PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND DIFFERENCES Traits

advertisement

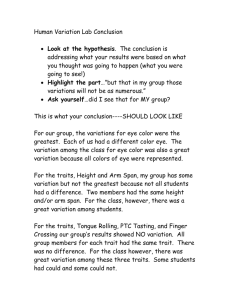

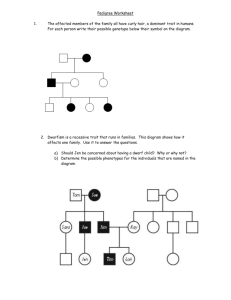

PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND DIFFERENCES Traits, Consistency, and Self-Schemata: What Do Our Methods Measure? Pamela A. Burke, Robert E. Kraut, and Robert H. Dworkin Cornell University Psychologists have responded to the inadequacies that Mischel (1968) noted in the trait approach to personality by exploring two other facets of personality, cross-situational consistency and self-schemata. These newer approaches have yet to be clearly distinguished conceptually or empirically from the traditional model that they were designed to supplement or replace. Our research tries to do this. In it, two samples of respondents (N = 362) rated the extent to which, of 10 traits applied to them (overall level), rated their consistency on these traits (crosssituational consistency), and rated the importance of these traits to their view of themselves (self-schema). Correlational analyses show that the measures of consistency and self-schema lack discriminant validity from the measures of overall level. Specifically, their correlations with level were as high as their internal consistencies. We argue that the measurement models for cross-situational consistency and for self-schemata do not adequately reflect their theoretical counterparts. This failure undercuts the interpretations of recent research by Markus (1977), Markus, Crane, Bernstein, and Siladi (1982), and S. Bern (1981). To a great extent the results of psychologists' attempt to understand personality has been a list of personality traits and research on their causes, correlates, and consequences. But Mischel (1968) and others (Peterson, 1968; Vernon, 1964) severely questioned the value of this enterprise. One of the responses to Mischel's criticism of the trait approach to personality has been the introduction of two alternative ways of thinking about personality—the cross-situational consistency approach and the self-schema approach. Our intention in this article is to examine the conceptual distinctions among the facets of personality posited by these three approaches and the methods for measuring them. We Portions of this research were supported by National Science Foundauon Grant BNS-7907963 to the second author. An earlier version of this research was presented at the Eastern Psychological Association Meeting, New York, 1981. Robert Kraut is now at Bell Communications Research, Murray Hill, New Jersey. Robert Dworkin is now at the Departments of Anestheaology and Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons. Columbia University, New York, New York. Requests for reprints should be sent to Pamela Burke, who is now at the Department of Psychology, Building 420, Jordan Hall, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305. especially concentrate on the self-schema approach. Overall Level The traditional trait approach has generally regarded a trait (the extent to which an individual is high, moderate, or low on a personality dimension) as a latent tendency to act consistently with one's level on that dimension (Magnusson & Endler, 1977). We refer to this measurement as overall level. As Magnusson and Endler note, many of the arguments about the usefulness of this way of conceptualizing personality come from empirical refutations of the trait measurement model and not from theoretical disagreements. The trait measurement model makes two assumptions that lead to predictions unsubstantiated by empirical research. The model assumes that each individual possesses a true score on each personality trait and that an accurate measurement of this score will be monotonically related to each behavioral measure of that trait. These assumptions imply that stable rank orders of individuals exist across situations in the expression of trait-related behavior. Journal of Personality and Soaal Psychology. 1984. Vol 47, No 3, 568-579 Copyright 1984 by the American Psychological Association. Inc 568 TRAITS, CONSISTENCY, AND SELF-SCHEMATA 569 A person's overall level on a trait is generally measured through the use of self-reports. Single item questions that ask directly for the person's extremity on the trait and personality inventories, (i.e., multiple item tests that produce a composite score on a trait, e.g., California Personality Inventory, [CPI] Gough, 1969), are typically used. Theoretical and empirical justification for the use of single item global measures of traits (Kenrick & Braver, 1982; Peterson, 1965) continues alongside research demonstrating the efficacy of composite scales in behavioral assessment (Epstein, 1979; Moskowitz, 1982; Rushton, Jackson, & Paunonen, 1981). model. Schema theorists think about traits in terms of cognitive generalizations about the self. Like consistency theorists, they dismiss the assumption of a one-to-one correspondence between a person's level on a trait and his or her trait relevant behavior. People's self-schemata are not dependent on their overall level on a trait but rather on the personal significance or salience of the trait