Britain's Trade Competitors - Economic and Political Weekly

advertisement

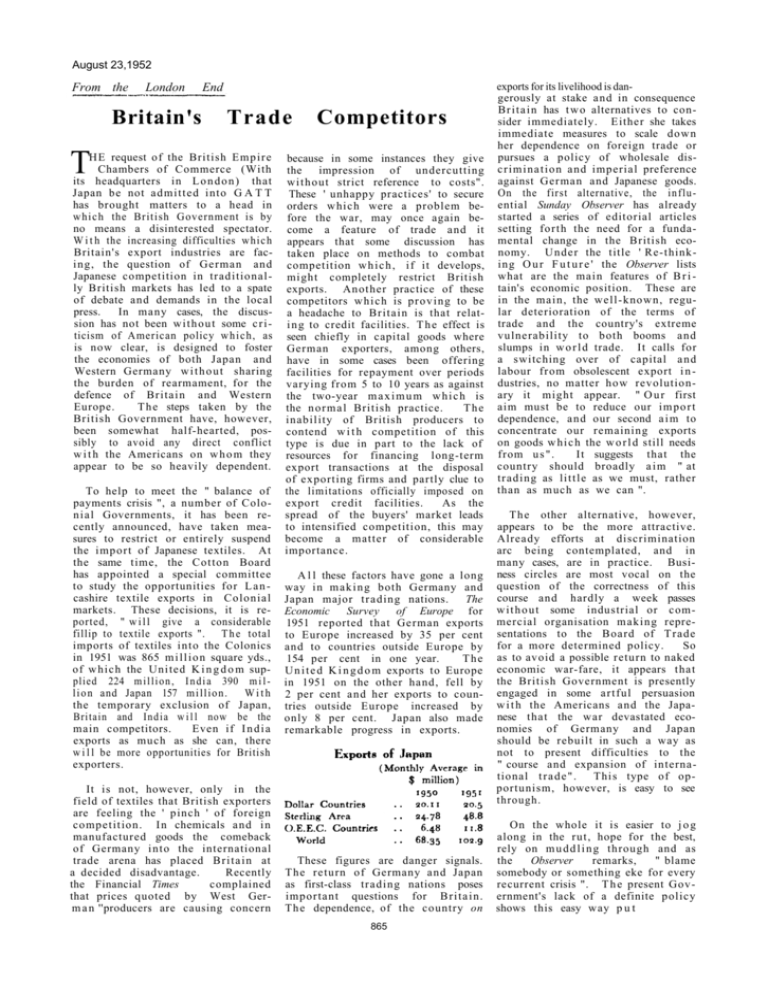

August 23,1952 From the London Britain's End Trade T HE request of the British Empire Chambers of Commerce (With its headquarters in L o n d o n ) that Japan be not admitted into G A T T has brought matters to a head in which the British Government is by no means a disinterested spectator. W i t h the increasing difficulties which Britain's export industries are facing, the question of German and Japanese competition in traditionally British markets has led to a spate of debate and demands in the local press. In many cases, the discussion has not been w i t h o u t some criticism of American policy which, as is now clear, is designed to foster the economies of both Japan and Western Germany w i t h o u t sharing the burden of rearmament, for the defence of Britain and Western Europe. T h e steps taken by the British Government have, however, been somewhat half-hearted, possibly to avoid any direct conflict w i t h the Americans on w h o m they appear to be so heavily dependent. To help to meet the " balance of payments crisis ", a number of Colonial Governments, it has been recently announced, have taken measures to restrict or entirely suspend the import of Japanese textiles. At the same time, the Cotton Board has appointed a special committee to study the opportunities for L a n cashire textile exports in Colonial markets. These decisions, it is reported, " w i l l give a considerable fillip to textile exports ". T h e total imports of textiles into the Colonics in 1951 was 865 m i l l i o n square yds., of which the United K i n g d o m supplied 224 m i l l i o n , I n d i a 390 m i l l i o n and Japan 157 million. W i t h the temporary exclusion of Japan, Britain and India w i l l now be the main competitors. Even if I n d i a exports as much as she can, there w i l l be more opportunities for British exporters. It is not, however, only in the field of textiles that British exporters are feeling the ' pinch ' of foreign competition. I n chemicals and i n manufactured goods the comeback of Germany into the international trade arena has placed B r i t a i n at a decided disadvantage. Recently the Financial Times complained that prices quoted by West Germ a n ''producers are causing concern Competitors because in some instances they give the impression of undercutting without strict reference to costs". These ' unhappy practices' to secure orders which were a problem before the war, may once again become a feature of trade and it appears that some discussion has taken place on methods to combat competition w h i c h , if it develops, might completely restrict British exports. Another practice of these competitors w h i c h is proving to be a headache to Britain is that relati n g to credit facilities. T h e effect is seen chiefly in capital goods where German exporters, among others, have in some cases been offering facilities for repayment over periods varying from 5 to 10 years as against the two-year m a x i m u m w h i c h is the normal British practice. The inability of British producers to contend w i t h competition of this type is due in part to the lack of resources for financing long-term export transactions at the disposal of exporting firms and partly clue to the limitations officially imposed on export credit facilities. As the spread of the buyers' market leads to intensified competition, this may become a matter of considerable importance. A l l these factors have gone a long way in m a k i n g both Germany and Japan major trading nations. The Economic Survey of Europe for 1951 reported that German exports to Europe increased by 35 per cent and to countries outside Europe by 154 per cent in one year. The U n i t e d K i n g d o m exports to Europe in 1951 on the other hand, fell by 2 per cent and her exports to countries outside Europe increased by only 8 per cent. Japan also made remarkable progress in exports. These figures are danger signals. The return of Germany and Japan as first-class trading nations poses important questions for B r i t a i n . The dependence, of the country on 865 exports for its livelihood is dangerously at stake and in consequence B r i t a i n has t w o alternatives to consider immediately. Either she takes immediate measures to scale down her dependence on foreign trade or pursues a policy of wholesale discrimination and imperial preference against German and Japanese goods. On the first alternative, the influential Sunday Observer has already started a series of editorial articles setting forth the need for a fundamental change in the British economy. Under the title ' Re-thinking O u r F u t u r e ' the Observer lists what are the main features of B r i tain's economic position. These are in the main, the well-known, regular deterioration of the terms of trade and the country's extreme vulnerability to both booms and slumps in w o r l d trade. It calls for a switching over of capital and labour from obsolescent export i n dustries, no matter how revolutionary it might appear. " O u r first aim must be to reduce our i m p o r t dependence, and our second a i m to concentrate our remaining exports on goods w h i c h the w o r l d still needs from u s " . It suggests that the country should broadly a i m " at trading as little as we must, rather than as much as we can ". The other alternative, however, appears to be the more attractive. Already efforts at discrimination arc being contemplated, and in many cases, are in practice. Business circles are most vocal on the question of the correctness of this course and hardly a week passes w i t h o u t some industrial or commercial organisation making representations to the Board of Trade for a more determined policy. So as to avoid a possible return to naked economic war-fare, it appears that the British Government is presently engaged in some artful persuasion w i t h the Americans and the Japanese that the war devastated economies of Germany and Japan should be rebuilt in such a way as not to present difficulties to the " course and expansion of international t r a d e " . This type of opportunism, however, is easy to see through. On the whole it is easier to j o g along in the rut, hope for the best, rely on m u d d l i n g through and as the Observer remarks, " blame somebody or something eke for every recurrent crisis ". T h e present Government's lack of a definite policy shows this easy way p u t