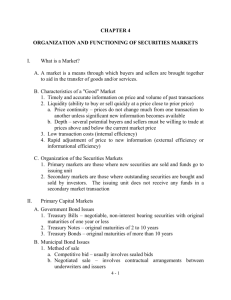

Market Organization and Structure Larry Harris Los Angeles, U.S.A.

advertisement