dimension to them. That is to say, their cognitive organizations determine which dimensions are salient and important to them. According to this view, people with different schemata interpret and respond to the same stimuli in different ways. Cross-Situational Consistency Systematic effects in social behavior depend less on people having some amount of a particular substantive attribute, such as independence or dependence, and more on the readiness or ability to categorize behavior along certain dimensions. (Markus, 1977, p. 77) Cross-situational consistency theorists have responded to the apparent unpredictability of behavior demonstrated by the traditional trait measurement model by specifying the conditions under which traits predict behavior. They assert that behavioral consistency is a function of both the meaning of the trait and the meaningfulness of that trait to the individual. This approach maintains that stable cross-situational consistency in behavior is characteristic of people for some, but not all, traits. Thus, the accurate prediction of behavior depends on knowledge of the traits on which an individual is consistent and knowledge of the behaviors he or she sees as relevant to those traits. As a result, according to these theorists, traditional trait research that measures only a person's level on a trait, has underreported the predictability of behavior. Consistency researchers have attempted to demonstrate that measuring self-reported consistency improves the prediction of behavior. For example, D. Bern and Allen (1974) have shown that, at least for the trait of friendliness, people can report how consistent they are across situations. They argue that one can predict friendly behaviors from measures of overall level better for consistent people than for inconsistent ones (cf. Mischel & Peake, 1982). The Measurement Problem We have sketched the conceptual relations between the traditional level model of traits and two alternative models, a cross-situational consistency model and a self-schema model. They both hold promise of remedying the inability of the traditional trait model to strongly predict behavior. Before they are accepted, however, their empirical relations to the traditional measurement model of traits must be examined. If they show only a small relation to overall level, then a combination of the new models with the traditional model might predict behavior better than either alone. On the other hand, despite their conceptual independence, the new measures of traits may be highly related to the traditional level measure. In this case little is gained by hiding the use of traditional methods under new labels. Previous research leaves the relation among the three models of personality in doubt. The standard method of measuring cross-situational consistency in personality precludes assessing its natural relation with overall level. For example, D. Bern and Allen (1974) and Zanna, Olson, & Fazio (1980) statistically controlled level when measuring consistency. Self-Schema Stones and Burt (1978) and Rushton et al. A theory of self-schema is another response (1981), however, have found that the more to Mischel's critique of the traditional trait. extremely people rate their level on a personal 570 P. BURKE, R. KRAUT, AND R. DWORKIN trait, the more they also rate themselves as Measures consistent on that trait For example, people The questions were self-report items designed to assess who rate themselves as moderate on a trait participants' trait level, trait consistency, and self-schema also rate themselves as highly variable across for the three traits of friendliness, intelligence, and articsituations. Other measures of cross-situational ulateness. We used friendliness and intelligence as target consistency (Kenrick & Stringneld, 1980) have traits because of their repeated assessment in the personality literature and because of their independence. We been criticized for ignoring trait extremity used articulateness because it is a more specific trait with entirely (Rushton et al., 1981). clear behavioral manifestations. Questions about other Self-schema theorists have confounded traits were added as filler items so that the target traits would not be recognized as the focus of inquiry. The measures of schema and measures of level specific questions used are shown in Table 1. The reliand, therefore, have obscured the relation abilities and validities of several of these measures are between peoples' schemata about a trait and unknown. They were chosen because they are the meatheir level on that trait. Thus for researchers sures commonly used by researchers in the field or are such as Markus (Markus, 1977; Markus et directly derivative of the proposed theories. Level. The four measures were traditional self-report al., 1982) and S. Bern (1981; 1982), a person liken scales, on which participants reported the extent who is schematic on a trait is one who has to which a trait described them, either in general, coman extreme level on that dimension and who pared to their peers, or in particular social circumstances, considers the dimension important. The re- (e.g., In general, how [friendly] are