BSMC : is there room for me? : an exploration of nursing leadership

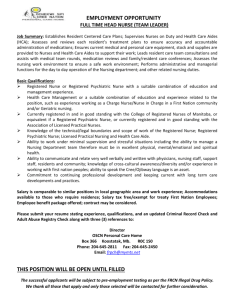

advertisement