. Some trainees are able to set up

and operate the pump on their own

after only a few days. “But I’ve seen

others who still don’t get it after 2

months,” Ainsworth says.

Larger pump companies have designated trainers—usually very experienced operators or mechanics. Smaller

companies use an experienced operator for training. “But it’s not always

the best pumper who’s the best

teacher,” notes Weatherton.

Manufacturer training

Trained workers provide a higher

quality end product, which is in the

best interests of everyone, from the

pump manufacturer to the owner.

Someone who purchases a million-

dollar piece of equipment rightfully

expects training to be included, and

most pump manufacturers provide

some initial operating training as well

as service training. Often the local distributor conducts this training.

Dave Hirt, with Reich Construction Equipment, says that the sale of

a pump includes a training expert to

work with new owners until they are

comfortable with the specific characteristics of the new pump. “Most of

the time, they are already familiar with

pumping. We work with them for 2 or

3 days, going through all the controls,

basic maintenance, troubleshooting,

the parts manual, and the major dos

and don’ts. Then we make sure they

know who to call if problems arise.”

Of all the pump manufacturers,

Schwing conducts the most ambitious

training program. It conducts service

seminars on three levels: operator

(Level 1), mechanic (Level 2), and

advanced mechanic (Level 3). Courses

at each level are held two or three

times each year at Schwing’s training

center in St. Paul, Minn. The registration fee is around $900. “All of the

training materials and programs are

sold to the customer at cost,” says

Schwing’s training director Phil Seere.

To supplement the seminars, or as

stand-alone self-paced study, Schwing

has an extensive collection of CDROMs on every aspect of servicing

booms and pumps.

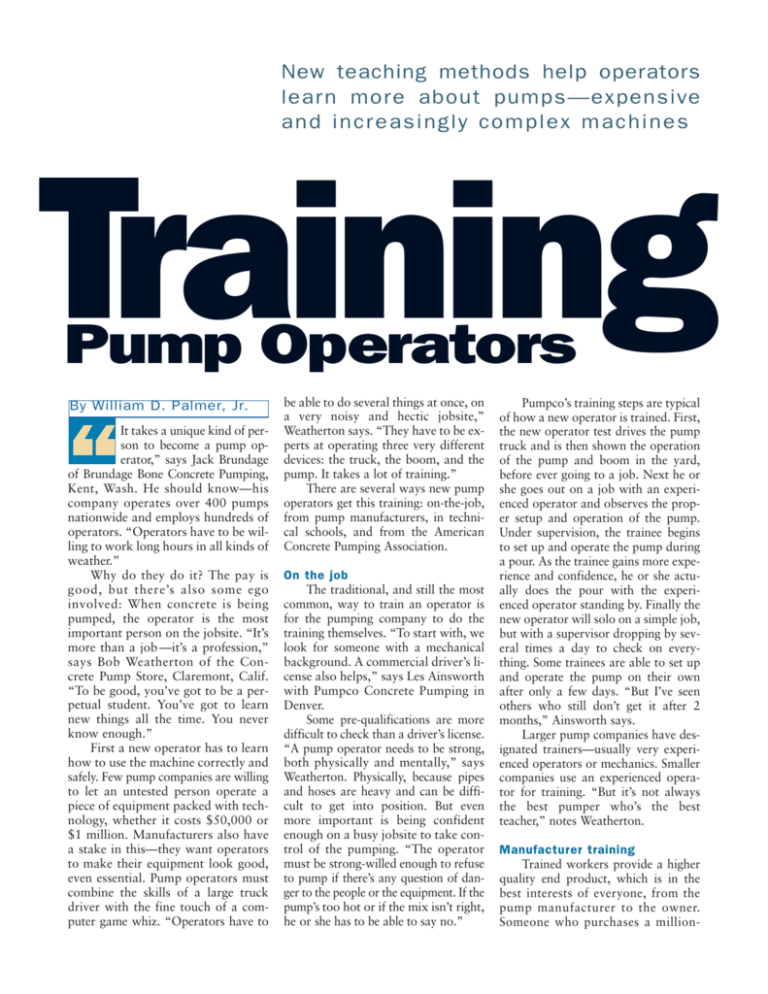

Schwing’s newest training innovation is its Virtual Boom—a very realistic concrete pumping computer game.