you?) Self-schema. Schema theorists like Markus (1977) lation between level and importance is unand S. Bern (1981) define self-schema as the importance clear. of and readiness to use a trait dimension in thinking Finally, the relation between consistency about one's self and the world. However, they measure it and self-schema is also of interest. For ex- by combining measures of importance with measures of ample, although Markus (1977) posits a pos- level. To determine the relation of the importance of a for a person to that person's level on the itive relation between the two, no data yet dimension dimension, we isolated these components. We measured exist to support this claim. self-schema by asking questions about the importance Overview The empirical goal of the present article is to test the discriminant validity of methods to measure peoples1 overall level on a trait, their cross-situational consistency on that trait, and their self-schema on that trait We used several self-report measures of trait level, cross-situational consistency, and self-schema that were obtained from previous research or designed for the present studies. Participants described themselves on these measures for each of several traits. The correlations between all measures were computed to assess the naturally occuring relations among level, consistency, and schema and to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity of these facets of personality. Study 1 Method Participants and Procedures One hundred and ninety male and female college undergraduates at Cornell University were paid $.50 to complete a brief questionnaire. people assigned to a trait (e.g.. How important is friendliness . . . to the image you have of yourself, regardless of whether or not the trait describes you? [from Markus, 1977]. We also asked about their readiness to use the trait in thinking about themselves and others, (e.g., When attending a lecture, how frequently do you judge how friendly the speaker is?) Cross-sittuuional consistency The questions here were modeled after those used by D. Bern and Allen (1974). They included both participants' self-reports on consistency (e.g., How much do you vary from one situation to another in how friendly you are?) and the standard deviation of their self-reported level in different social circumstances (e.g., friendliness with parents, friends, or siblings). Results The central datum of this article is a comparison of the internal consistency of the various level, schema, and consistency measures with their discriminant validity. We computed Pearson correlations between all measures of level, schema, and consistency separately for the traits of intelligence, friendliness, and articulateness. The signs and magnitudes of the correlations were highly similar across the three traits. We have presented the comparison twice, once averaging over measures and once averaging over traits. TRAITS, CONSISTENCY, AND SELF-SCHEMATA 571 Table 2 shows the z-transformed correla- item correlation matrices of the three traits tions for the three traits of friendliness, intel- to test the independence of the three facets ligence, and articulateness, averaged over of personality. We performed a principal axis measures. Table 1 presents the mean z-trans- factor analysis with oblique rotation separately formed correlations for the different measures for each trait The hypothesis of independence of level, consistency, and schema averaged would predict a three factor solution with over traits. measures of level, self-schema, and consisAs Tables 1 and 2 show, the internal con- tency loading primarily on three distinct facsistency of the traditional trait level measures tors. Instead, at least four factors were ob(mean interitem correlations = .34) was at tained for each trait (eigenvalue > 1.0) and least as high as that of the schema measures more important, measures of level, self(mean interitem correlations = .20) or the schema, and consistency do not cohere on cross-situational consistency measures (mean separate factors. The factors, though highly consistent across traits, show a complex patinteritem correlations = .23).' Tables 1 and 2 also show the cross-corre- tern of relations among the measures, the lations between the various models of person- specific nature of which could not have been ality. The discriminant validity of both the predicted in advance. schema and the cross-situational consistency Table 3 presents the results from the analmodels of personality was weak. Specifically, ysis of the measures of friendliness. Four the mean correlation between measures of factors account for 63% of the variance in schema and measures of level (mean r = .23) these measures. The major factor (Factor 1) was as high as the internal consistency of the for friendliness and for the other two traits schema measures (mean r = .20). This means consists of two level measures and three selfthat items designed to measure schema cor- schema measures (In Table 3, items 1, 2, 5, relate as highly with items designed to mea- 6, and 7). The schema measures involving sure level as they do with each other. The the judgments of others also load on this two consistency measures