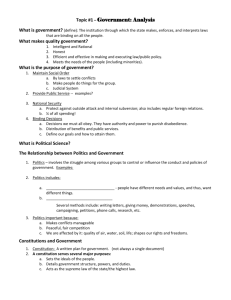

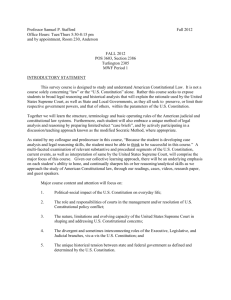

state constitutional interpretation and methodology

advertisement