At this year’s World of Concrete, Seere

gave me a quick lesson and then let me

take the controls. Using a real remote

pump and boom controller, this computerized pump is extraordinarily lifelike. I selected the 52-meter boom, then

started the truck engine. The engine

rumble grew softer as I moved away

from the truck to find a position that

would give the best perspective to

watch and control the pumping. I started with a basement wall pour, and

found that I’d positioned the truck

poorly—too close to power lines. Once

“It hurt to do it, but we took our best operator off

the pumps and made him a full-time trainer,” says

Rod Pugliese with Brundage-Bone in Denver. “He

even observes the veterans from time to time to

make sure they aren’t getting sloppy.”

the pump truck was moved to a better

location, I unfolded the boom one section at a time and awkwardly slewed

and extended the boom to position the

hose to begin pumping. Finally, a voice

yelled out, “OK, you’re ready to pump.

Go ahead!” I turned on the pump and

watched the wall fill with concrete.

Controlling the boom with the

two joysticks takes some practice. One

stick controls two boom sections, and

a third boom section and the slewing

are controlled by the other. As I finished pumping a second floor deck

slab, I slammed the boom into the

deck, earning a reprimand from the

hoseman: “Oh man, you need to go

work for the competition!”

Another Schwing training program is a virtual pumping “room” for

beginners, where the operator learns

the basic controls without the simulated pressure of a real jobsite. In this

part of the program, you learn to

pump into boxes from various positions and elevations and to best position yourself to see where the end of

the boom is in relation to your target.

Depth perception on the screen can be

as deceiving as it is on a real jobsite.

Other software packages teach the

operator how to determine if all systems and controls are working properly, and how to adjust the sensitivity of

the controls to personal preferences.

For pump mechanics, Schwing has

extensive service software to help troubleshoot a problem. The diagnostics system is so detailed that, for example, it

shows exactly where to put the leads of a

multimeter and what the meter should

read. Every circuit and every hydraulic

line is traced and its function is described.

Putzmeister also conducts an

extensive schedule of classes at its

headquarters in Racine, Wis., that are

primarily oriented toward maintaining

and servicing the equipment. Attendees are expected to arrive with a

basic working knowledge of concrete

pumps. Courses combining classroom

with hands-on training cover large line

pumps, trailer pumps, and boom inspection. These courses are free to

Putzmeister customers.

Technical colleges

Despite the best efforts of the

pumping companies to support technical college programs for operators,

Schwing’s Virtual

Boom allows operators-in-training to

become familiar

with the controls

before moving to a

real boom.

there is no current functioning program. That will change in May with

the initiation of a program at the Autry

Technology Center in Enid, Okla. (see

July 2000, p. 33). With support from

Pumpstar Concrete Pumps and several

local ready-mix companies, Autry

plans to start five students on a 3- to 4month-long program that will be computer-based but led by an instructor.

Instructor Casey Blaine says that the

program “pulls concepts from other

programs and tailors them to the

pumping industry’s needs. Our hope is

that the industry will recognize the program and provide feedback so that we

can give students the training they need

to be productive on the job.” This program will combine classroom instruction with co-op work at Pumpstar.

Schwing has, for the past 4 years,

supported a course for pump opera-

tors at Central Lakes College in

Staples, Minn. Similar to the program

being planned in Oklahoma, this program has unfortunately been suspended due to a lack of students.