show no linear factor for two traits (items 10, 11, and 12). relation to either the level measures (mean For all traits, Factor 2 is composed of level r = .14) or to the schema measures (mean judgments on a trait when the judge is with r = .04). significant others and the self-schema measure Unlike Stones and Burt's (1978) data, we of confidence (items 3 and 8). In addition, found no curvilinear relation between consis- across the three analyses, other level and selftency and trait level. We computed polariza- schema measures load inconsistently on this tion scores for each participant on each trait, factor. Factor 3 for all three traits is composed by taking the absolute value of the difference of the consistency measures. It also includes between each participant's score on a measure a mixed pattern of both level and self-schema and the group mean on that measure. The measures. Factor 4 consists of the level meacorrelations of the consistency measures with sure comparing self to peers, and an inconthe polarization scores are low (mean sistent pattern of other level, self-schema, and consistency measures. T = .06). The argument against the internal consisStudy 2 tency and discriminant validity of the selfschema and the cross-situational consistency Method measures is based on the patterns of correlations we have presented and not on their Participants and Procedures One hundred and seventy-two undergraduate women absolute magnitudes. Given the way that we aggregated correlations over measures and from Cornell University were recruited through newspaper traits and the nonindependence of the correlations, we could not directly test the signifi1 The reliability for the cross-situational consistency cance of the difference between mean corre- measure is very similar to the interitem correlations that lations. Therefore, to examine these patterns D. Bern and Allen (1974) found for similar more explicitly, we factor analyzed the inter- (r •= .22). Table 1 Correlations Among All Measures of Level, Self-Schemata. and Consistency, Averaged Across Three Trail Dimensions: Study 1 Self-schemata Level Measures Level 1. In general, how are you? 2. Trait describes me/does not describe me. 3. How are you with your parents, friends, etc.? (Mean of 10 judgments) 4. Compared to your peers, how are you? Self-schemata 5. How important is trait in describing yourself honestly to someone? 6. Importance of trait to your image of yourself? 7. Importance of trait in understanding your personality and behavior? 8. Confidence ratings of how you are with 10 specific others. 9. How easy is it for you to judge yourself on the trait ? 10. How easy is it to judge a friend on trait ? 11. Importance of trait in understanding a friend's personality and behavior? t Consistency 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 .73 .44 .14 .38 .40 .46 .19 .16 .20 .22 .23 .24 .06 .47 .12 .37 48 .37 .19 .19 .24 .25 .29 .13 .19 .14 .28 .27 .25 .48 .19 .18 .11 .20 .17 .23 .07 .16 .09 .10 .09 .15 .12 .12 .03 -.01 .39 .40 .16 .15 .24 .37 .25 .13 .01 51 .11 .10 .18 .31 .28 .09 .12 1 .13 .08 .14 .31 .29 .11 .07 .09 .09 .06 .08 .12 -.09 .06 .03 .14 .06 -.01 .26 .14 .01 .04 .21 .05 .05 TRAITS, CONSISTENCY, AND SELF-SCHEMATA o 573 advertisements and posters. They completed a set of personality questionnaires and were paid $2.50. 3 'in a 1 Measures 8 The questionnaires we used in this study were originally developed to measure the three facets of personality for the trait of friendliness, as part of a study on memory for events. In addition, we included a less complete set of measures of the three facets for the traits of conscientiousness, independence, honesty, sensitivity, anxiety, activity level, and assertiveness Trait level. At least one of three different measures of level were obtained for each trait dimension. These included global self-reports for all eight trait dimensions (e.g., In general, how friendly are you?), self-reports about five traits in a number of different situations (The CrossSituational Behavioral Survey (CSBS), D. Bern & Allen, 1974), and a reliable personality inventory (CPI Sociability Scale). Self-schema We adapted two versions of Marfcus's (1977) self-report measures of self-schema to make them conceptually independent of overall level. Each was administered to approximately half the sample. In addition, we adapted the trait-cued autobiography method used by McGuire and Padawer-Singer (1976). Participants were asked to spend IS mm writing a short description of those aspects of their personality that they thought were most important in understanding their own behavior. They were given a list of 24 traits they could choose to use, "because previous participants have found the list helpful in organizing their answers". Two coders coded these short essays as schematic for a trait dimension if the participant used a relevant cue from the cue list, a synonym of it, or an antonym for it. When the coders disagreed on the presence of a cue, the participant was classified as schematic because at least one of the coders had found some mention of the dimension in the autobiography. We obtained the trait-cued autobiography measure of self-schema