Review_20_3_2011_Sep..

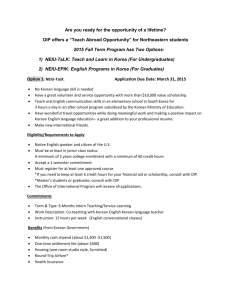

advertisement