Primary Activities: Agriculture, Fishing, and Forestry

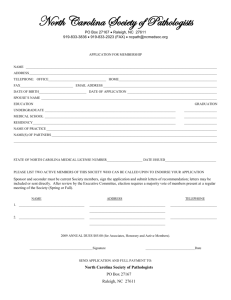

advertisement