for seven traits. Cross-situational consistency. We measured crosssituational consistency for each trait through at least one of the two measures used by D. Bern and Allen (1974). These included a direct self-report (e.g., "How much do you vary from one situation to another in how friendly you are?") for all eight traits and the variance in participants' level judgments in a number of social situations (CSBS) for five traits. Results | Pearson product-moment correlations were computed among the measures of level, crosssituational consistency, and self-schema. Table 4 presents means of the correlations for the eight trait dimensions averaging across measures for each trait, and Table 5 presents the means of the correlations averaging across traits for each measure. As in Study 1, measures of overall level show the most convergence, with a mean correlation across measures and traits of .57. The mean internal consistency of the schema measures (r = .21) 574 P. BURKE, R. KRAUT, AND R. DWQRKIN Table 2 Correlations Between Measures of Level, Self-Schemata, and Consistency for the Traits of Friendliness. Intelligence, and Articulateness: Study 1 Schema As a Processing Model Markus and Bern might dismiss this criticism of the schema model. Markus (1977) and S. Bern (1981) denned self-schema in terms of the personal significance of wellConsistency Level Schemata Measure articulated cognitive structures, yet they originally and intentionally measured these strucFriendliness tures in terms of overall level. Markus and .17 .32 .22 Level her colleaques (1982) have dropped personal .09 .18 Schemata significance or importance from their defini.24 Consistency tion of self-schema and yet still consider the Intelligence schema model a supplement to or an alternative to the traditional trait model of perLevel .37 .28 .13 Schemata .22 .06 sonality. They would argue that the schema Consistency .24 model is valuable, even if one cannot measure it independently of a person's level on a trait. Articulateness The schema model provides the cognitive Level .14 .33 .20 mechanism through which trait level has its Schemata .20 .04 effects on beliefs and behavior. Consistency .22 The mechanism is the workings of an autonomous belief system, formed through the differential experience of people who differ and of the cross-situational consistency mea- on their level on a trait. sures (r = .22) were substantially less. Tables 4 and S also show little discriminant With social experience we gain a diversity of self-relevant information that becomes organized into cognitive strucvalidity among the various measures. As in tures. It is by means of these structures that we categorize, Study 1, the mean correlations of level and explain, and evaluate our behavior in various focal schema (r = .30) and of level and cross-situ- domains, (Markus et al., 1982, p. 38). ational consistency (r = .34) were as high as the internal consistency of the self-schema Markus and Bern would argue that the schema concept is the preferred explanation for the and consistency measures. individual differences in the way people process information about themselves. According to this reasoning, the value of the schema Summary and Discussion model rests on the discriminant validity of We have shown that measures of self- underlying cognitive processes and not on the schema and cross-situational consistency lack discriminant validity of a personality meadiscriminant validity. Table 6 summarizes surement. For example, Markus and her students our evidence by averaging the convergent validity correlations and the discriminant va- have found that compared with people who lidity correlations across traits, measures, and are aschematic, people who score as selfstudies. It shows that measures of self-schema schematic on a trait dimension make schemaand cross-situational consistency, although related judgments about themselves more designed to be independent of overall trait quickly and consistently, offer more behavioral level, are not independent. Instead the cor- evidence for their self-judgments, make more relation of each with overall level is as high confident and extreme predictions about fuas its internal consistency. The measurement ture behavior, and change their self-concepmodels for the cross-situational consistency tions less when given counterevidence. approach and the self-schema approach to Both Markus and S. Bern conclude from personality clearly Ml to reflect the conceptual this type of evidence that schematic people models. have an elaborated cognitive structure that TRAITS, CONSISTENCY, AND SELF-SCHEMATA enables them to process relevant information about themselves quickly and efficiently. They both assume that the self-inference strategies that schematics use are qualitatively different from those used by aschematics. Having assumed the existence of schemata, researchers are now trying to distinguish between theoretical types, particularly between self-schemata and gender schemata. (See S. Bern, 1982, for a skillful explication of differences between the two.) However, we believe this investigation is premature. The data on the speed of, conndence in, and richness of