American Concrete Pumping

Association

Members of the ACPA include the

top people at many of the largest concrete pumping companies in the

United States as well as the owners of

many small companies. In its continuing efforts to raise the level of professionalism across the industry, ACPA

has developed the following programs

and materials that emphasize that

pump safety and efficiency are completely intertwined:

■ Recommended training procedures for pump operators that includes a long checklist of things every

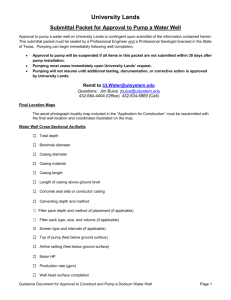

What does an operator need to know?

■ Commercial driving (leading to a CDL)

■ Diesel engines

■ Basic hydraulics

■ Basic electrical systems

■ Basic electronics

■ Schematic reading (hydraulic and electrical)

■ Basics of concrete, including mix design

■ Common pump and boom parts and how they function

■ General construction site safety

■ Safe pump and boom operating procedures (especially setup

and cleanout)

■ Preventative maintenance

■ Emergency jobsite troubleshooting and repair

This list is a compilation of the courses offered at community colleges and by the manufacturers.

operator should know.

■ The association’s lengthy list of

safety videotapes complements an operator’s training. “A lot of companies

will make the operator watch the

videos and sign off,” Weatherton says.

■ A series of safety posters reminds operators of safe practices such

as relieving the pressure before opening

a line, fully extending the outriggers,

and not standing on the hopper.

■ ACPA’s pump operator certification program “identifies experienced

operators and ensures recognition of

a concrete pump operator’s safety

awareness.” ACPA certification indicates that the operator knows the

book, although it does not indicate

that the worker is qualified to pump.

Two levels of certification in eight categories include safety, trailer pumps,

short booms, and large booms. A

“safety card holder” is someone who

has passed the examination but does

not yet have the required experience.

Once experienced, the operator can

upgrade to full certification. Certification can be an important part of

training. “When we hire an operator,”

says Ainsworth, “it’s on a 90-day probation, and we expect operators to get

ACPA certified within that 90 days.

They won’t get a raise until they do.”

■ ACPA has developed a complete

safety training series (see box) that a

pumping company can conduct in two

ways: the company can administer the

program itself, or an operator can complete the course through Classroom

America. With Classroom America, the

pumper gets a workbook and studies the

materials at his or her own pace. When

finished with each of the 12 chapters,

the student calls an 800 phone number

to take an automated over-the-phone

quiz. The company then gets a report on

how its employees performed on the

quiz, emphasizing areas where an

operator is weak and might need some

extra help.

Training of pump operators

improves the quality of concrete and

makes the jobsite safer. But training

is also defensive—ACPA estimates

that the average accident costs

$250,000 and possibly much more if

the courts get involved. When there’s

a problem on a job, or someone gets

hurt, and the lawyers drag everyone

into court, a documented training

program gives pumping companies

and manufacturers a much stronger

hand. ■

For further information

American Concrete Pumping Association,

614-431-5618, www.concretepumpers.com,

or circle 1 on the reader service card

Autry Technology Center, 580-242-2750,

or www.autrytech.com, or circle 2 on the

reader service card

Pumpstar, 580-548-2723,

www.pumpstar.com, or circle 3 on the

reader service card

Putzmeister America, 262-886-3200,

www.putzmeister.com, or circle 4 on the

reader service card

Reich Construction Equipment, 803-9801120, www.reichpumps.com, or circle 5

on the reader service card

Schwing America Inc., 651-429-0999,

www.schwing.com or circle 6 on the

reader service card

ACPA’s Safety Training Series

■ Job setup

■ Before driving to the job

■ Pumping the job

■ Co-worker safety

■ Moving the pump during the pour

■ High-tension wires

■ The basics when working with a pipeline

■ Cleaning a separately laid pipeline

■ Cleaning the pump

■ Pinch points and cut-off points

■ Maintenance issues

Publication #C01D024

Copyright © 2001 Hanley-Wood, LLC

All rights reserved