Weeks v. United States: Exclusionary Rule & 4th Amendment

advertisement

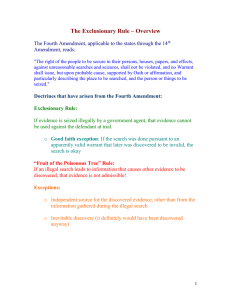

WEEKS v. UNITED STATES Case Basics Docket No. 461 Petitioner: Weeks Respondent: United States Decided By: White Court (1912-1914) Argued: Tuesday, December 2, 1913 Decided: Tuesday, February 24, 1914 Facts of the Case Police entered the home of Fremont Weeks and seized papers which were used to convict him of transporting lottery tickets through the mail. This was done without a search warrant. Weeks took action against the police and petitioned for the return of his private possessions. Question Did the search and seizure of Weeks' home violate the Fourth Amendment? Conclusion In a unanimous decision, the Court held that the seizure of items from Weeks' residence directly violated his constitutional rights. The Court also held that the government's refusal to return Weeks' possessions violated the Fourth Amendment. To allow private documents to be seized and then held as evidence against citizens would have meant that the protection of the Fourth Amendment declaring the right to be secure against such searches and seizures would be of no value whatsoever. This was the first application of what eventually became known as the "exclusionary rule." The Fourth Amendment and the "Exclusionary Rule" For the more than 100 years after its ratification, the Fourth Amendment was of little value to criminal defendants because evidence seized by law enforcement in violation of the warrant or reasonableness requirements was still admissible during the defendant's prosecution. The Supreme Court dramatically changed Fourth Amendment jurisprudence when it handed down its decision in Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914). Weeks involved the appeal of a defendant who had been convicted based on evidence that had been seized by a federal agent without a warrant or other constitutional justification. The Supreme Court reversed the defendant's conviction, thereby creating what is known as the "exclusionary rule." In Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961), the Supreme Court made the exclusionary rule applicable to the states. Designed to deter police misconduct, the exclusionary rule enables courts to exclude incriminating evidence from introduction at trial upon proof that the evidence was procured in contravention of a constitutional provision. The rule allows defendants to challenge the admissibility of evidence by bringing a pre-trial motion to suppress the evidence. If the court allows the evidence to be introduced at trial and the jury votes to convict, the defendant can challenge the propriety of the trial court's decision denying the motion to suppress on appeal. If the defendant succeeds on appeal, however, the Supreme Court has ruled that double jeopardy principles do not bar retrial of the defendant because the trial court's error did not go to the question of guilt or innocence (see Lockhart v. Nelson, 488 U.S. 33 [1988]). Nonetheless, obtaining a conviction in the second trial would be significantly more difficult if the evidence suppressed by the exclusionary rule is important to the prosecution. A companion to the exclusionary rule is the "fruit of the poisonous tree" doctrine. Under this doctrine, a court may exclude from trial not only evidence that itself was seized in violation of the Constitution but also any other evidence that is derived from an illegal search. For example, suppose a defendant is arrested for kidnapping and later confesses to the crime. If a court subsequently declares that the arrest was unconstitutional, the confession will also be deemed tainted and ruled inadmissible at any prosecution of the defendant on the kidnapping charge.