self-descriptions are not compelling evidence that some people form their self-descriptions through any sort of schema processing. We have shown that putative schematics and aschematic individuals also differ on trait level. We believe their different levels on traits can account for the 575 data, without postulating qualitatively different processing strategies between schematic and aschematic individuals, For example, consider the data on speed of processing. Both Markus (Markus, 1977; Markus et al., 1982) and S. Bern (1981; citing data from Girvin, 1978 and Markus et al., 1982) argue that the greater speed with which schematic compared with aschematic participants endorse schema-consistent personality descriptions is evidence for the schema model of personality. According to these authors, to answer the question, "Are you independent?" or "Are you nurturant?" schematic people need only look up the correct answer in their preexisting and well-structured self-descriptions or gender-schemata, whereas aschematic people must use different cognitive processes, for example, reviewing and evaluating dimcult-to-abstract behavioral evidence. However, Table 3 Principle Component Analysis With Oblique Rotation for Measures of Friendliness Measures Level 1. In general, how friendly are you? 2. Friendly described me/does not describe me. 3 How friendly are you with your parents, friends, etc.? (Mean of 10 judgments) 4. Compared to your peers, how friendly are you? Self-schemata 5. How important is friendliness in describing yourself honestly to someone? 6. Importance of friendliness to your image of yourself? 7. Importance of friendliness in understanding your personality and behavior? 8. Confidence ratings of how friendly you are with 10 specific others. 9. How easy is it for you to judge yourself on friendliness? 10. How easy is it to judge a friend on the trait friendly? 11. Importance of friendliness in understanding a friend's personality and behavior? 12. When attending a lecture, how frequently do you judge the speaker on friendliness? Consistency 13. How much do you vary from one situation to another in how friendly you are? 14. Standard deviation of how friendly you are with 10 specific others. Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 .73 .81 .41 .44 -.15 -.02 .14 .18 .38 .18 .84 .24 -.09 -.23 .11 -.64 .68 .16 .16 .09 .77 .05 -.21 .29 .74 -.03 -.09 .28 .15 .77 -.25 .35 .03 .40 .16 -.04 .10 .13 -.03 .76 .41 -.23 .31 .64 .43 .16 .64 .19 -.38 -.01 .56 -.40 -.22 -.19 .63 -.08 576 P. BURKE, R. KRAUT, AND R. DWORKJN we can adduce at least two nonschema explanations for why schematic people respond faster than aschematic ones. The threshold account. A threshold account assumes that people apply a trait dimension to themselves when their level on that trait exceeds some subjective threshold and that, on the average, this threshold does not systematically differ among people. Quick responses occur when the individuals' level on the trait is unambiguously distinct from the threshold, that is, when they are extreme on the trait. A closer, more time consuming comparison is required for traits near the subjective threshold, that is, for traits judged moderately self-descriptive. Threshold for- Table 4 Correlations Between Measures of Level. SelfSchemata, and Consistency Presented by TraitStudy 2 Measures Friendliness Level Schemata Consistency Sensitivity Level Schemata Consistency Independence Level Schemata Consistency Honesty Level Schemata Consistency Conscientiousness Level Schemata Consistency Assertiveness Level Schemata Consistency Activity Level Level Schemata Consistency Anxiety Level Schemata Consistency Level Schemata .62 .22 .20 .40 .24 .27 .49 .31 .33 .41 .09 .19 t .26 .19 .53 .19 Consistency • .45 .30 .27 .37 .09 .13 .69 .33 .23 .49 .19 .30 .59 .20 • .20 .00 .20 .33 .15 .42 .16 .42 .16 -.43 -.31 a " Only one measure of this facet was collected for this trait. mutations of the self-referential judgment process have garnered considerable empirical support (Goldberg, 1963; Jackson & Helmes, 1979; Jackson & Paunonen, 1980; Rogers, 1971; Rogers, Kuiper, & Rogers, 1979; Voyce & Jackson, 1977) in the personality measurement literature. Consistent with this formulation, consistency and latency of response to self-ascriptions for a given dimension have been shown to depend on the individual's level on that dimension (Kuncel, 1973). According to the threshold account, aschematics take longer because of the difficulty they have in making discriminations when their level on a trait is close to their subjective threshold for calling it self-descriptive. A similar argument can be made to explain findings (Girvin, 1978; Markus et al., 1982) that sex-typed (i.e., schematic) people were faster at judging sex-congruent traits to be self-descriptive and slower at judging sexincongruent traits to be self-descriptive. Nonsex-typed (i.e., aschematic) people did not show these differences in speed of response. By definition, the schematic people are more extreme in the positive direction on sexcongruent traits judged self-descriptive than on cross-sex-congruent traits judged self-descriptive. On the average, a schematic man would judge