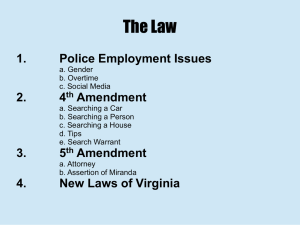

Katz in the Age of Hudson v. Michigan: Some Thoughts on

advertisement