himself as more assertive than he is artistic, even though he might apply both terms to himself; any deviations would presumably be the result of measurement error. Aschematic people are by definition equally extreme on sex-congruent and crosssex-congruent traits judged self-descriptive. For example, an aschematic man might judge himself to be highly assertive and artistic, and equally so. As a result, the latency differences between the two types of traits observed for schematic but not for aschematic participants reflects aschematic individuals' choice between equally applicable traits. Evaluation of behavioral evidence. Evaluating behavioral evidence is a second process through which people can decide whether a trait is self-descriptive. This process can also account for the differences between schematic and aschematic individuals' speed of response. Those who show an extreme level on a trait are likely to have had mare and more consistent occasions in which they have acted consistently with the trait In reviewing evidence 577 TRAITS, CONSISTENCY, AND SELF-SCHEMATA TableS Correlations Among all Measures of Level. Self-Schemata, and Consistency Averaged Across Eight Trait Dimensions: Study 2 Level Self-schemata Consistency Trait dimensions 1. California Personality Inventory Sociability item 2. In general, how are you? 3. Cross-Situational Behavior Survey Scale mean 4. Trait-cued autobiography 5 Importance selfreport I 6. Importance selfreport II 7. How much do you vary from one situation to another in how you are? 8. Cross-Situational Behavior Survey Scale variance .53 .64 .03 .33 .08 .37 .32 .59 .20 .52 .36 .36 .18 .14 .29 .35 .43 .44 .22 .20 .03 .01 .21 .11 .15 .03 .22 about their independence, for example, schematic people will be able to retrieve occasions during which they acted independently more quickly. In addition, the evidence they retrieve should be more internally consistent. As a result, they should have an easier and quicker time integrating the evidence and then making their decision. Similar reasoning can account for Markus' behavioral instance data and subjective likelihood data. These data show that people offer the greatest behavioral evidence for those traits that are most self-descriptive and view engaging in behaviors related to these traits in the future as relatively likely. Table 6 Correlations Among Measures of Level. Selfschemata, and Consistency Averaged Across Measures and Traits for Studies 1 and 2 Measures Level Schemata Consistency Level Schemata Consistency .41 .26 .20 .26 .08 .22 Cross-Situational Consistency Evidence Our data on cross-situational consistency measures appear somewhat at odds with the boost in predictive validity reported by researchers who have used them in the past. We would not argue on the basis of our sparse data on these measures that trait level and consistency as commonly measured are completely overlapping constructs. The utility of using consistency and schema measures as moderator variables after trait level has been statistically controlled remains an empirical question. Our data are consistent, however, with recent research by Mischel and Peake (1982), which strongly questions the predictive utility of the trait based cross-situational consistency approach. Mischel and Peake (1982) report that both in D. Bern and Allen's (1974) original study and in their own replication of that study that people who report high self consistency on a trait do not show greater cross-situational consistency in behavior than those people who report low consistency. (They do, however, evoke greater consistency in other people's descriptions of 578 P. BURKE, R. KRAUT, AND R. DWORKIN their behavior.) Consistency models empirically related to traditional trait models have not been proven to provide any great enhancement in behavioral predictability beyond a simple trait level model. and as measured will enable personality prospectors to extract the different insights of each or persuade them to seek, ultimately, an entirely new stream in which to pan. References Conclusions In the aftermath of Mischel's critique of the trait approach to personality, personality theorists adopted two responses. One was to emphasize an interactionist approach to personality (e.g., Magnusson & Endler, 1977), and the other was to explore other models of personality; the cross-situational consistency model and the self-schema model. We have shown that at least operationally, neither of these models is distinguishable from the traditional trait model it was designed to supplement or replace. We have shown that measures of self-schema and of cross-situational consistency correlate as highly with overall trait level as they do among themselves. In addition, we have argued that the concept of trait level (and the different experiences that go with different trait levels) can account for the evidence about individual differences in the speed, confidence, and richness of selfdescriptions, without appeal to schema. And, similarly, we argued that trait level may account for whatever predictive utility trait based cross-situational consistency models can claim. As yet, neither self-schema models nor cross-situational models have led to a strong predictive theory of personality. Our data suggest that these models are not, in practice, as innovative as once hoped. We concur with Mischel and Peake who state the pursuit of person-situation interaction will require a theoretical reconceptualization of both personality and situation constructs themselves, not just more clever methods for applying everyday trait terms to people's behavior in particular contexts. (1982, p. 748) As self-schema theorists take their cognitive process model from the laboratory and attempt to form a predictive personality model in the social world, they too may find that dependence on the trait model has undermined their endeavor from the beginning. Only a thorough evaluation of the relations between schema, cross-situational consistency, and traditional trait models both in theory Bern, D., & Allen, A. (1974). On predicting some of the people some of the time: The search for cross-situational consistencies in behavior. Psychological Review, 81. 506-520. Bern, S. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex-typing. Psychological Review. 88, 354364. Bern, S. (1982). Gender-schema theory and self-schema theory compared: A comment on Markus, Crane, Bernstein, and Siladis, "Self-schema and gender." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43. 11921194. Epstein, S. (1979). The stability of behavior I. On predicting most of the people much of the time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 10971126. Girvin, B. (1978). The nature of being schematic: Sexrole, self-schemas and differential processing of masculine andfeminine information. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Goldberg, L. R. (1963). A model of item ambiguity in personality assessment Educational and Psychological Measurement, 23, 467-492. Gough, H. G. (1969). Manual for the California Personality Inventory (rev. ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Jackson, D. N., & Helmes, E. (1979). Personality structure and the circumplex. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37, 2278-2285. Jackson, D. N., & Paunonen, S. V. (1980). Personality structure and assessment Annual Review of Psychology. 31. 503-551. Kenrick, D. T., & Braver, S. L. (1982). Personality: Idiographic and nomothetic! A rejoinder. Psychological Review, 89, 182-186. Kenrick, D. T, & Stringfield, D. O. (1980). Personality traits and the eye of the beholder Crossing some traditional philosophical boundaries in the search for consistency in all of the people. Psychological Review, 27, 88-104. Kuncel, R. B. (1973). Response processes and relative location of subject and item. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33, 545-563. Magnusson, D., & Endler, N. (1977). Interactional psychology: Present status and future prospects. In D. Magnusson & N. Endler (Eds.), (pp. 3-36). Personality at the Crossroads: Current issues in interactional psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Eribaum. Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing of information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 63-78. Markus, H., Crane, M., Bernstein, S., & Siladi, M. (1982). Self-schemas and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 38-50. McGuire, W., & Padawer-Singer, A. (1976). Trait salience in the spontaneous self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33. 743-754. TRAITS, CONSISTENCY. AND SELF-SCHEMATA Mischd, W. (1968). Personality and Assessment. New York: WUey. Mischel, W., & Peake, P. R. (1982). Beyond deja vu in the search for cross-shuational consistency. Psychological Review, 89, 730-755. Moskowitz, D. S. (1982). Coherence and cross-situational generality: A new analysis of old problems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43. 754-768. Peterson, D. R. (1965). Scope and generality of verbally defined personality factors. Psychological Review. 72. 48-89. Peterson, D. R. (1968). The clinical study of social behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Rogers, T. B. (1971). The process of responding to personality items: Some issues, a theory, and some research. Multivariate Behavior Research Monograph. 6. Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1979). Symbolic distance and congniity effects for pairedcomparisons judgments of degree of self reference. Journal of Research in Personality, 13, 433-449. 579 Rushton, J. P., Jackson, p . N., & Paunonea, & V. (1981). Personality: Nomothctic or idiographic? A response to Kenrick and Stringfidd. Psychological Review, 88, 582-589. Stones, M., & Burt, G. (1978). Quasi-statistical inference in rating behavior. 1. Preliminary investigations. Journal of Research in Personality. 13. 381-389. Vernon, P. E. (1964). Personality assessment: A critical survey New York: WUey. Voyce, C. D., & Jackson, D. N. (1977). An evaluation of a threshold theory for personality assessment Educational and Psychological Measuement, 37. 383-408. Zanna, M. P., Olson, J. M.. & Fazio, R. H. (1980). Attitude-behavior consistency: An individual difference perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 432-440. Received January 4, 1983 Revision received May 6, 1983